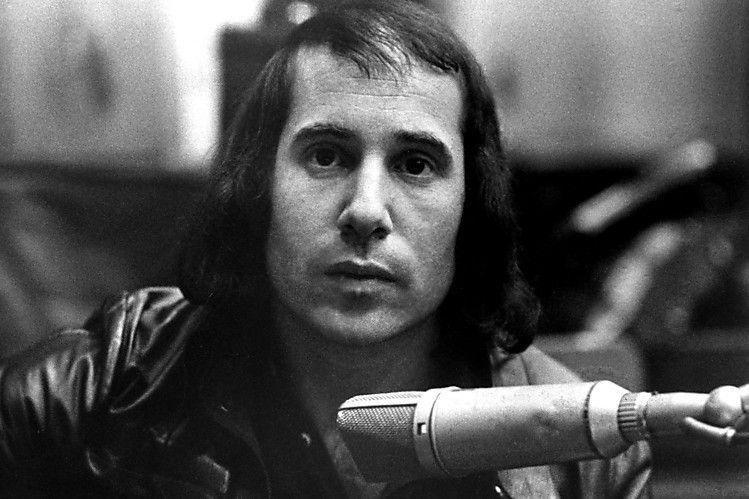

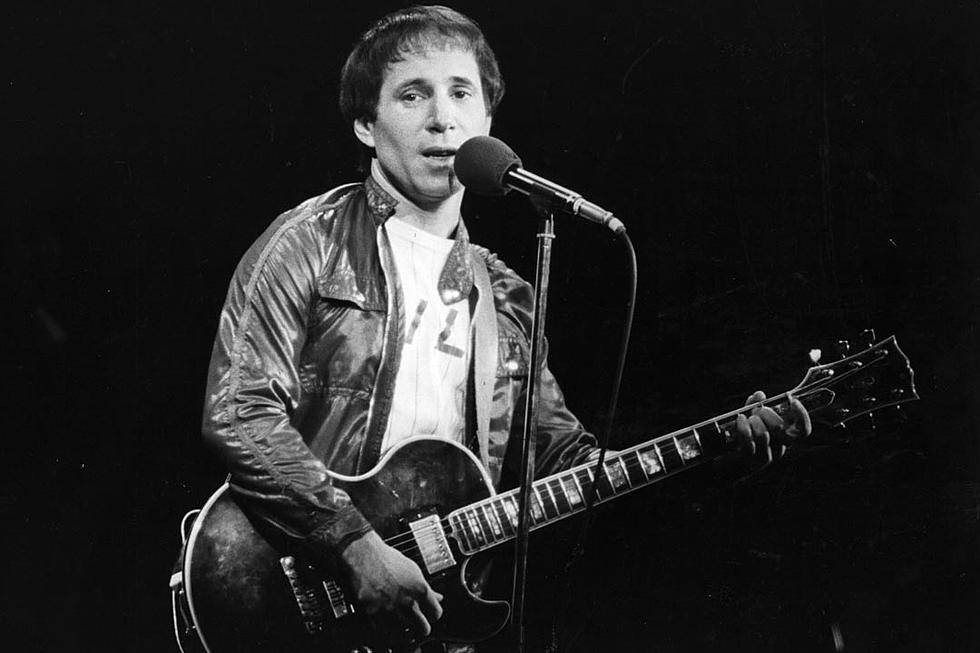

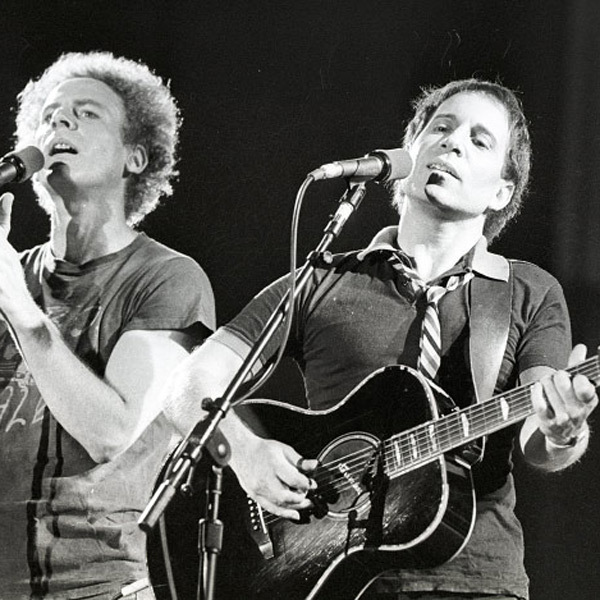

“I remember during a photo session at Big Records,” Paul recalled, back when he was Jerry Landis and Art was Tom Graph. “Something happened and Artie said, ‘No matter what happens, I'll always be taller than you.’ Did that hurt? I guess it hurt enough for me to remember sixty years later. But even during Simon & Garfunkel, I realised that people thought Artie wrote the songs and I finally asked someone, ‘Why do you think he wrote the songs?’ and they said, ‘Because he looks like he wrote the songs.’ Or, in other words, ‘You don't.’”

“It came up all the time. There is a prejudice against small men and that has been a problem at times because I happen to be a sort of alpha-male-ish type guy. It becomes a competitive thing. There's this attitude that ‘I'm taller so I could beat you up’ or ‘I should be in charge.’ Eventually, somewhere in my 30s or 40s probably, I told myself, ‘Listen, man, if you're going to make a big issue out of what you don't have, you're taking your actual gifts for granted.’ So I said, ‘That's the hand I've been dealt. That's the way I'm going to play it.’”

“I'd pretend God would come to me and say, ‘If you could be 6’2’’ with a mop of hair, would you pay $1 million?’ I said, ‘Absolutely.’ Then God said, ‘Would you pay $5 million?’ and again, I said, ‘Absolutely.’ Then the question changed: ‘If you could be 6’2’’ with a mop of hair, would you give away ten of your songs?’ and that's when I said, ‘No.’ That was too much. The songs are really a part of you. Not all of you, but kind of the best part of you. It's not the vain part of me or the pissed-off part of me—it's the generous part.”

— Chapter IV —

Crossroads & Parallels

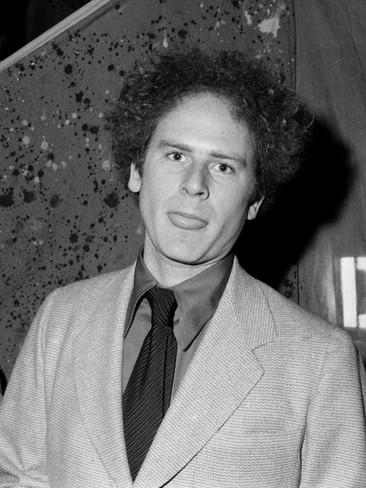

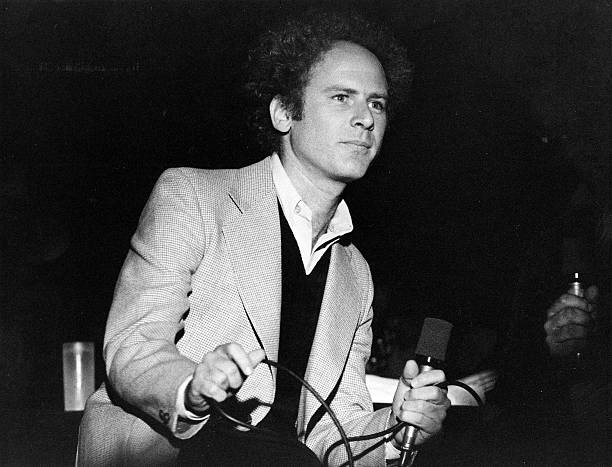

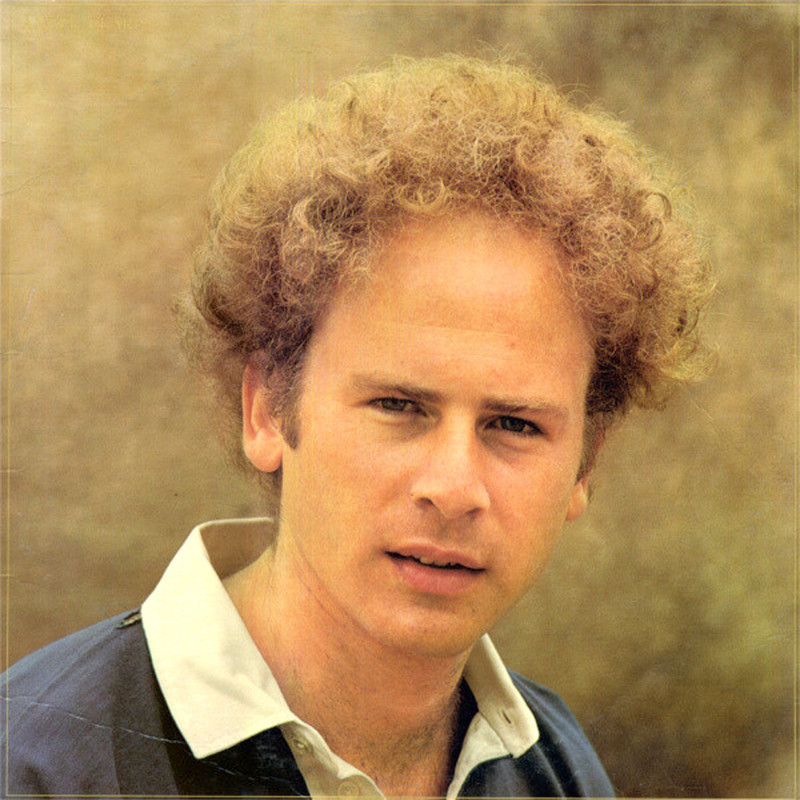

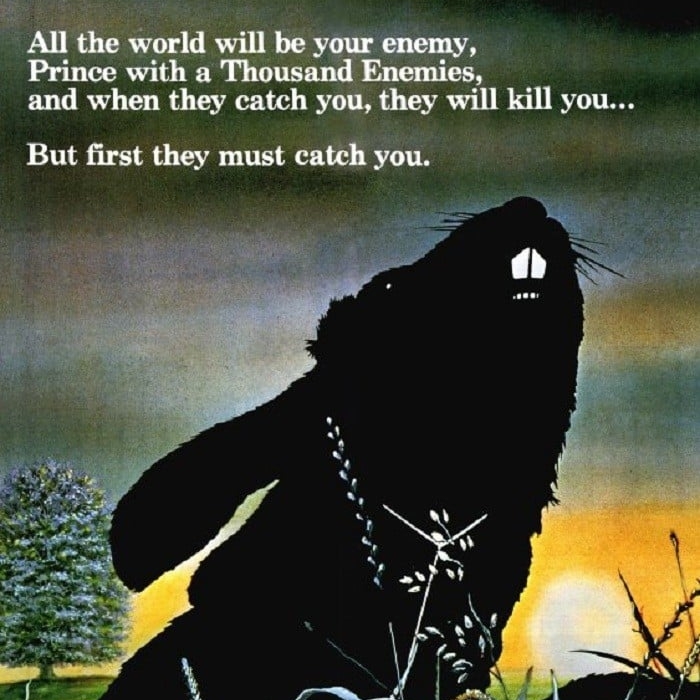

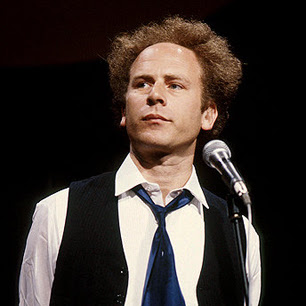

“Can you imagine girls writing love letters to someone called ‘Garfunkel’?” He had a voice gentle but powerful, like a waterfall, and golden locks growing ever-longer from his nordic head. He stood an inch shy of the male American average but, with his lanky frame, he always appeared taller, especially given the cultural memory of him towering over his partner on an empty stage.

His eyes—a cloudy blue—hid beneath a furrowed brow everywhere but under the limelights. Here, and often with a slouch or a sway, his body would enter stasis as his soul ascended to fill the room, escaping from the crown of his head like electric qi uncorked from his seventh chakra. It was in performance that Art found confidence; where he was a head above all.

As celebrity and fame consumed his daily life, performance became a full-time job. Singing was part of a persona more so than it was a release or a passion; it was what elevated him from mortal man to demigod. There was power in his voice — enough to make a storm listen, or a tyrant cry, or an audience forget who and where they were. Power enough to make a gifted bard dependent on him, though he was equally dependent on the bard.

The gnomish songwriter had a unique sound but a quiet voice, and the clout of Art’s countertenor stood ever the amplifier for whatever message or melody Paul wanted to preach. On its own, Art’s voice stood just as strong, and he stood straight-backed. Pride empowered him. Grammy dreams became Oscar dreams. Some called him a “sex symbol,” which I can only imagine was owed to his quiet confidence, his air of intellectualism, and his vocal prowess, atop the bohemian aesthetic he kept current, and his forays in Hollywood.

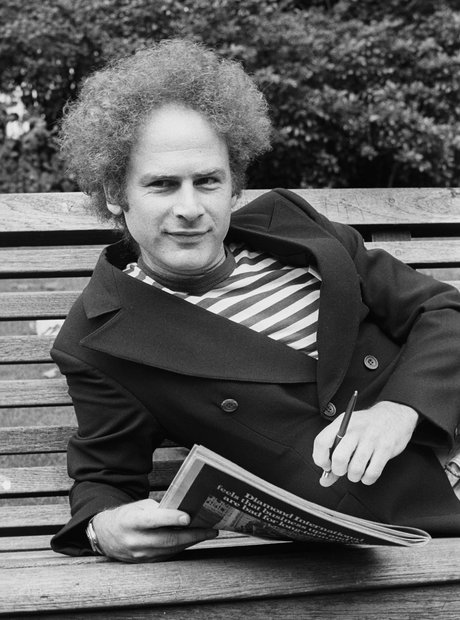

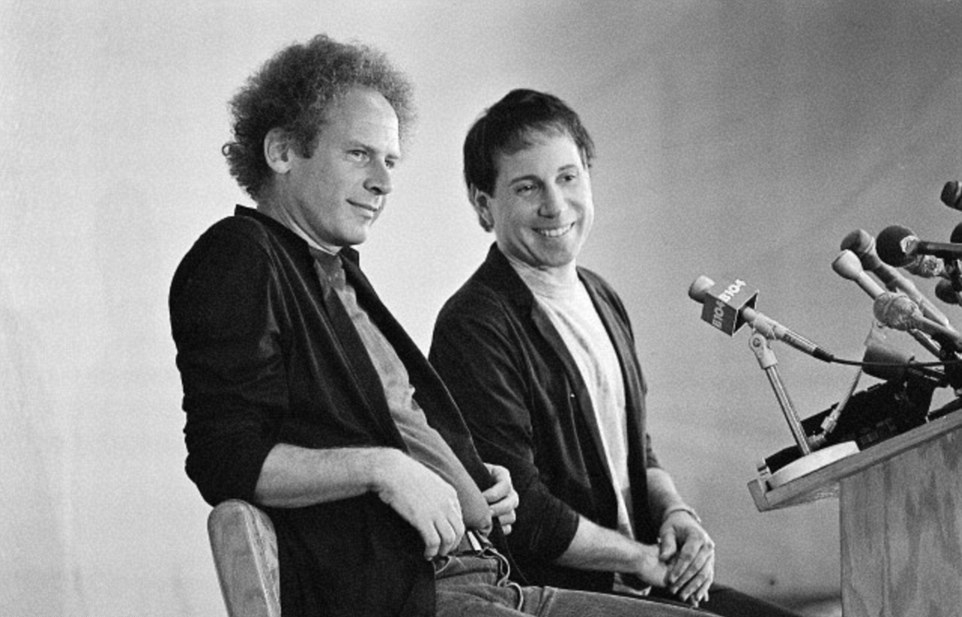

In a 2015 interview with The Telegraph, Art Garfunkel claimed his former partner suffers from a ‘Napoleon complex’—a derogatory characterization of “aggressive or domineering behavior, claimed to be a form of psychological compensation for one's short physical stature.” He said he had initially befriended Paul out of pity, “because he felt sorry for him,” “and that compensation gesture has [since] created a monster.”

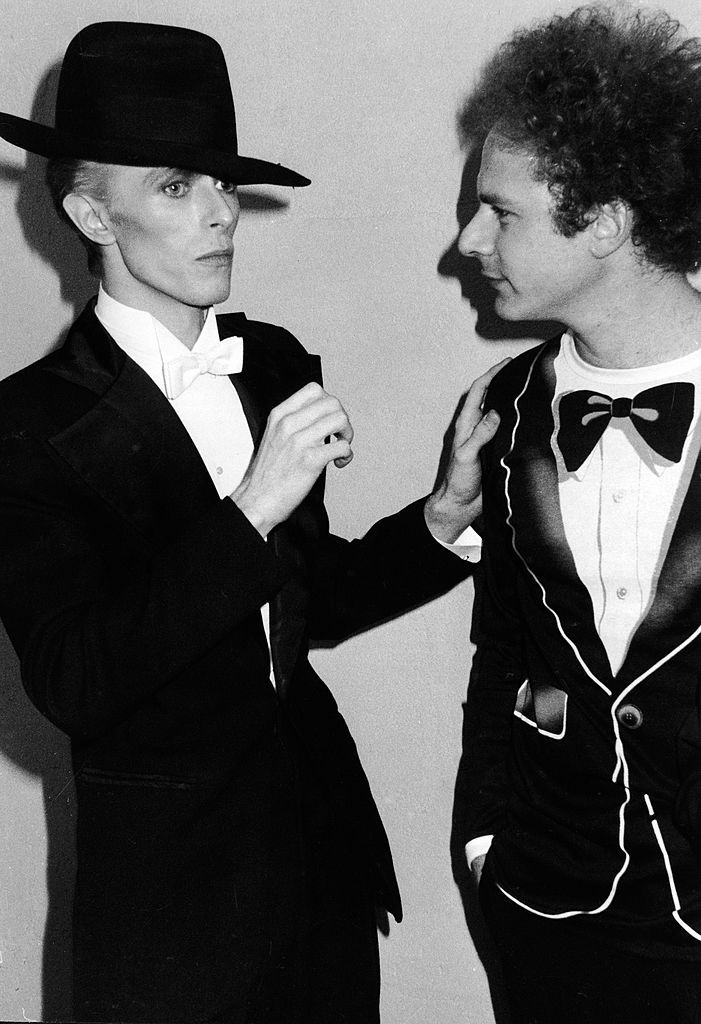

He recalled a moment in Hollywood that drew parallels between himself and George Harrison of The Beatles. “George came up to me at a party once and said, ‘My Paul is to me what your Paul is to you.’ He meant that psychologically they had the same effect on us. The Pauls sidelined us. And I’m tempted to get a little darker here because the word ‘suppression’ comes to mind. I think George felt suppressed by Paul [McCartney] and I think that’s what he saw with me and my Paul.”

Art has described his relationship with Paul as “fractious,” saying it had its faults yet still he regrets it ending. Nowadays he says he cannot fathom “why Paul wanted to” sever the partnership, considering they had just reached the peak of their fame. “It was very strange,” he said. “Not my choice. Nothing I would have done. I want to open-up about this. I don’t want to say any anti-Paul Simon things, and I love that the world still loves Simon & Garfunkel, but it seems very perverse to not enjoy the glory and walk away from it instead. Crazy. What I would have done is take a rest from Paul, because he was getting on my nerves. A rest was very much called for. The jokes had run dry. But a year of rest was all I needed.”

Art and Paul were equally proud of their abilities—Art with the angelic voice, and Paul with the gift of the bard—but under the weight of Paul’s creative vision and immense auteurist output, Art was stifled. It was 1970; he was getting older. He had many interests aside from music, and being pigeonholed into this one role—on top of having little authority in how he performed this role—left him dissatisfied and claustrophobic. He was boiling towards rebellion.

Ego in the Freudian sense was giving way to ego in the behavioral sense. Art was forging his own identity, seeking recognition from the world in places other than Paul's shadow. There were words he wanted to write, sounds he wanted to sing, and characters he wanted to interpret. There was much to life, he would discover, beyond arguing with friends and dissolving into a purple haze.

Paul may have been devoted wholly to the music industry, but Art always saw it as one of many options. He had never committed outright to being a musician—not as Tom Graph, not as Artie Garr, and not as Simon & Garfunkel—and even now, at the height and their fame, there was more foliage in reach than just the one branch. There was a whole forest to explore.

There were assuredly future acting performances, and he could host his own stage shows with his own songs—songs of his voice alone—and projects with no creative juggernaut to squabble with; to plead his case to; to undermine him. In the past few years, while Paul was struggling with writing and producing their songbooks—becoming depressed and aggravated in the process—Art was diving deeply inward, reading philosophy (Rousseau was his favorite) and practicing self-reflection and focus.

With his vast scope of interests, he imagined himself a renaissance man. Acting was proving this belief correct, and it was the ammunition he needed to rise against Paul’s singular vision. Art was, as he’d soon assert, a narcissist in utero.

Researchers at the University of Southampton have recently found the practice of meditation to be in correlation with an increase of narcissism. The intention of meditation, ironically, is for the opposite effect: a distancing from individual desires and biases, toward eschewing the self for the world. However, as Buddhist Lewis Richmond once wrote, “The act of sitting in silence—eyes closed or facing a wall; attention focused on the inner landscape of breath, body, and mental activity—could at least be characterized as self-absorbed.”

Psychologist William James argues that the practice of any skill increases an ego. In fact, while narcissists aren't inherently more advantaged or smarter than the average person, they do have one extra trait that helps them succeed: ‘mental toughness.’ Though they are “often full of themselves and difficult to deal with,” as Reuben Jackson writes, “they may be better suited to deal with adversity…”

According to Queen University's Dr. Papageorgiou, “People who score high on subclinical narcissism may be at an advantage…because their heightened sense of self-worth may mean they are more motivated, assertive, and successful…” His team of researchers found that those who scored high on subclinical narcissism indicators were more confident, which subsequently encourages better performance, “academically, professionally, and in other achievement-based settings.” “Being confident in your own abilities is one of the key signs of grandiose narcissism and is also at the core of ‘mental toughness.’”

Those with a high ‘mental toughness’ perceive challenges as opportunities, furthermore believing they have the social and mental ability required to overcome an obstacle and excel. These ‘confident narcissists’ also possess a great tenacity as a coping mechanism, turning rejection and failure into motivation rather than despair. Such confidence is innate, whereas the typical negative aspects of narcissism are “not inevitable;” “it’s possible for people to lead high power careers and full lives without falling into a pattern of narcissism.”

This was not the case for Art Garfunkel. As the years passed, he honed and diversified his skills; he perfected his pitch, and was praised for it; and he gained access to the inner circles of the American elite, to become broadcast and beloved on televisions, radios, and newsstands across the Western world. The confidence within him matured—into ego.

Remember: As a boy, surely, Art did not enjoy the limelight. “To be out—and involved—is not my natural state. When I was in high school, I withdrew a lot. My friends were reduced to one or two. I read a lot, and I played the game of ‘doing well in school’—maybe by default… I could never accept myself as ‘one of the gang.’ Everything I did was cast in the image and perspective of the outsider. I became a sociologist in spirit; an incessant observer.” According to Preston Ni MSBA, a Stanford fellow and Harvard grad working out of Silicon Valley, introverted narcissists “tend to observe (judgmentally) rather than act, and…yet, their quieter brand of superiority complex betrays itself through aloof detachment and disconcerting nonverbal cues.”

“When they do speak, their comments tend to be critical and judgmental, focusing on their own conceited views.” “One of the most common characteristics of an introverted narcissist is a sense of ‘withdrawn self-centeredness.’” “The self-perceptions of some introverted narcissists include notions such as: ‘I’m special,’ ‘I’m one-of a kind,’ ‘I’m ahead of my time.’” Such outwardly spoken beliefs are evident of perceived “superiority, grandiosity, and entitlement.” In thinking himself “exceptional,” Art Garfunkel (as with any introvert narcissist) “creates a reassuring role, submerging the fearful and vulnerable true self.” “To this extent, the aloofness and/or smugness serve as a defensive mechanism keeping people away, lest the narcissist is exposed for her or his interpersonal inadequacies.”

Art had been raised to be proud of himself since infancy, and he was always intelligent, curious, and confident. (No ten-year-old loner stands before his entire school and sings Enrico Caruso without confidence.) The outside pressures of youth, school, and one-hit wonderdom made Art more sure of himself, and he endured life's critics with his innate ‘mental toughness,’ which was cultivated—for better or for worse—by his friendship with Paul Simon.

Narcissists are ego-driven, and they’ll admit to it, which Art has frequently done, such as in his March 1982 interview with Rolling Stone. When journalist Neil McCormick first met Art, he described him as “a fascinating character,” noting, “For a non-songwriter, he talks with more care and eloquence than most lyricists [and he] is refreshingly unembarrassed about exposing his own ego. He says he recognized as a child that he had a special talent: ‘When I heard the radio I would think, ‘Who sings better than me? This is a gift!’’”

In the interview, Art wasted no time in expressing his belief that history has unfairly given Paul Simon most of the credit for the success of their double-act. Paul may have been a legendary songwriter, but “I gave him one of the all-time great voices,” he said. “I don’t know if they would have been hits without that.”

As a fan of Rousseau, Art Garfunkel was undoubtedly familiar with the concept of “amour-propre,” or “self-love based on the opinions of others.” He believed it to be unhealthy, suggesting that “arbitrary social comparison led to people wasting their lives trying to look and sound attractive to others,” as this New York Times article so delicately put. Journalist Arthur Brooks mused that, in our modern era, “Narcissus would fall in love with his own Instagram feed.”

The opposite of “amour-propre,” theorized eighteenth-century French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, is “amour de soi,” the “intrinsic well-being” that necessitates “being fully alive at this moment.” French for “love of self,” “amour de soi” is the philosophical concept of pursuing self-interest without the expense of others, and of being “concerned solely with regarding oneself as an absolute and valuable existence.”

As you'll come to learn, all of Art Garfunkel's obsessions—from walking across America to showboating in Japan; from reading Random House Dictionary to his infatuation with fatherhood—goes to prove his deep, confident, “amour de soi.”

“Catch-22” premiered in June 1970. Gary Arnold of the Washington Post said that, in his role as Lt. Nately, Art “embodies a kind of youthful sweetness” as an idealistic foil to the rest of the dark, manic characters. Though “Catch-22” didn't perform as well as Mike Nichols’ previous films, “The Graduate” and “Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” his next film had already been greenlit and was in production.

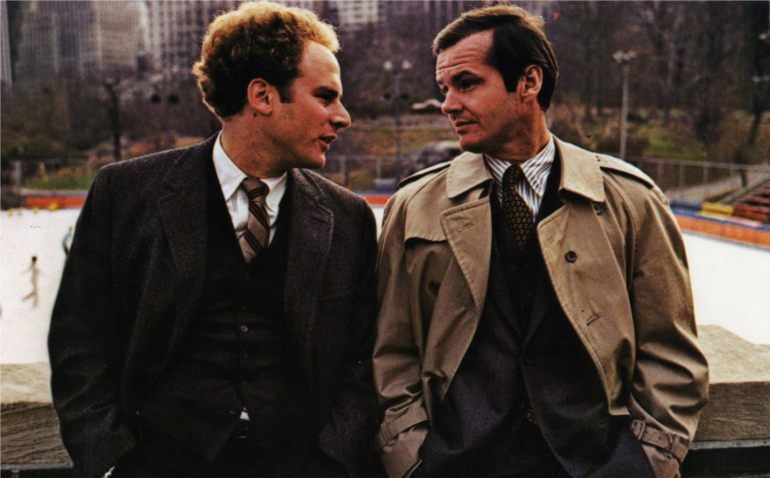

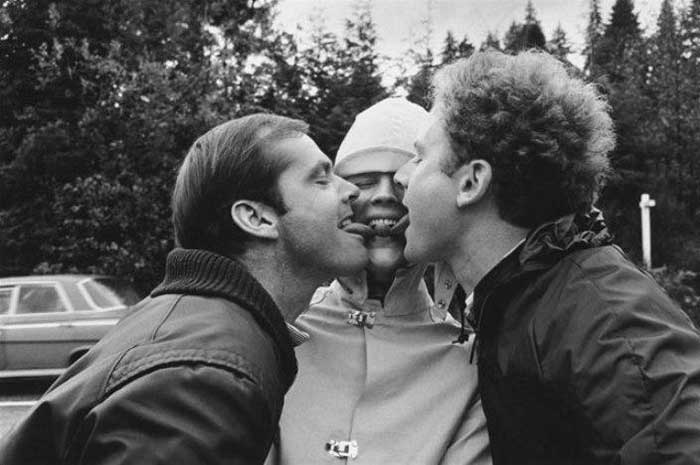

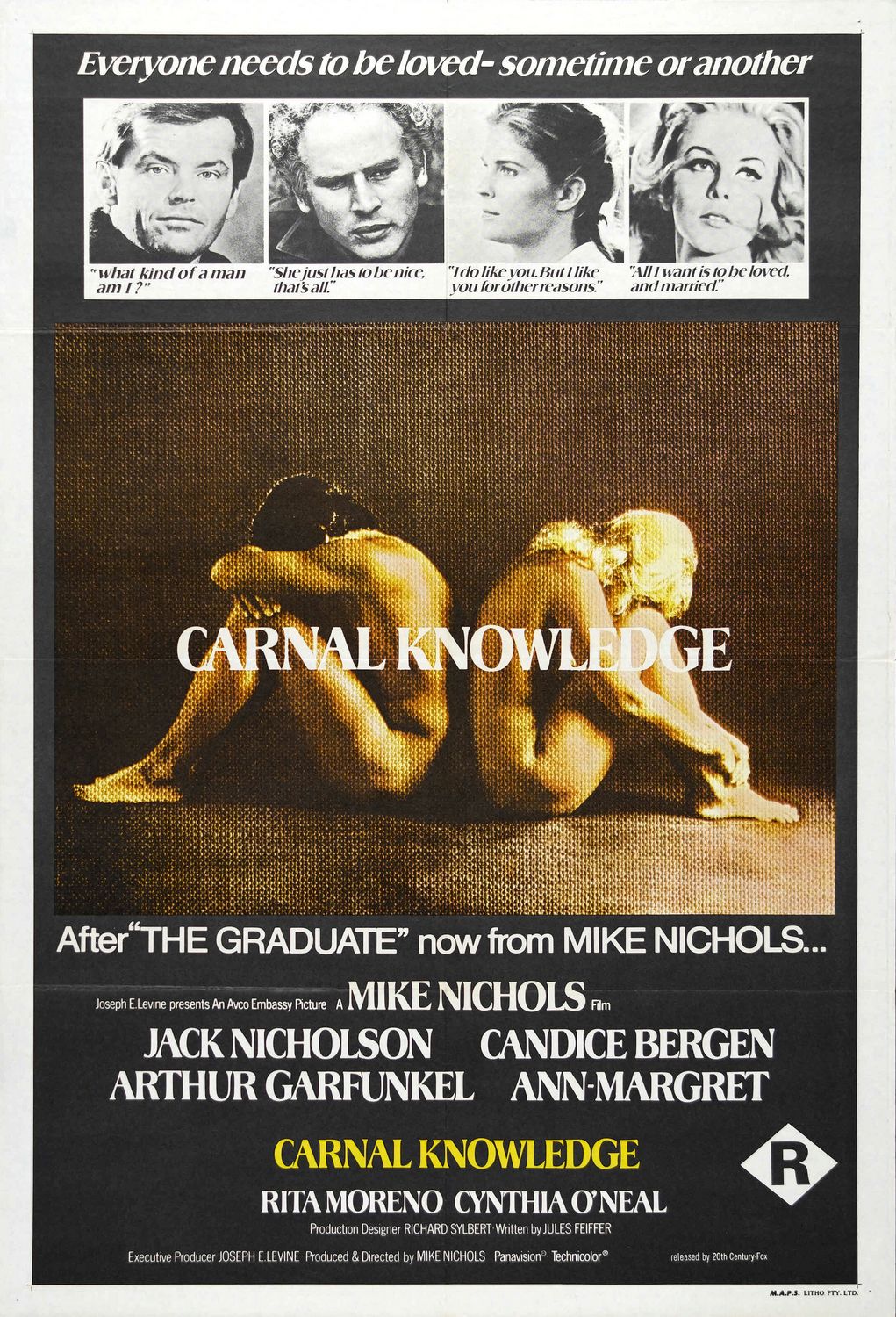

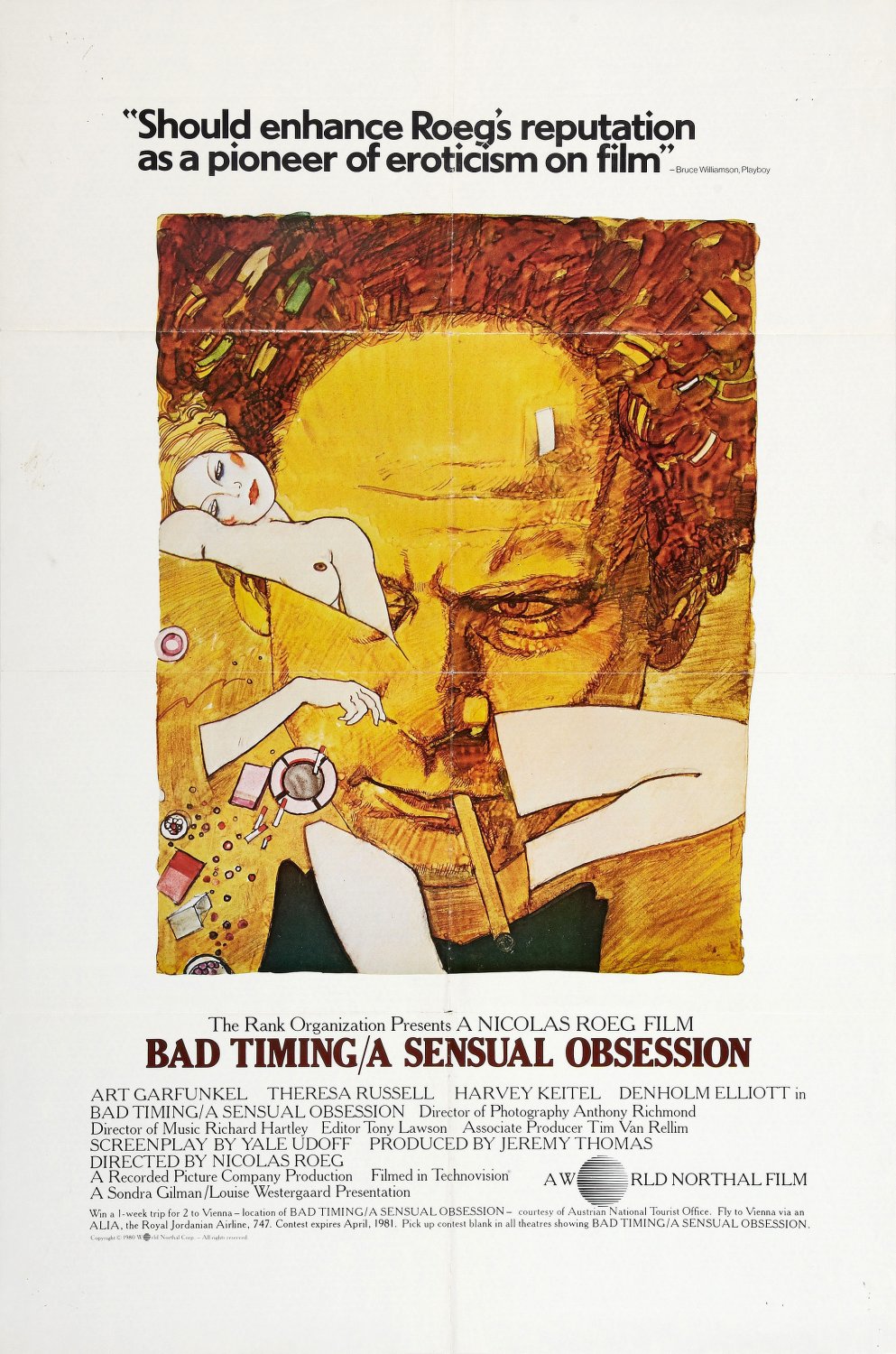

In the second half of 1970, Mike Nichols directed Art Garfunkel in “Carnal Knowledge,” opposite Jack Nicholson and alongside femmes Candice “Murphy Brown” Bergen and “The Sweet Swede” Ann-Margret. Art portrayed effeminate nice-guy ‘Sandy’ who marries the “virginal” Candice Bergen; consumed with guilt, she ends her affair with Sandy’s BFF, a smarmy Lothario played by Jack Nicholson. As Sandy’s marriage falls apart due to his high expectations, he begins to mimic the “promiscuous womanizing” of Jack’s misogynistic character, who, in turn, is giving monogamy a chance with the “gorgeous but emotionally-needy” Ann-Margret. It’s a whole to-do.

Originally written as a play, “Carnal Knowledge” was progressive for Hollywood in its liberal use of certain “four-letter words.” The vulgar and sexual nature of the film, while a definite and necessary moment in the New Hollywood movement, was not received well by communities that still upheld the morals and virtues of small-town Americana. On January 13, 1972, police in Albany, Georgia, raided a cinema and seized the reels of “Carnal Knowledge.” They convicted the cinema’s manager on the crime of “distributing obscene material.” The case went to the state Supreme Court, which agreed, and so the cinema’s manager took the case even higher.

The federal Supreme Court—the fairest hands in all the lands—ruled the State of Georgia had overstepped their bounds in deciding what is or is not “obscene,” given the film being a product of Hollywood that the cinema simply paid to play. In Jenkins v. Georgia, 418 U.S. 153 (1974), the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the conviction, saying, “Our own viewing of the film satisfies us that ‘Carnal Knowledge’ could not be found…to depict sexual conduct in a patently offensive way… While the subject matter of the picture is, in a broader sense, sex, and there are scenes in which sexual conduct including ‘ultimate sexual acts’ is to be understood to be taking place, the camera does not focus on the bodies of the actors at such times. There is no exhibition whatever of the actors' genitals—lewd or otherwise—during these scenes. There are occasional scenes of nudity, but nudity alone is not enough to make material legally obscene…” Which meant, in order to facilitate a ruling, nine old stoics—notably including Warren E. Burger, Thurgood Marshall, and William Rehnquist—had to watch the most salacious non-porno of the era—together—presumably while sharing a bowl of Orville Redenbacher and rubbing each others’ backs.

Meanwhile, movie critic Roger Ebert loved “Carnal Knowledge” so much he saw it twice. TIME Magazine wrote in its review, “Singer Art Garfunkel has become an authentic screen presence; one of the few American actors who can portray naiveté.” This role earned him a Golden Globe nomination for ‘Best Supporting Actor.’ (Unfortunately, even if he had won, nobody cares about the Golden Globes.) While working together on this film, Art formed a lifelong friendship with Jack Nicholson, wherein Jack fit the same niche Paul Simon once had: that of the gregarious and witty pug.

Jack Nicholson was the most notable Hollywood stanchion to rope Artie into the party scene. “We became buddies,” Art said of his time on set with Jack. “He’s not the frivolous man people think he is. But those were fun times and fame was a big kick. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise!”

Art loved the nightlife, and to this day he’ll defend his friend for their debauched romps and zesty all-nighters. “Jack’s not that wild. Jack is a fucking first-class artist; a brilliant artist who looks to do brilliant work with intelligent scripts—that’s Jack. Sure, he loves women. Why do we seek to become famous? We want the women. That’s what it’s about. He’s just a great, funny, New Jersey guy with a medieval code of honor, who is very loyal. We have a lot of mutual respect.”

In a 1973 interview with Rolling Stone, Art more-or-less agreed with those who’ve claimed he portrays himself in movies. “Well, you’re offered a script, you read it, and you recognize a large part of yourself in it. So you get into it, reject those parts of you that don’t relate to the character and take those parts that do, and try and make that all of you. If you’re cast well, it works.”

Art claimed Mike Nichols had intentionally chosen him to portray one of two BFFs in “Carnal Knowledge” due to his personal history with Paul Simon: growing-up with a close friend and slowly drifting apart. The interviewer asked him if he often thought of Paul while working opposite the similarly-potent Jack Nicholson. Art replied with deflection, saying, “Somewhat… I think Mike picked up on his knowledge of my friendship with Paul Simon as far as his choice of me in this role and why he thought I could play this half of a friendship. He knows certain things about us. He’d met Paul a few times. He was going to cast Paul in ‘Catch-22.’ He was going to be Dunbar. I was to be Natley and Paul was going to be Dunbar. But Buck Henry had too many characters, and one of the ones that was cut was Paul.”

After that, Paul felt “like there wasn’t enough candy to go around—and he was left out, I think. He would have enjoyed a gumdrop.”

Art had transitioned from ‘a subordinate relationship with Paul’ to ‘a subordinate relationship with Mike Nichols.’ The interviewer asked Art if he intentionally preferred to be “dependent on someone else’s creative instincts,” to which Art replied, “Yes. I operate from an underdog role—or, I have in the past, until now. That’s over. They’re very similar. I’d like to have been the one who had the freedom of obscurity; that sort of ‘behind the scenes’ a little bit. It’s worked for me [but] not anymore. No. Now I’ve tested myself with more power and I like it.”

He revealed to the interviewer that he had secretly loved the fame of the music industry while he was a boy, as Tom & Jerry, and later as half of Simon & Garfunkel. His desires for popularity and wealth factored “viscerally” into his career decisions, guided by crude base emotions. He had “some kind of gut feeling that making money is probably a smart thing to do… I never got that specific as to how far I wanted to take [the musician route] though.”

“You know, here’s how I think it works with a lot of people. A person may feel, ‘I don’t know that striving to build-up a bank account is a worthwhile endeavor, but it might be.’ And opportunities have come along that make me able, at this point—and only at this point—to satisfy that goal… If I should ever want that goal. While I am still not sure about what matters to me in life, and while this opportunity is temporal, it behooves me to relate to it and cover that base, lest I should someday feel, ‘Shit, money really makes life more comfortable…’ Pursuing a lot of money is a foolish waste, though. I have a very strange relationship to money. I don’t know how to spend it. I don’t really feel it leads to much happiness. I can’t develop a real interest in material goods. Money mostly means convenience for me, [i.e.] cabs. I like getting out of a movie if the movie is boring in the middle and not feeling I’ve wasted the rest of the money I spent.”

Paul had a similar upbringing, three blocks away from the Garfunkel family home, and yet he felt an ambiguity about financial success. “It’s hard to know [if it’s essential]. On a personal level, questions of the economy, unemployment—things like that—they’re not personal for me, so it becomes an abstract issue. Do I wish that, in general, the lot of poor people would be much improved? Yes, I do. That’s an abstraction… You can’t go your whole life and have—for me—an average amount of money. I came from a middle-class family; we weren’t poor, but I would have always had to keep working. I rode the subway to work. I took a bus.”

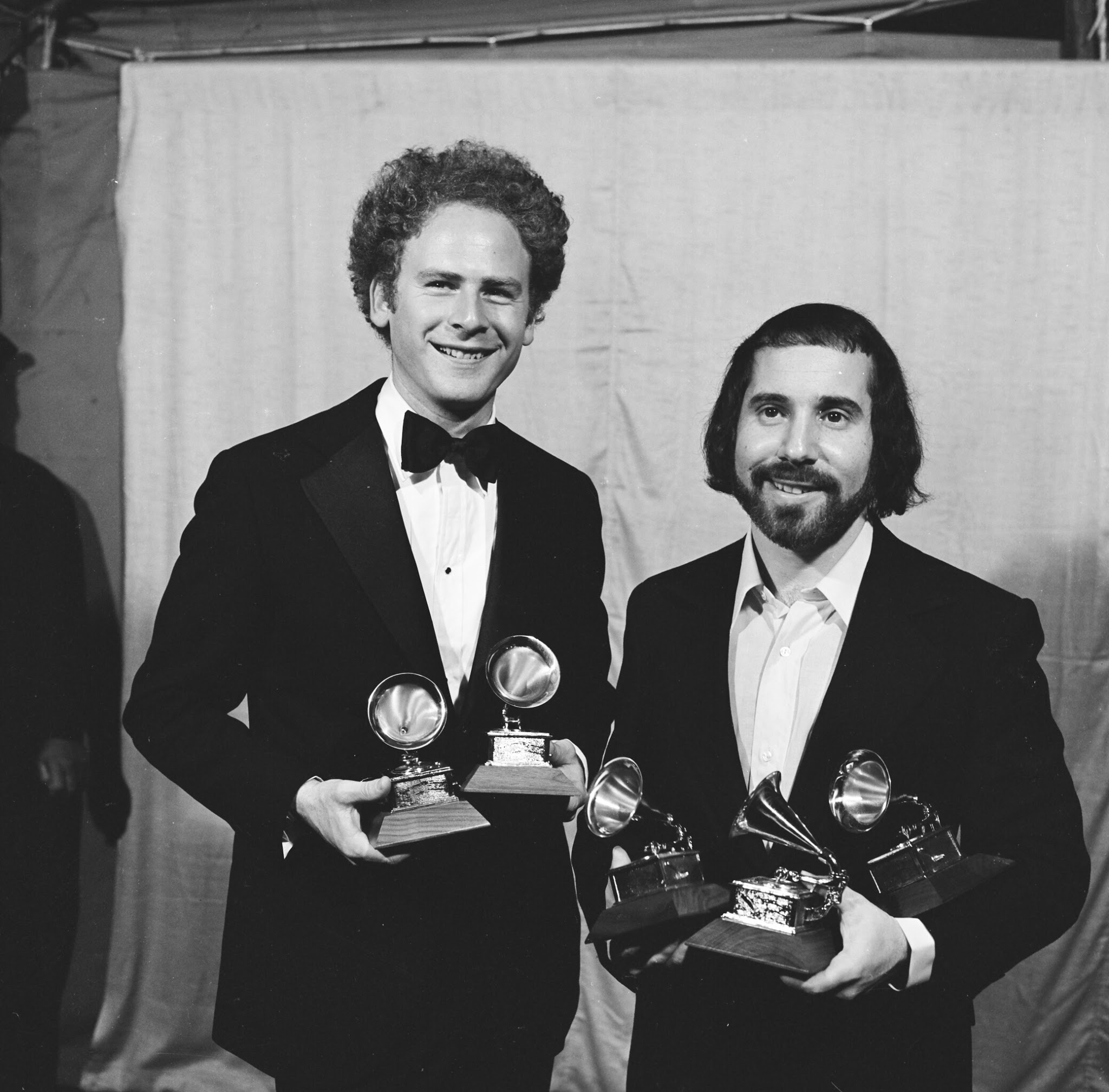

After the March 1971 landslide of Grammys earned by “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” Art Garfunkel took his then-girlfriend Linda Grossman on a long vacation to the Hebrides, an archipelago off the northwest coast of Scotland, where the Gaelic language reigns, the hedgehogs run rampant, and stones stand upright for longer than most civilizations. Norway-bound freighters traverse the cool, indecisive marshes that surround hillock mounds—populated and not—of grassy grazing fields and mighty basalt cliffs.

Freighter, incidentally, was often Art’s preferred mode of transport when touring Europe, aside from walking. “Freighter travel fit my sensibilities. The beauty of the sea; the romance of the stars; no passengers. I could break out of the 24-hour cycle and go on a fit of writing for forty hours.” In Europe, he visited the palaces of the baroque era, in Prague, Lübeck, and Belgrade, where he studied classical composers—namely, Bach—and learned to play the harpsichord.

In the autumn of 1971, Art Garfunkel accepted a position at Connecticut's elite Litchfield Academy. “I had come off of ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water.’ I craved normality. I was in a relationship, living in a country house I had bought… The school was nearby.” He became “Mr. Garfunkel,” teaching geometry to high school sophomores.

“We make weird left and right turns in our lives. You imagine that the country and not the city is where you want to be; that a cottage in the country might be good. I got in front of the kids and put geometry stuff on the blackboard and I would say, ‘Yeah, I’ve had ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water,’ but we’re not going to talk about that, we’re going to talk about geometry, and at the end of the year I’ll deal with the fame trip.’ And they were like, ‘He’s really talking geometry!’”

He colored himself “highly academic,” querying if he were “the most qualified man in pop.” “If the answer is no, who would be my second? It’s odd that I had hit records with this academia,” he boasted. “It’s weird how much homework I did.”

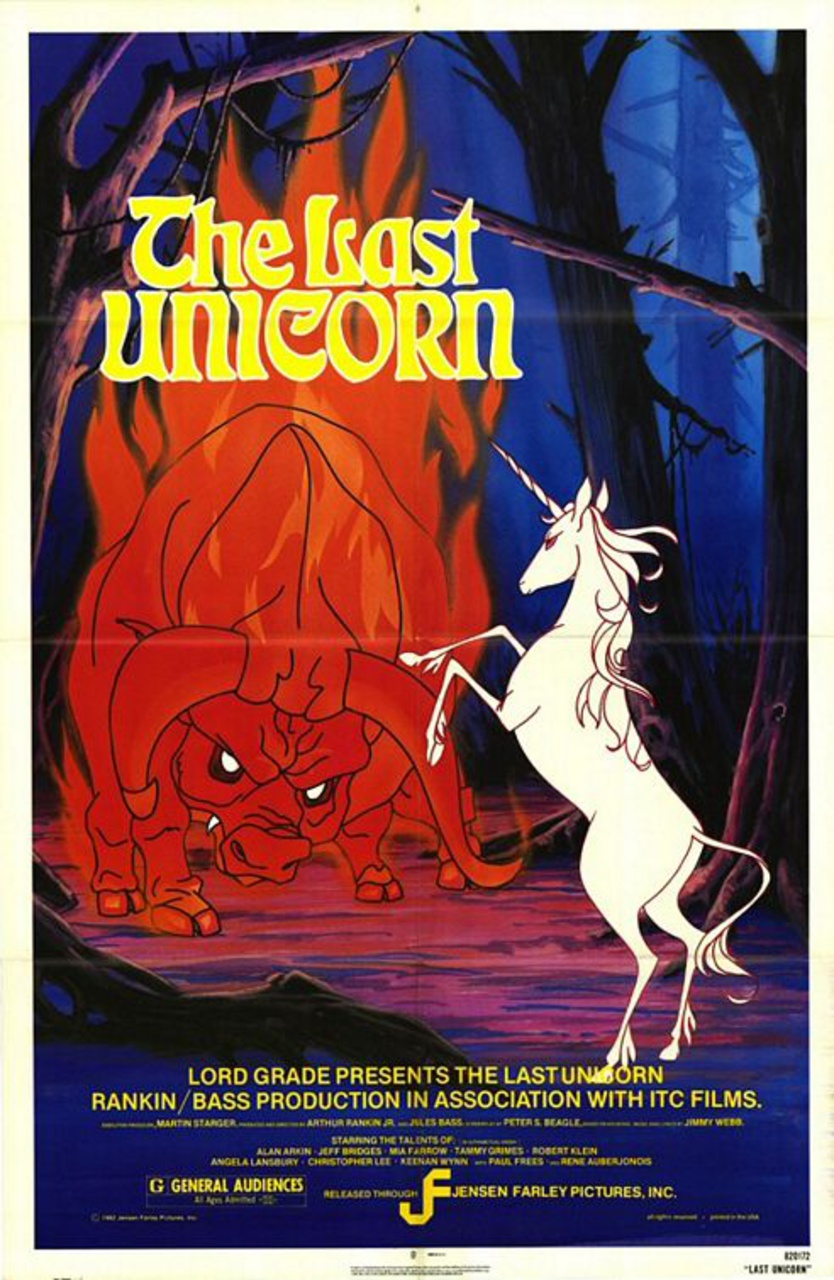

But normalcy was not satiating his ego, and teaching did not fill the hole in his heart, nor did it bring him recognition or pride. Having learned the classical style in the motherlands of classical style, Art fancied himself ready to compose a classical-inspired solo album. He met with Randy Newman and songwriter Jimmy Webb. He quit teaching and, for the next fourteen months, he lived in the studio, re-recording and fine-tuning every note of his first-ever independent creative endeavor.

Paul Simon, too, had gravitated towards teaching. In the summer of ‘71, he taught courses on songwriting to students at NYU Tisch. One of his wards, Melissa Manchester (soon to earn representation from Clive Davis and launch her own career), remembered Mr. Simon being a nervous but devoted teacher. After class, he'd listen to his prospective bardlings perform their original works, and he'd supply comments, critiques, and suggestions to help improve them. He often related his advice back to his own education—the dogged hunt and trial-by-fire of his youth, in Queens, London, and Columbia.

In January 1972, Paul released his eponymous solo album. There were few reviewers who didn't rave about its cultured sound and honest messages. It charted high in the US, reaching #1 in Japan and the UK. The hit lead single, “Mother and Child Reunion,” was inspired by the worldly rhythms of Jamaica, whereas the title was incidentally inspired by a restaurant menu.

“Know where the words came from on that? You never would have guessed. I was eating in a Chinese restaurant downtown. There was a dish called ‘Mother and Child Reunion.’ It’s chicken and eggs. And I said, ‘Oh, I love that title. I gotta use that one.’” This kernel sat in his head for a few weeks until, “last summer, we had a dog that was run over and killed—and we loved this dog. It was the first death I had ever experienced personally. Nobody in my family died [therefore] I felt this loss—one minute there, next minute gone—and then my first thought was, ‘Oh, man, what if that was Peggy? What if somebody like that died? Death—what is it? I can’t get it.’ And there were lyrics straight-out forward like that. ‘I can’t for the life of me remember a sadder day. I just can’t believe it's so.’ Those are the lyrics. The chorus for ‘Mother and Child Reunion,’ well, that’s out of the title. Somehow there was a connection between this death and Peggy and it was like Heaven. I don’t know what the connection was. Some emotional connection. It didn’t matter to me what it was. I just knew it was there.”

Other hits included “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard,” “Run That Body Down,” and “Congratulations,” the latter two of which reference his relationship with his wife, Peggy. Though he was devoted to her, as evident in “Mother and Child Reunion,” their marriage was going through a rough period owed to his distractions and absences. They would divorce in 1975. The dormant emotions behind this split can be felt in the performances he gave in the studio. Jon Landau of Rolling Stone called Paul’s eponymous album “his least-detached, most personal and painful piece of work thus far.”

Paul experimented with a dozen musical styles for the album, including jazz, blues, reggae, and Latin music — a taste many critics fondly called “eclectic.” “I like the other kinds of music,” Paul told Rolling Stone after the release of the album. “The amazing thing is that this country is so provincial. Americans know American music. You go to France—they know a lot of kinds of music. You go to Japan, and they know a lot of indigenous popular music. But Americans never get into the South American music. I fell into Los Incas—I loved it. It’s got nothing to do with our music, but I liked it anyway. The Jamaican thing—there’s nobody getting into a Jamaican thing. Jamaicans have a lot of good music, an awful lot.”

He flew to Kingston in order to record “Mother and Child Reunion” with a band that really understood the reggae style. However, once there, he realised he couldn’t simply hire them as instrumentalists — he had to let them create the sound organic, and he had to adapt himself to fit them. “I got that by making a mistake… I said, ‘I’m not going to get it out of the regular guys. I gotta get it out of the guys who know it.’ And I gotta go down there willing to change for them… I started to show them the song and play, and we started to work it out, and they were playing, and I would play… I’d sing the song, we’d write down the chords. Now we know the song. Now, I start to play the guitar—a rhythm guitar part, like I do on almost all the stuff—but it was bad. So I sat down and said, ‘You play it. Play what you want.’ That’s the key thing. Let them play whatever they want, and then you change. You go their way. That’s how you get that.”

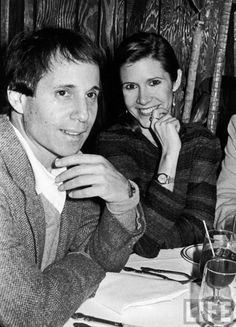

Jon Landau of Rolling Stone interviewed Paul Simon across three days in late May and early June, 1972, producing thirteen hours of record tape to be transcribed and published the following month. The two got to know each other well over these three days, with Landau later saying, “I found him open on virtually every subject, but always deliberate and intent on saying exactly what he meant… I realised he really did approach this interview the same way he approaches writing, recording, performing: as a perfectionist.”

Paul described his relationship with his former partner as “Cautious. We get along by observing certain rules. We’re aware [of what irritates each other]. We try not to do that.” When asked about their split—at this point, two years prior—Paul didn’t seem uncomfortable. “I find it a relief. It took me to a nice place. I can’t say it took me where I wanted to go, because I had no idea where I wanted to go, but…I could go and do what I wanted without being tense about succeeding or not succeeding. I’d already been successful. I mean, I knew I never could top the success of ‘Bridge.’ I’m not going to sell more than eight million records, so it’s kind of a nice place to be. So you start again, but actually you have nothing to lose. I’m also older than I was, so I don’t have that drive; I already had a few years of being successful.”

Those years may have been brief but the success he speaks of was a kind few achieve: donating more than a dozen songs to the annals of music history, to the memories of a generation, and to the cultural lexicon of generations to come. “Judging from the amount of recordings and the amount of airplay and the amount of that kind of measuring device, the most popular songs of mine are ‘Sound of Silence,’ ‘Mrs. Robinson,’ ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water,’ ‘Feeling Groovy,’ and—a song that’s not mine, but is associated with us—‘Scarborough Fair.’ That song’s alive still. You hear it still, and those songs are, if not quite ‘standards,’ almost standards. In other words, when I say ‘standards,’ I think they’ll live at least ten years. Now ‘The Sound of Silence’ has already lived about six years, and it’s still played, and it’s alive.”

“I don’t find it hard,” Paul said of living beyond the double-act. “That was over. I didn’t want to go on tour. I didn’t want to sing ‘Scarborough Fair’ again. I didn’t want to sing all of those S&G songs every night. When you’ve developed, it’s harder. Two people can go so far and then they’re locked to each other. There are just so many combinations of two. So that was over, as it should have been… I’m thirty now, so that’s a long time for that partnership… I’ve known Artie since I was twelve-years-old, and we were friends all that time… We grew up. From the musical point of view, in the time that he was off in the movies, Artie didn’t do anything musically. I was doing things musically, but to Artie it would have to go back to the old ‘practicing a song; have to learn the harmony.’ … I always felt restricted as a singer, partly because there always had to be harmony, and it had to be sung in the same phrasing, and then you had to double it. You couldn’t get free and loose with your singing, and—in this album—I am pretty free.”

When the twosome leaned towards disbanding, Clive Davis and Columbia were “tremendously discouraging. They didn’t want that split at all. They still don’t want it. The first form it took was self-delusion: ‘Paul has to get this out of his system.’ Then they would ask, ‘When do you think you’ll do the next S&G album?’ Which would bring me down. I’d be working on this album—it was important to me—and they would want to know when I was going to put aside this little ‘toy.’ [Clive] didn’t encourage me at all to do this. It became obvious that I was going to do it, and it was stupid [for him] to get in the way, [so he had] sort of a predictably conservative attitude… Everybody said, ‘What the hell’s wrong? Why don’t they stay together?’ And everybody said, ‘Gee, I always like S&G; boy, that’s too bad.’ It was too bad, but that was it. It was over. For the sake of me personally, it was great that I was doing this by myself—but, for the sake of the world, it wasn’t great. Nobody said, ‘Oh, boy, can’t wait to hear it.’”

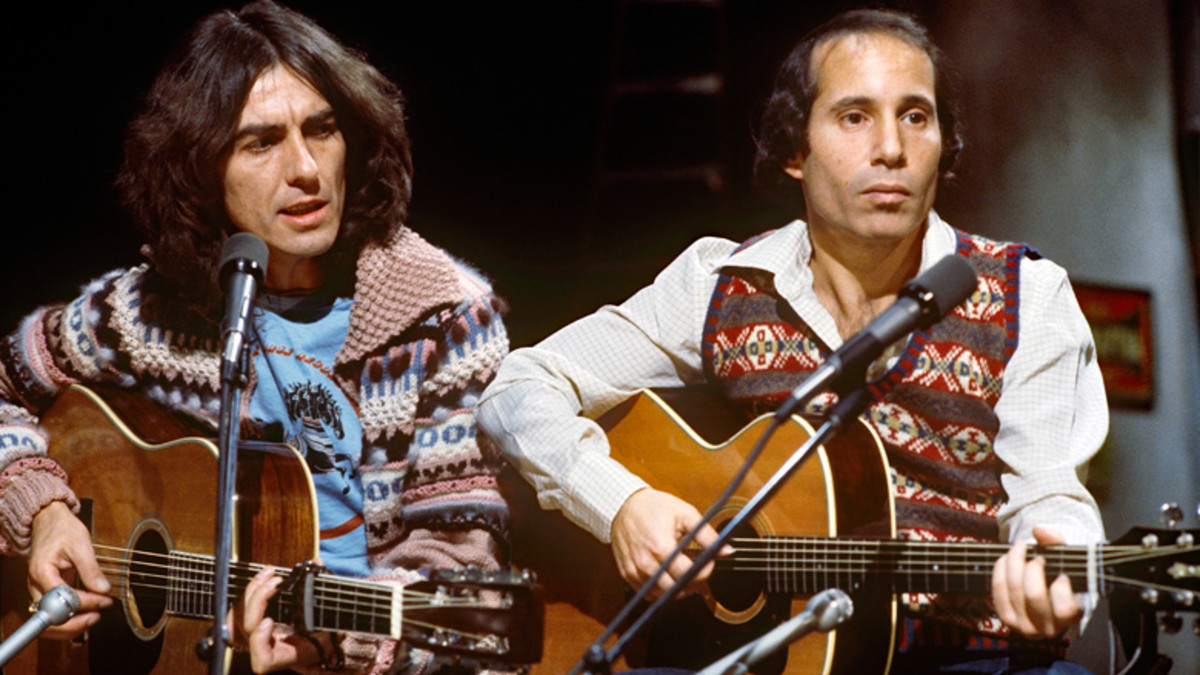

Actually, “George Harrison said to me, ‘I’m really curious to hear your album, because now you hear sort of what we are like individually, since the group broke-up, and I know what you were like together, and I’d like to hear what you’re like individually.’ And all the while in my head I thought, ‘This breakup is not really comparable to that Beatles breakup, because there was a tremendous interaction in that group that came from the sound,’ and I said to myself, ‘I write better songs now than I used to write years ago, so I’m going to make a better album, but nobody knows that. They won’t know it till it comes out.’ That was my fantasy. In fact, many critics said that. But the public didn’t in terms of buying the record, and that’s unsettling. I’m getting used to it now… At first I said, ‘Look, when it breaks-up, you’re going to have to start all over again. It may take you a couple of albums before people will even listen.’ But actually, emotionally, I was ready to be welcomed into the public’s arms…”

His album “Paul Simon” sold roughly 850,000 copies in its first few weeks of availability. “When people who are forty-years-old buy your albums, and they like your music… That’s what it’s about; that’s music. I don’t say, ‘Don’t you listen to this music—you—this isn’t for you.’ I want everybody to listen to it. I hope everybody likes it… I’m at the start and building slowly… Maybe I’ll never get there…”

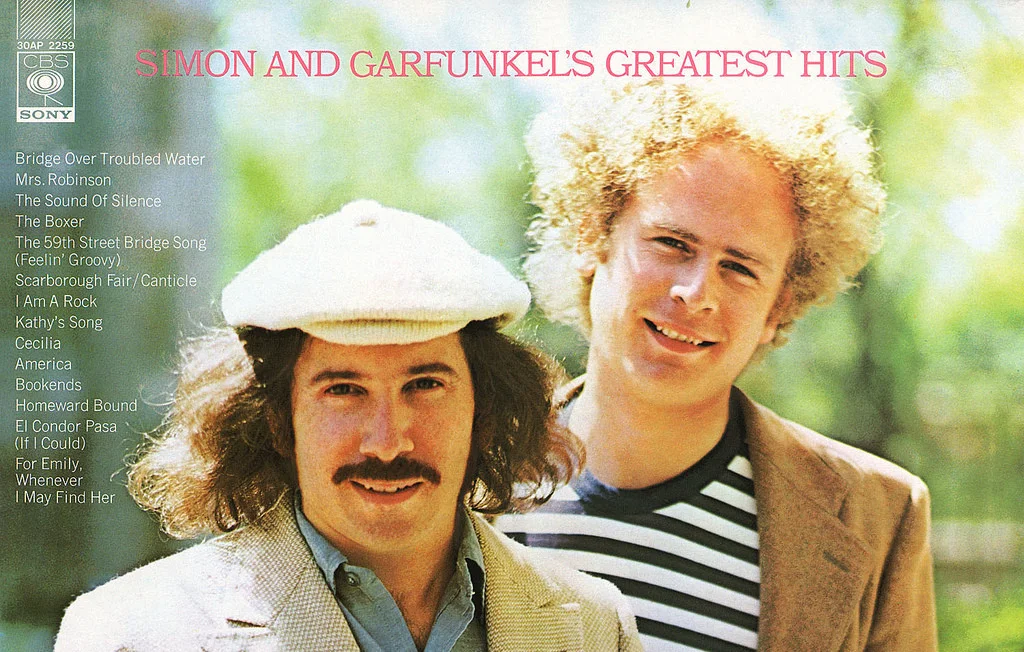

With their reunion looking improbable, Columbia released “Simon and Garfunkel's Greatest Hits” in 1972 to massive acclaim. It shot to the top of the album charts in the US and UK—remaining there for 131 and 179 weeks respectively—selling nearly fifteen-million copies and being certified 14x Platinum. “Greatest Hits” featured fourteen songs on two sides, comprised mostly of their big singles, recorded between March of ‘64 and November of ‘69.

“Clive once said to me, ‘S&G is a household word. No matter, however successful you’ll be, you’ll never be as successful as S&G.’ So I said, ‘Yeah, like Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. Don’t tell me that. Don’t tell me that statement, that ‘I’ll never be bigger than.’ How do you know what I’ll do?’ I don’t even know what I’m gonna do in the next decade of my life. It could be maybe my greatest time of work. Maybe I’m finished. Maybe I’m not gonna do my thing until I’m fifty. People will say then, ‘Funny thing was, in his youth, he sang with a group. He sang popular songs in the Sixties…’ That’s how I figure it.”

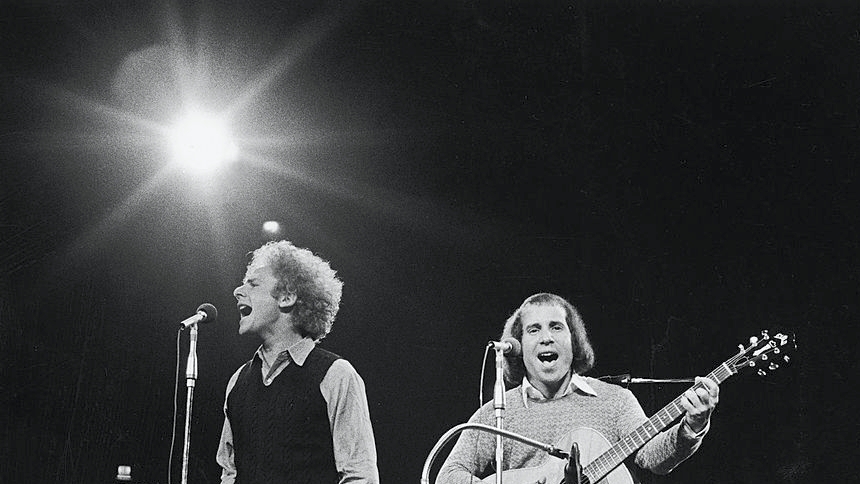

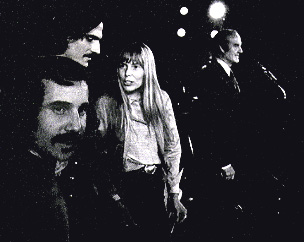

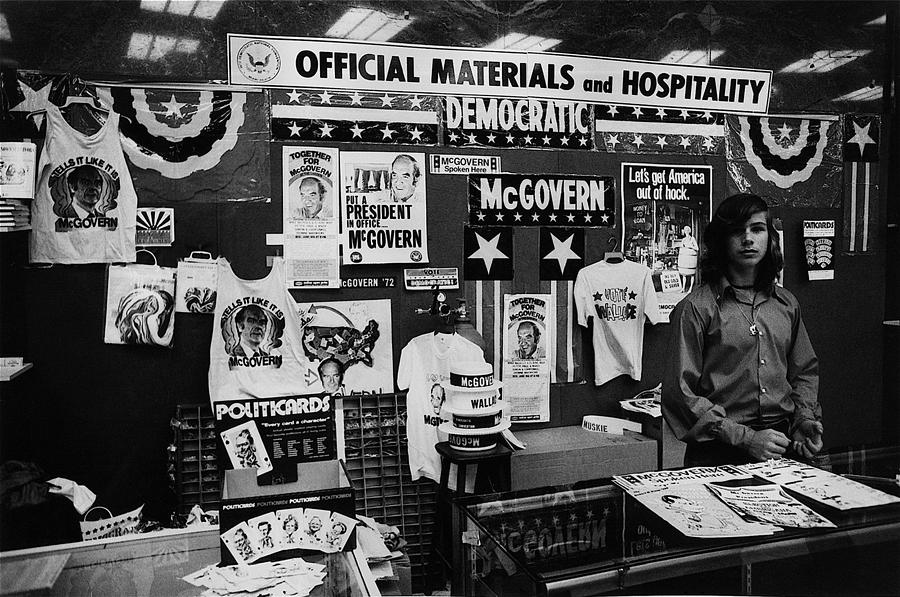

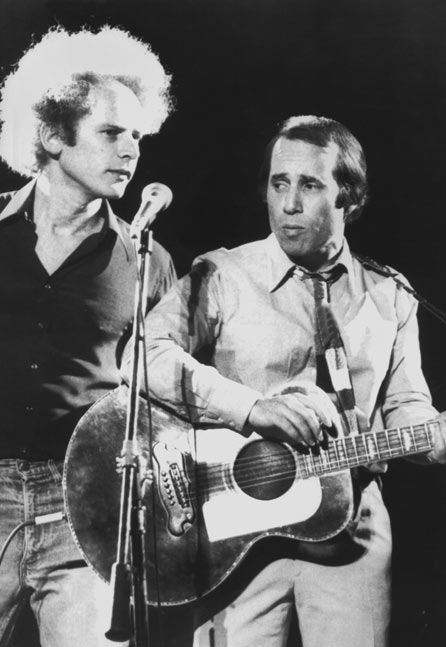

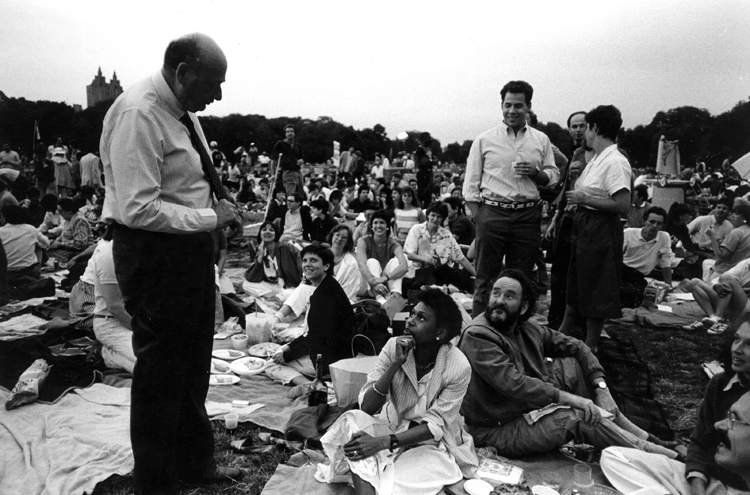

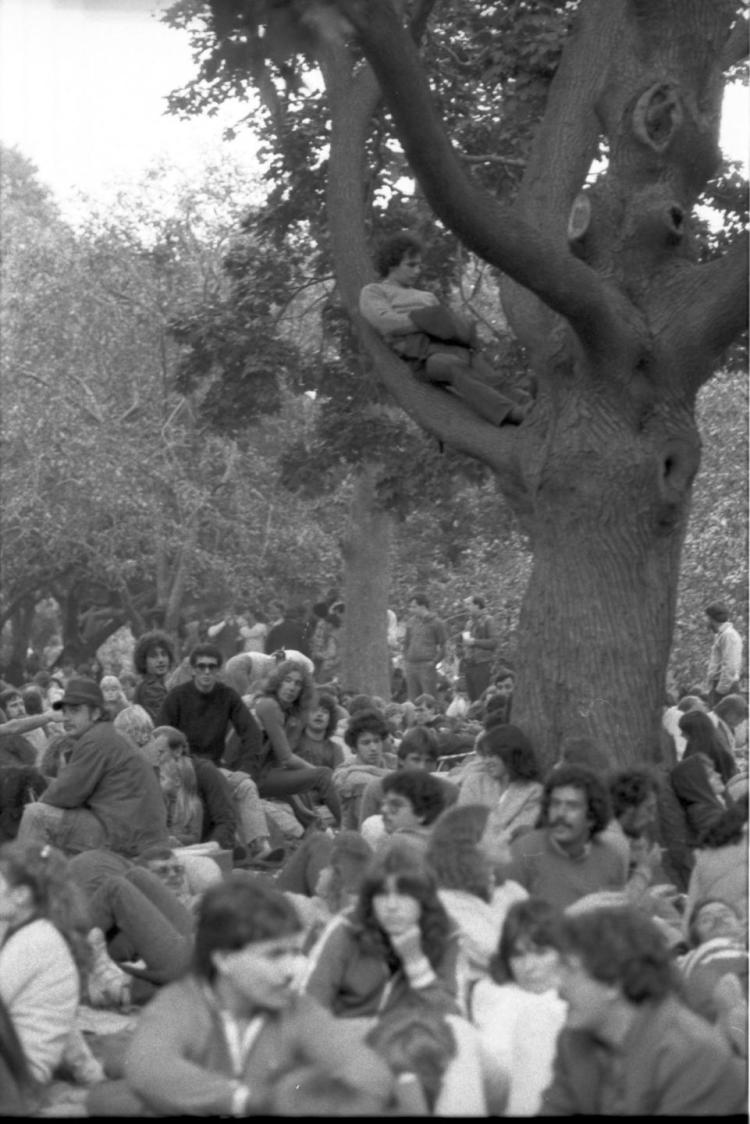

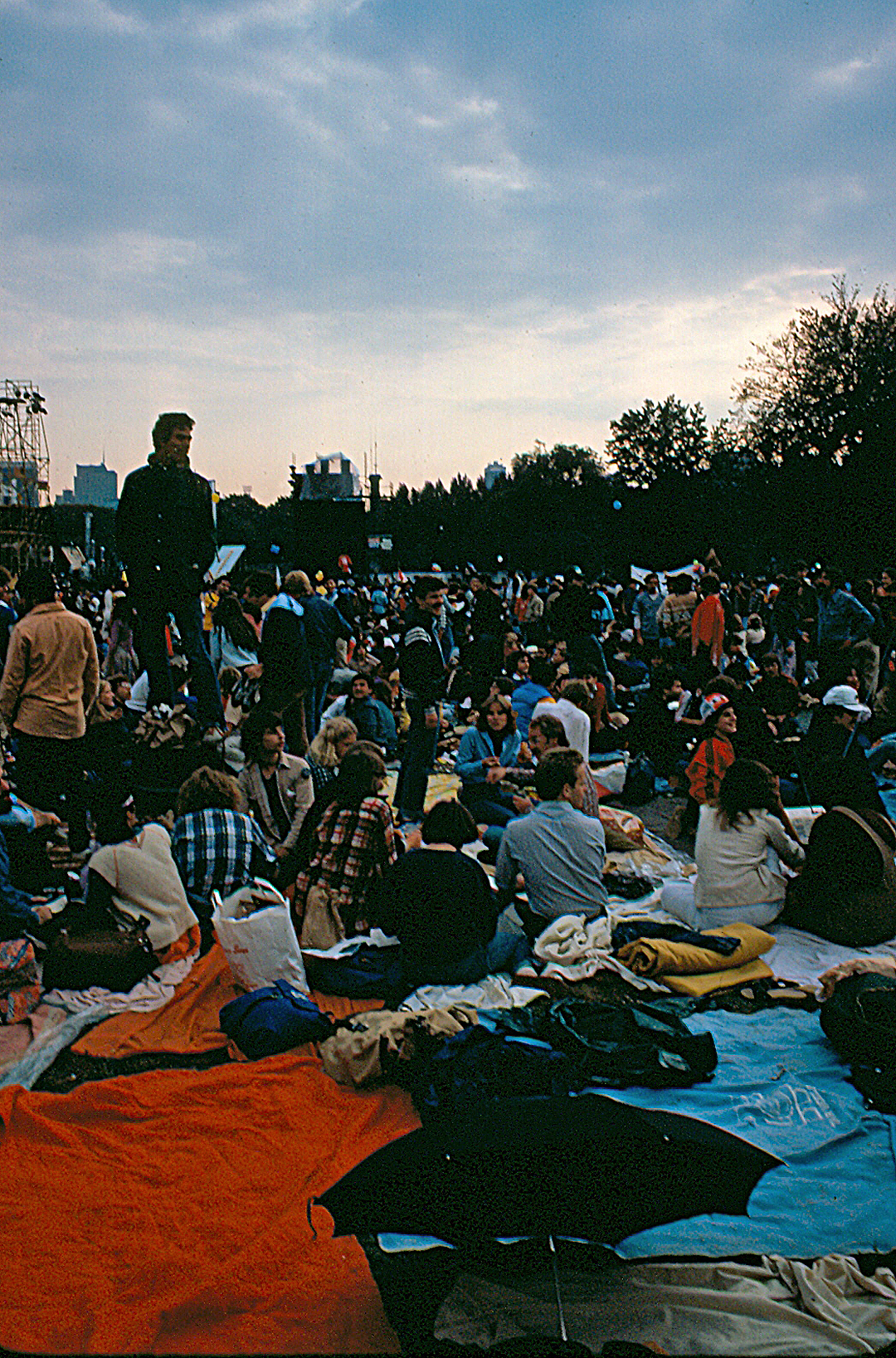

On June 14, 1972, the day of the release of “Greatest Hits,” Simon & Garfunkel reunited for a few hours at a concert benefiting the Democratic nomination campaign of George McGovern for president. In his New York Times article “Rock ‘n’ Rhetoric Rally in the Garden Aids McGovern,” McCandlish Phillips wrote of Madison Square Garden selling-out every seat to more than eighteen-thousand people, for a gross of half-a-million-dollars towards the McGovern campaign.

Warren Beatty, the actor/producer known for kickstarting New Hollywood with 1967's “Bonnie & Clyde,” conceived the idea of ‘Together With McGovern at the Garden’ as a means to interest the modern American in the Democratic candidate believed most capable of dethroning President Richard Nixon—the man who had presided over the worst of the Vietnam War and was now forming a symbiotic relationship with the Soviet Union's loftiest frenemy, China.

At Madison Square Garden, the pricier floor seats were “occupied by an older and more fashionably dressed crowd,” whereas “in the upper reaches, it looked like a rock concert, with most seats occupied by the dungarees‐and-polo‐shirts set.” Frankly, it was more a rock concert than it wasn't, with performances by Simon & Garfunkel, Dionne Warwick, Mike Nichols & Elaine May—a comedy duo revival—and Peter, Paul & Mary, who had also reunited for the occasion. Needless to say, it was an interesting night for everyone.

The theme of “bringing everyone together” that McGovern preached was typified by the one-night-only reuniting of the three main acts. In fact, this was what convinced Art to perform at the benefit. “That’s why I did it, I loved the show. It appealed to my showmanship. Much more than McGovern ever could to my politics. It’s selfish, I suppose. I loved the idea of those three acts, I thought it would be a terrific show.”

By the end, however, he wasn't so sure. “It was a strange, non-experience. It was the first time I had sung with Paul onstage in quite a while. We had ostensibly broken-up and here we were doing this thing together. And I did think beforehand that it would be a kick—some kind of novel experience—and yet after about three bars into the first song I had a very strong feeling, ‘Well, here we are again. This is where I left off.’”

It wasn't all cordial, and it wasn't all hostile; it was mostly tense, and awkward. Imagine: two old friends, closer than brothers, who more-or-less gave up on each other, and now fate has pulled them back to the same old harmonies. Everyone in the audience thinks, “Oh, it's so great to see them live,” and not one of 'em knows how deep the rift between them has become—in spite of their standing an elbow's width apart. So, these days, as Art understandably says, “We’re anxious to see each other whenever we see each other.”

Art swirled his gin & tonic, deep in thought. Jon Landau had asked him why Paul decided they should sing a verse of “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” and Art hadn't yet considered a rhyme or reason behind it. He looked to the ceiling and thought for a moment before musing, “Interesting question…” He looked down into his glass and his brow furrowed.

“He said that was an idea he wanted to do,” he snapped, as if the questioned had tripped a defense mechanism. “He thought that would be good. I don’t know what you want me to say. Cut me open and look at all my contradictory reactions to, uh, ‘Do I think that’s a good idea? Do I trust? Do I sense an ego trying to subtract from my ego?’ It’s the kind of thing I don’t want to get into, really. Things work in relationships and things don’t work. I don’t know how much I want to get into [your magazine] as far as examinations of things that don’t work, because they’re usually petty shit. Examinations of why things don’t work—negative things—can be lessons, or, enlightenment… Beyond the words of the songs, I felt that S&G projected the hopefulness of an ongoing friendship as a sort of a public message. I liked that about S&G. But then there are even deeper needs.”

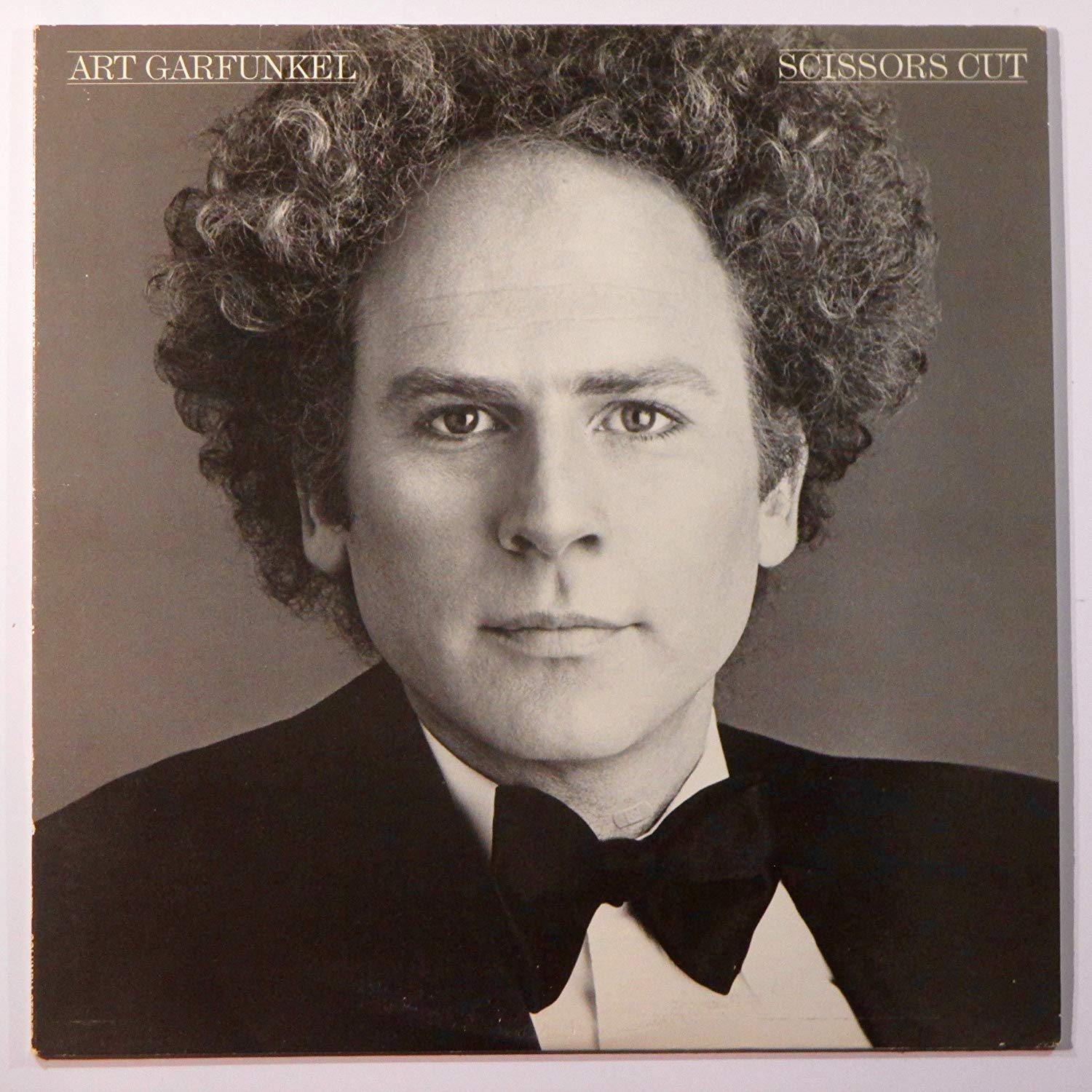

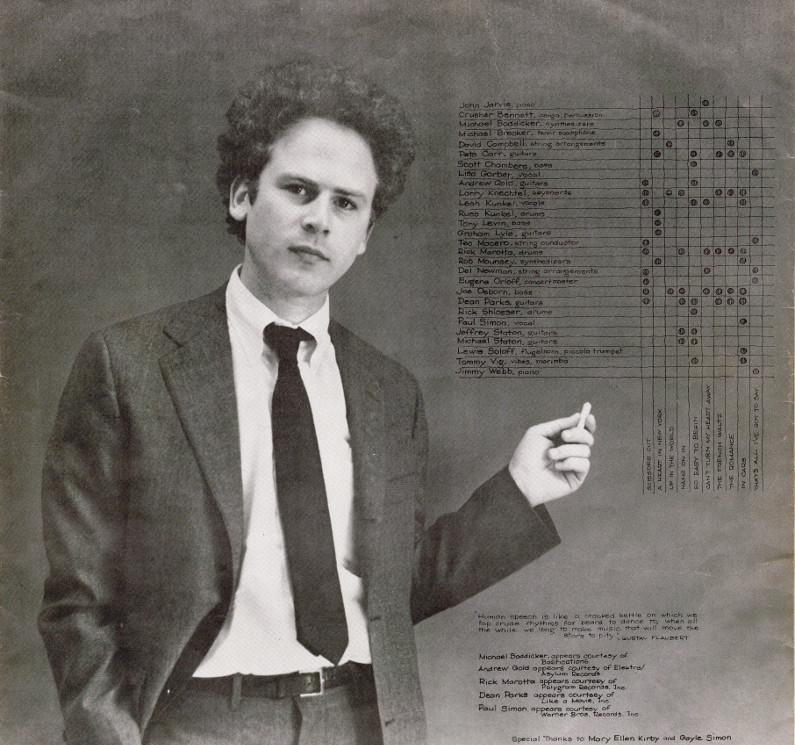

After soaking in the limelight at Madison Square Garden, and breathing the buzz of their “Greatest Hits” album, Art was convinced he needed to record a solo album. He looked back to his roots—his childhood influences—for inspiration, from the likes of Enrico Caruso, Nat King Cole, and Sam Cooke.

Elsewhere, while Paul was working on his own solo album, his depression was working on him. He met with a therapist a few days a week but wasn't making much progress. Like the earliest of his songs, he stayed swamped by thoughts and fears of loneliness and malaise; angst and anxiety.

“I don’t relax so much with Paul, nor he with me,” Art told The Telegraph, adding that the cracks of their broken friendship ran “deeper than you may know.” “He’s too damn special; too talented; too turned-on, and so am I. You’ve got to bring your ‘A-material’ to a phone call. It works brilliantly for presenting this charged energy but it is too heightened. He is the funniest guy I know and he knows me better than anybody knows me—that’s great power.”

“He is a magnificent guitar player—what a musician. We’ve had shows in the past where the disaffection, the argument, the lack of sync was going on right before the curtain opened and ‘Now it’s showtime!’ You go up to the two mics, you feel a cold shoulder to your left, you open your mouth and hear this beautiful musical blend. A little bubble surrounds Paul and Artie and the guitar-playing, and you listen as fine as you can listen, and chase after the beauty of each next line. I can’t quite have this much fun with anybody… He’s so musical. He’s so nuanced. He’s the closest thing on earth to what I do. Well—that’s a thrill.”

“If I were to be bothered by it, I would be a spoiled diva. To form a friendship with such a musical cat in my young years is to have my life enriched permanently.” A solo career was an exciting prospect, but Art couldn't unwrap his head from the glorious years of S&G. It seemed he wanted it when he didn't have it, and he didn't want it when he did. Nearly his whole life had been spent beside Paul, “in the control room,” and he carried a torch for it. “I spent all that glory time just loving the dials; the speakers; the musical possibilities. To know that the whole world is watching is unparalleled as a rich life experience. Nothing is quite like that.”

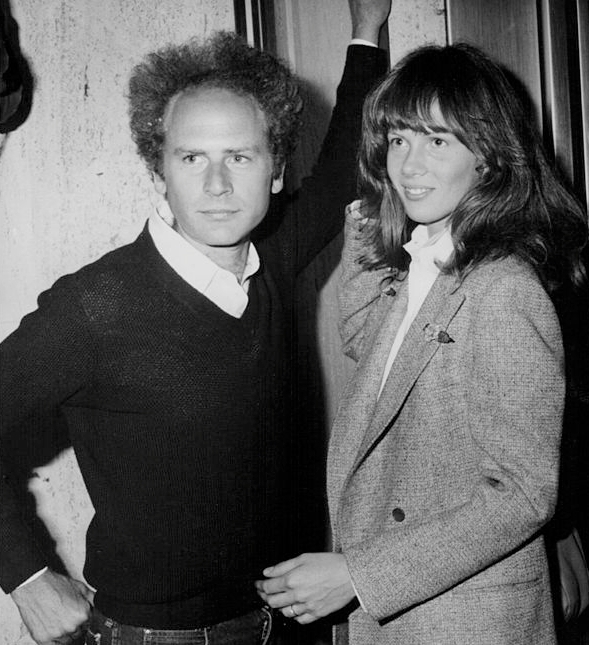

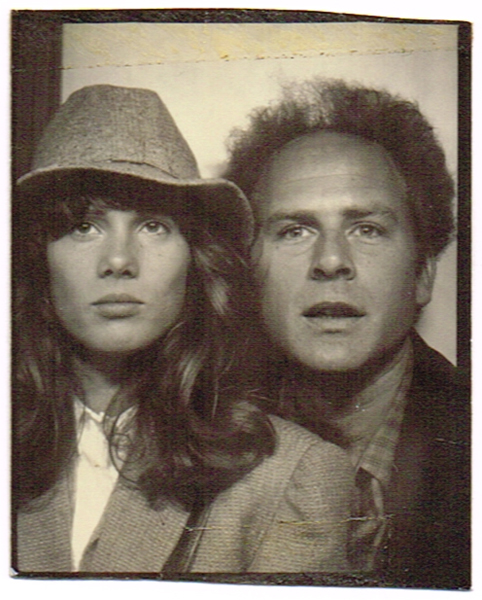

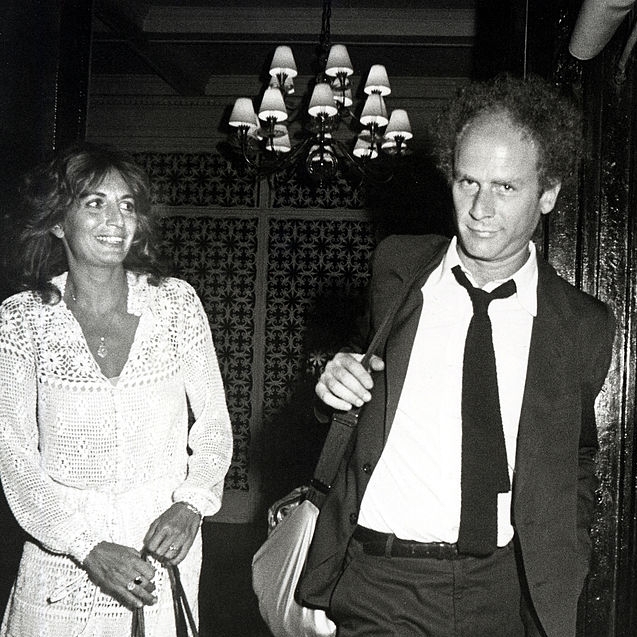

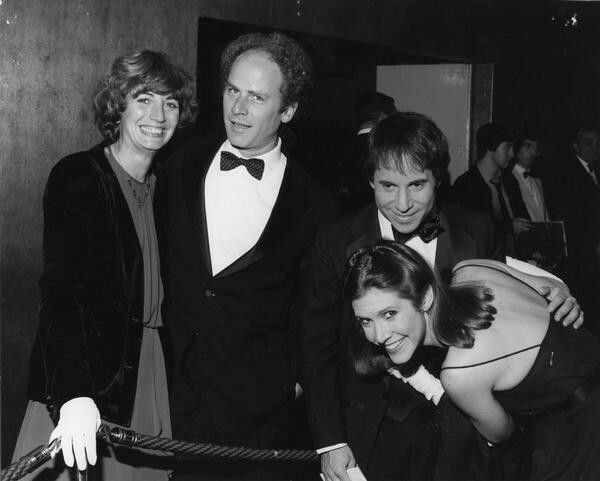

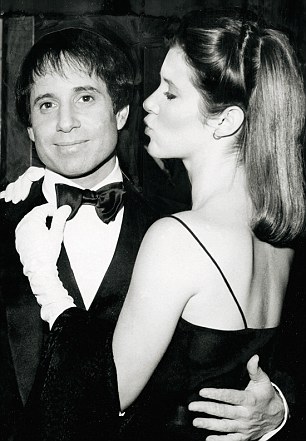

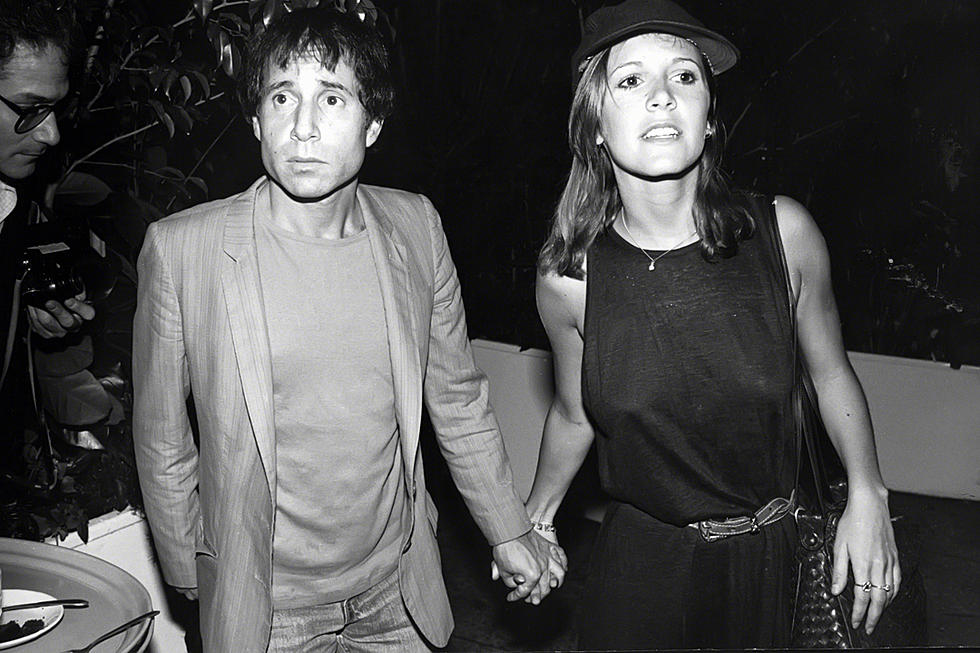

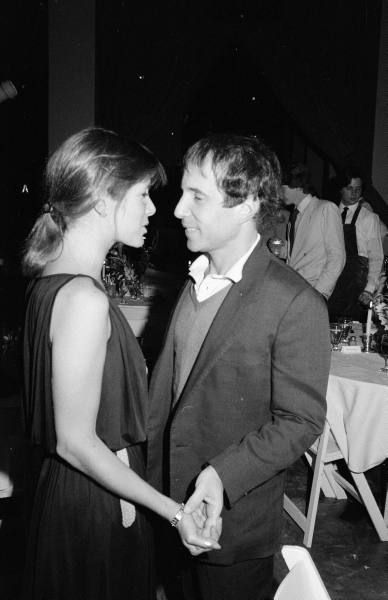

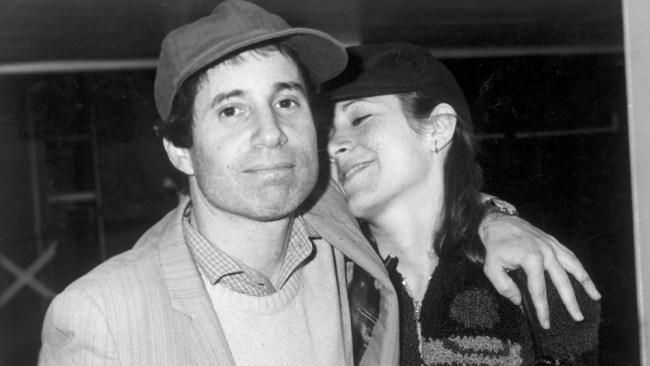

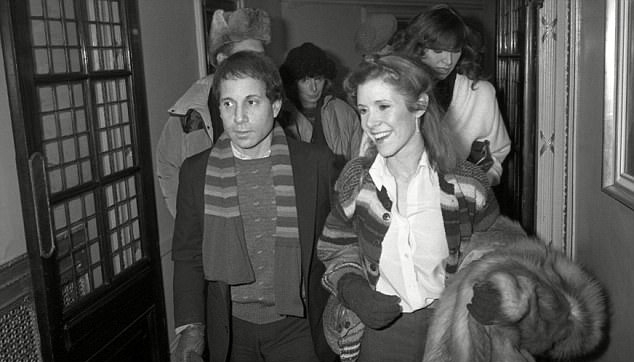

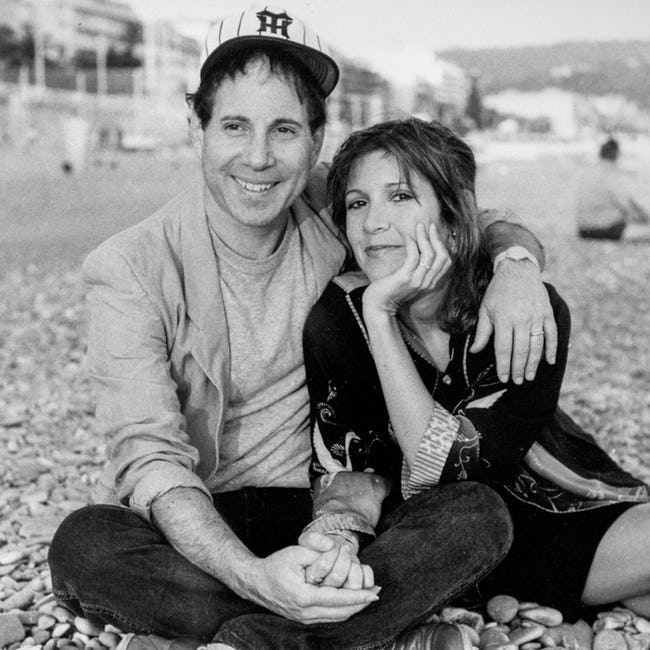

Art Garfunkel and Linda Grossman were wed on the first of October, 1972, at her home in Nashville. It was a small ceremony. Paul was there.

“She’s four years younger than I am,” Art told Rolling Stone a year later. “She came out of architecture school to work as a graphic designer up North some five years ago… She said she had seen me once in concert at her school—Washington University—years before that. She was interested in me.”

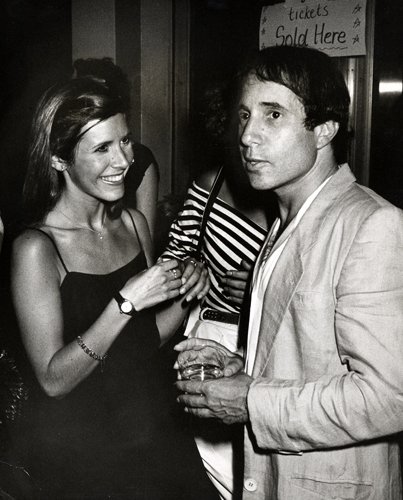

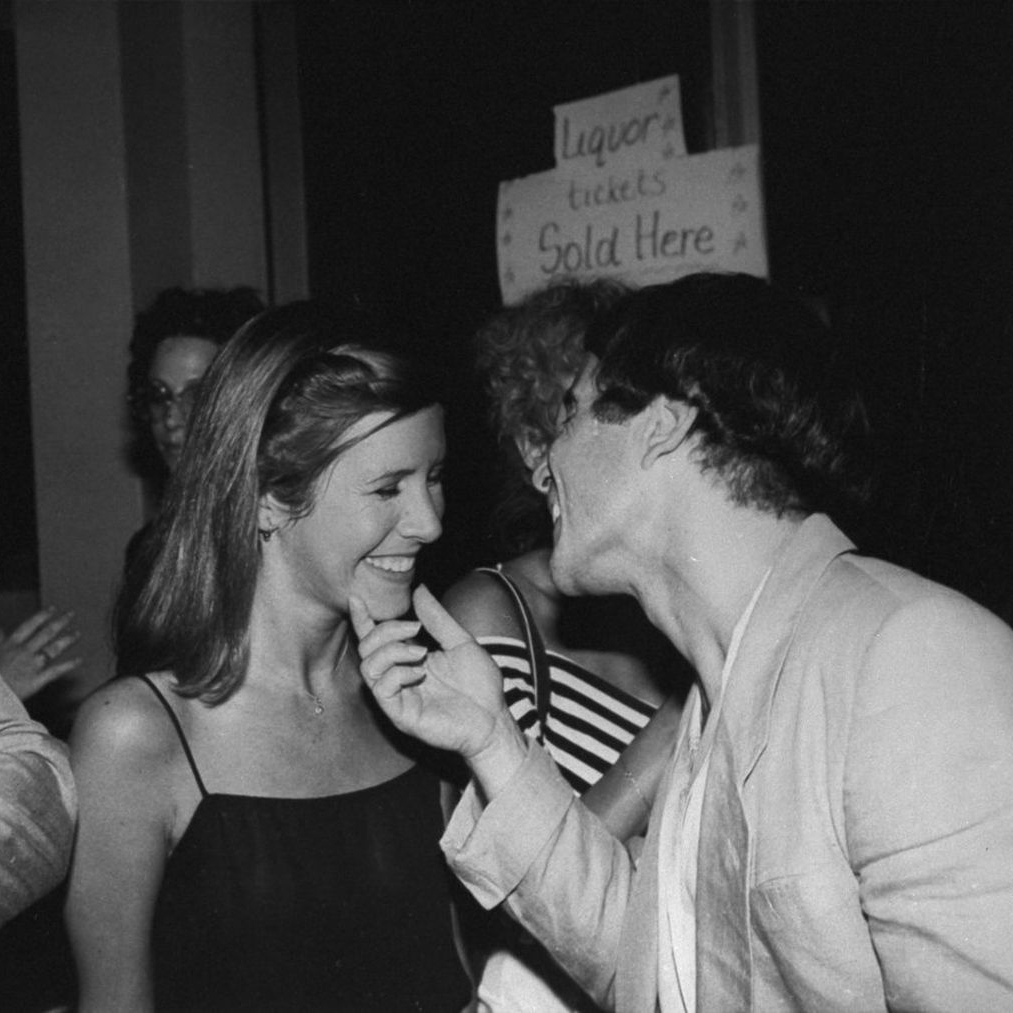

“[We met] on the streets of New York. In the beginning of the spring of ’69, I had a two-week break from ‘Catch-22,’ and I was on 55th and Park Avenue, going to a restaurant with Mort Lewis for lunch. We were laughing about something, and Linda—who was visiting New York from Boston—passed me in a cab…and jumped out a block later… Now, I spotted her halfway up the block coming toward me and I thought, ‘There’s a girl I could get serious about.’ At that point in my life I was looking to stop running around and playing around—and to my tremendous pleasure, she was heading straight toward me. She walked up and said, ‘You’re Artie, aren’t you?’ I, of course, was ready; my rhythm was already going. I think I asked her to marry me about the second sentence.”

“[I had] never had that kind of feeling. She said she was very put-off by my being so direct… She said No, and she pulled back a little bit and I said, ‘Well, there’s a church nearby. I think we could work it out.’ I invited her to the studio that night. We were working on ‘The Boxer.’ She was reluctant, but she thought she’d try it. She came, sat over the engineering console—with her chin on her wrist—staring at me, Paul, and Roy for four hours. She was going to know everything. I was impressed and flattered. I like people who third-degree me; who stare at me. I feel they’re interested. And we went out afterwards, and I was very charmed, and we dated a lot. … It took us about three years though before I had the courage to ask her to marry me.”

They were to divorce in 1975. He has since said the marriage was ‘turbulent’ and ‘bitter.’ He later confessed, with apathy, that he did not like her or care for her much during their three years of holy union—and, after the divorce, he never spoke to her again. She was like Litchfield Academy: something he thought he wanted yet never considered in detail, until he was already in over his head. And, like Litchfield Academy, he got out.

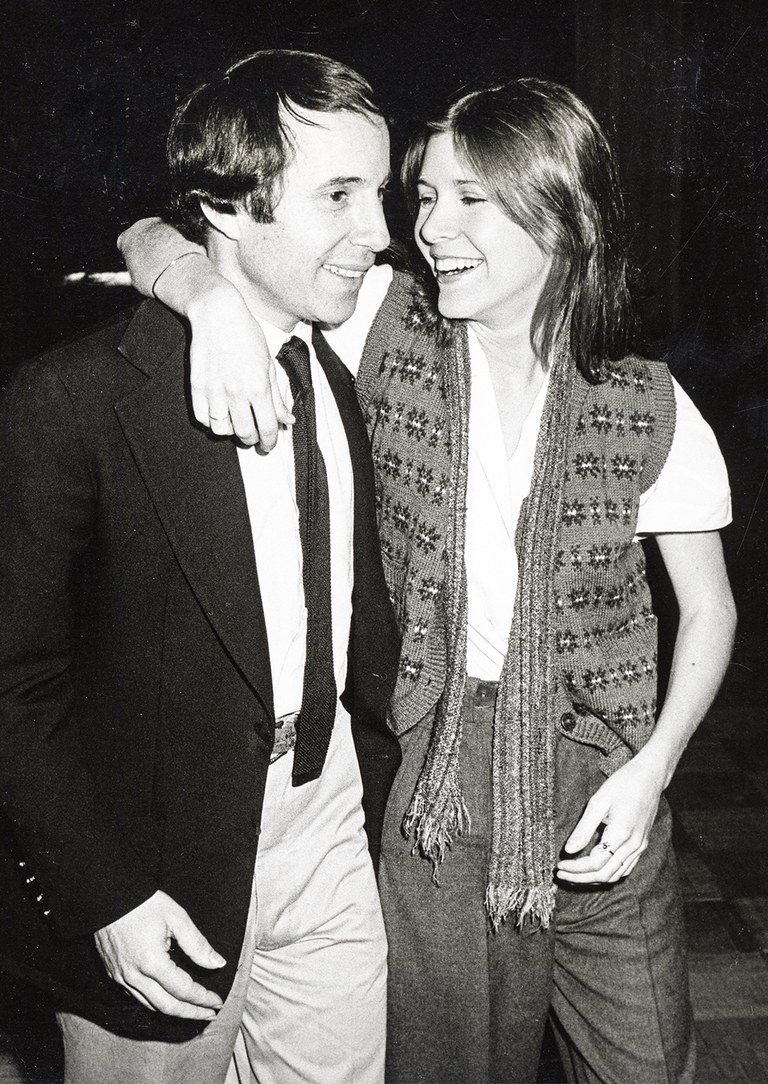

Decades later, when asked what the best part of fame was, Art replied after a moment of reflection, “The girls were a big thing, because suddenly you’re not such a loner and not so different from everyone else… I really had no idea what most of the women thought; that’s a consensus kind of question. I always assumed that there was a great deal to be interested in Paul Simon. Certainly [for] anybody who was on to the idea that all these words we’re singing are his words.”

But Art was “the tall handsome figure” and “the better singer,” which came with its own allure. “I don’t know how much an appearance of detachment—which I think I had more than Paul—makes you curious… I don’t know what they thought… But I did sit up a lot of nights talking with kids about their families, aspirations…”

“Simon & Garfunkel had a peculiar type of groupie,” Paul told Rolling Stone in 1973. “We had the poetic groupies. The girls that followed us around weren’t necessarily looking to sleep with us as much as they were looking to read their poetry, or discuss literature, or play their own songs… Maybe that was the best thing for me, because to a great degree it embarrassed me to pick-up somebody on the road, because it was so obvious that you weren’t interested in them. I felt it was insulting. You obviously didn’t care anything about the person if you were just picking them up to take them back to a Holiday Inn with you, and it required pretense. You had to pretend that there was something more to it. Or else you had to pretend that you didn’t care at all what they thought, or you didn’t care at all about other people. And I couldn’t make either pretense. I wasn’t terribly involved with them as people, but—on the other hand—I couldn’t do something that I thought was insulting.”

“Ultimately, I wound up going back to the room and smoking a joint and going to sleep by myself. Most of the time, sometimes not… But toward the end I always avoided any contact with people after the show. I never encouraged it. There were always exceptions, but, in general—compared to what I’ve read about most rock groups or pop groups—for me—and I can’t speak for Artie—I wasn’t into picking-up girls on the road. Couldn’t do it. Too embarrassing to me. I wasn’t interested in their poetry either.”

At the end of the year, and into 1973, Paul collaborated with Roy Halee and a fleet of diverse instrumentalists to create the pop/folk “There Goes Rhymin’ Simon,” released by Columbia in May. It reached #1 on the Cashbox album charts and #2 on the Billboard 200, stayed only by his friend George Harrison's “Living in the Material World.” It would be nominated for ‘Best Male Pop Vocal Performance’ and ‘Album of the Year’ at the 1974 Grammy Awards, though it would lose the latter category to Stevie Wonder's “Innervisions.”

“There Goes Rhymin’ Simon” produced six singles including “Loves Me Like a Rock” which peaked at #2, unable to unseat Cher's “Half-Breed.” In “Loves Me Like a Rock,” Paul characterized the confidence that derives from love, saying, “When I was grown to be a man / And the Devil would call my name / I'd say ‘now who do / Who do you think you're fooling?’ / I'm a consummated man. / I can snatch a little purity.”

The Denver Post praised “There Goes Rhymin’ Simon” as “a brilliantly executed masterpiece, and surely the finest album in three years,” specifically referring to “Bridge Over Troubled Water” and Neil Young’s “After the Gold Rush” of 1970. The ten songs on Paul’s second post-S&G solo album showcased his breadth of flavor, leading Robert Hilburn to say, “from a touch of gospel to an infectious trace of Jamaican rhythm to a hint of the old Simon & Garfunkel grandeur, Simon's new album firmly establishes him as one of our most valuable and accessible artists.”

The variety of genres he displayed included the choral, rhythmic Dixieland style, as showcased in the fourth single “Take Me to the Mardi Gras.” “Hurry take me to the Mardi Gras / In the city of my dreams. / You can legalize your lows / You can wear your summer clothes / In the New Orleans.” The third single, “American Tune,” swung into weary melancholia à la the old S&G sound, now latticed to the tune of Johann Sebastian Bach's “St. Matthew Passion.”

In an interview with Tom Moon, Paul said, “I don’t write overtly-political songs, although ‘American Tune’ comes pretty close, as it was written just after Nixon was elected.” The incumbent’s sweep of America depressed Paul in a manner similar to the “worst of two evils” outcome of the 2016 Presidential Election: the country had not been in a good place, and it seemed now to be locked-in for another four years of downward spiral.

“And I don't know a soul who's not been battered / I don't have a friend who feels at ease / I don't know a dream that's not been shattered / or driven to its knees / But it's all right, it's all right / We've lived so well so long. / Still, when I think of the road / we're traveling on / I wonder what went wrong.” Here, Paul details the progressive American’s perspective on the duality of optimism and despair, and how the only way to survive such turbulence is to resign to the struggle and keep moving forward, despite the hardship, confusion, and fatigue that await.

“And I dreamed I was flying / And high up above my eyes could clearly see / The Statue of Liberty / Sailing away to sea / And I dreamed I was flying.” “We come on the ship they call the Mayflower. / We come on the ship that sailed the moon. / We come in the age's most uncertain hour / and sing an American tune.”

Reviewers found the confidence of “There Goes Rhymin’ Simon” refreshing, describing the album's underwritten personal and sociopolitical messages as strong and relatable. The best example of this acclaim belongs to “Something So Right,” the sorrowful repent to his then-wife Peggy. In this song—which he had written as their marriage crumbled—he illustrated his failures as a husband in comparison to all of the selfless good she had provided him.

“They've got a wall in China. / It's a thousand miles long. / To keep out the foreigners / They made it strong. // I've got a wall around me / You can't even see. / It took a little time / To get to me.” As Robert Hilburn later wrote, “In the months after the release of ‘Rhymin' Simon,’ you couldn't tell the state of [his] private life by his public success. While his music was all over the radio, he was still grappling with many of the old issues of fame, loneliness, writer's block, and now—above all—his marriage.”

“Peggy didn't know what to make of Paul's increasing time away from the apartment. Without any evidence that he was unfaithful, she still found herself wondering when Simon would come home late and take long showers if he was trying to wash away ‘the shame.’ Asked years later about those nights, Simon said No, he spent all that time in the shower trying to wash away ‘the sadness.’” “When something goes wrong / I'm the first to admit it / I'm the first to admit it / But the last one to know / When something goes right. // Well it's likely to lose me / It's apt to confuse me / It's such an unusual sight. / I can't get used to something so right / Something so right.”

Paul blamed himself for all that went wrong with their marriage. Peggy had devoted herself to their newborn son, Harper, whereas he was distancing himself per the demands of his career and the woes of his depression. “Ultimately, I wasn't ready for marriage,” he told Robert Hilburn. “The marriage didn't solve the loneliness. I knew right away I had made a mistake. I didn't know how to be a good companion. I wasn't a very mature person. I didn't understand that you had to work at problems. I wanted the marriage to solve my problems.”

“Something So Right” was nominated something-so-rightfully for ‘Best Song of the Year,’ striking a chord with Paul. Nearly a week after the announcement, he informed Peggy that they needed a divorce—for the sake of them both. She was blindsided. “It's not that I thought we had this fairy-tale relationship. In some ways, we were living in different worlds. Even so, I had no idea he wanted out of the marriage. There was no scene or shouting match—simply acceptance. I couldn't believe that he wanted to marry me in the first place. I liked him a lot—I was even obsessed about him in some ways—but I didn't think I was worthy. He was already rich and famous and I didn't have much going for me except for my looks. I kept asking myself, ‘Why does he want to marry me?’ ‘Aren't I the lucky girl?’”

Looking back, Paul understands now why everyone was so shocked by his unhappiness. “Most people look at me and wonder, ‘How could that guy be depressed?’ And I now feel that people were seeing a more accurate picture of me than I was. I eventually realised, ‘Jesus, all I've been looking at is this thin slice of pie that has got the bad news in it, and I'm disregarding the rest of the picture.’ You could say that being short is bad news; not having a voice that you want; not looking the way you want to look; having a bad relationship. Some of that is real, and if you start to roll it together, that's what you focus on. I was unable to absorb the bounty that was in my life,” but, in 1973, he had already thrown it all away.

He took nothing home from the Grammy Awards of 1974, and yet, he was proud. “There Goes Rhymin’ Simon” didn’t change the world but, as his old manager Mort Lewis said, “I think it showed Paul that he could stand on his own.” His last three records had been nominated for the industry’s greatest annual honor. Clearly, he did not need to lean on Art Garfunkel—or anyone, for that matter—to succeed.

Things were looking up, as Paul fantasized in the lead single “Kodachrome,” which peaked at #2 on Billboard’s Hot 100, kept short by his friend George Harrison’s “Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth).” “Kodachrome” was sentimental, evocative, and “cheerfully antisocial,” kicked-off by sass: “When I think back / On all the crap I learned in high school / It's a wonder / I can think at all.” Named for the Kodak 35mm film that middle-class Americans often recorded their home videos on, between the 1940s and 1960s, “Kodachrome” was an anthem of nostalgia for the Baby Boomer generation.

“Kodachrome / They give us those nice bright colors / They give us the greens of summers / Makes you think all the world's a sunny day.” As a trailing member of the attributed generation, Mark Martin spent his childhood in the sunset of America’s prosperous years. He wrote of a visceral memory triggered by Paul’s lyrics, recounting, “I am twelve and in the backseat of my mom’s 1965 Pontiac Safari station wagon. It’s hot. It’s summer. No A/C so the windows are all down. We are crossing the Savannah River into Georgia and downtown Savannah. I can still smell the paper mills and swampy acrid smell. We are on a long drive back to Miami. No interstates… I can still smell that paper mill and see that bridge in my mind when I hear this song, [thinking] ‘Everything’s going to be okay.’”

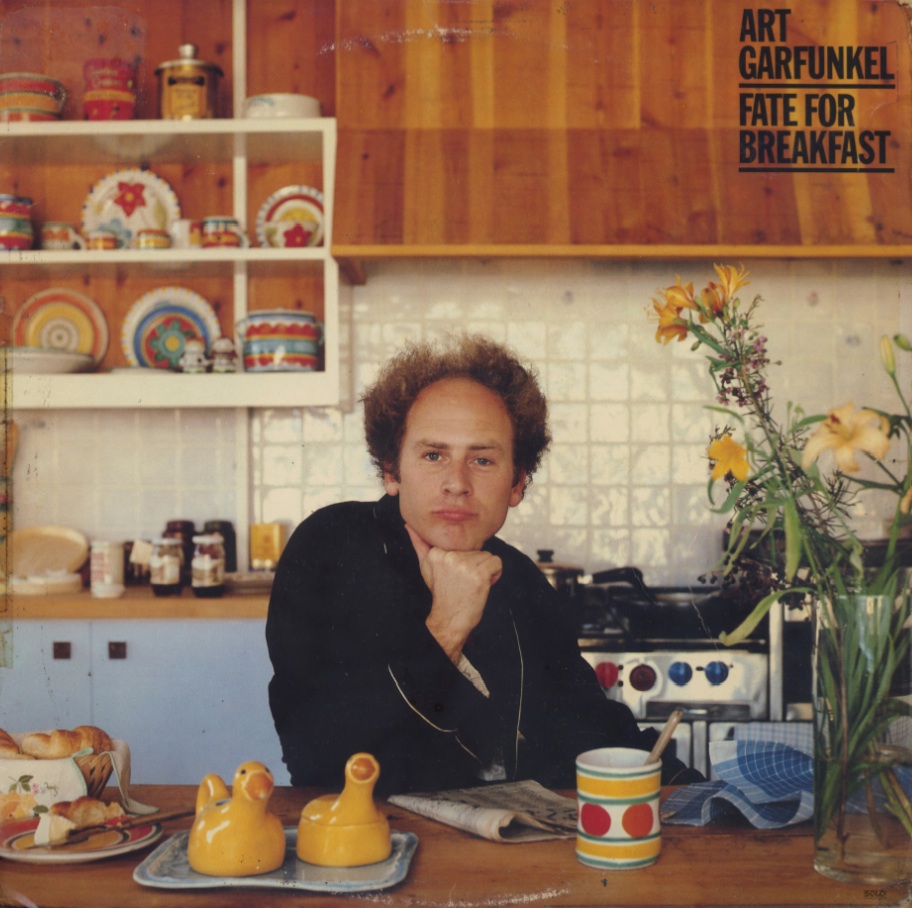

Roy Halee was tied-up for six months with Paul, recording “There Goes Rhymin’ Simon,” so Artie—who was only willing to work with Roy on his first solo album—felt obligated to postpone his recording until mid-1973. Art was twisting in the wind without his former creative partners, and Roy Halee was the last remaining piece of the braintrust behind the five albums of S&G.

In the past, Roy had always seemed to agree with Art over Paul on the direction for certain arrangements. The ‘sound’ Roy Halee sought to imbue S&G with had ran parallel to the ‘sound’ Artie desired—that of a more traditional folk than a rockish folk.

Art required “the most stability possible” by having Roy Halee and other familiar faces from S&G sessions around him. “That was my first instinct: to see if I could pick-up where I left off. But that was very painful the first month or two… ‘Cause, you know, everything is wide open… infinite possibilities, in terms of what record you want to make. I had no budget restrictions; no time restrictions; I could do whatever I pleased. And when you’re swimming around in this tremendous sense of possibility, you’re apt to be most fearful.”

“I started the album in spring of ’72 and I started thinking about it…a year earlier. ‘Forced to do it’ is close, by—I don’t know—the circumstances. I like to make music; I have some experience doing it; I have a large audience available to me—I felt it behooved me to relate to all of this. I had to put it all together and try an album.” Art wasn't picky in planning the tracklist, choosing “Any songs that I could get off on.”

“I was full of fear at the beginning of this project… in a kind of a semi-retirement.” Fortunately the delay gave Art more time to prepare—but, of course, he had a team for that. Columbia paid for ten songs written by Paul Williams, Roger Nichols, Van Morrison, Randy Newman, Jimmy Webb, and others, including a Johann Sebastian Bach piece reworked by his wife, architect Linda Grossman.

Throughout the summer of ‘73, Art and his team recorded at a pop-up studio inside Grace Cathedral in San Francisco. Production and instrumentals were provided by a team of thirty-four people, including Roy Halee, Jerry Garcia, J.J. Cale, Joe Osborn, Louie Shelton, pre-schizophrenia Jim Gordon, Mark Friedman on recorder, Jimmie Haskell, Larry Knechtel, St. Mary's Choir, Tommy Tedesco, and—briefly—Paul Simon.

“Angel Clare” was released on September 11, 1973, and while it didn't get the greatest reviews, it wasn't the worst thing to have ever happened on a September 11th. Critics had mixed opinions. “Angel Clare” climbed slowly to #5 on the Billboard 200, onward to sell half-a-million copies and be certified gold by the RIAA. In the UK, it climbed to #14 on the albums chart and was certified silver, indicating at least 60,000 units sold.

Art borrowed the album's title from a character in the 1891 Victorian novel “Tess of the d'Urbervilles,” by Thomas Hardy, which was a sexual scandal in its day. “It’s a name I like. Comes from literature. The English majors will know. In a sense I wanted to play right into—rather than back off of—this description of me as sweet.”

Art did one concert to promote the album but otherwise, despite the pleas of Columbia's A&R executives, he did not tour. As for his reasoning, “Well, you do what you feel like doing. Sometimes I feel like being onstage and singing, when the mics are good and the sound is right. But I think I’d rather make another album.”

Art made the cover of Rolling Stone in October, and Newsweek featured him in an article titled “Solo Art.” On his own website, years later, Art wrote, “When he and Paul Simon ended an eleven gold record partnership in 1970, Art Garfunkel was on the road to Hollywood stardom (Catch 22 and Carnal Knowledge). Now he realizes, ‘Acting was just a diversion. I've always felt committed to music; I love to sing.’”

“Sing he does in his new solo album, ANGLE CLARE [sic]; his first since the sound of silence descended on Simon & Garfunkel. Garfunkel has painstakingly collected a roomful of songwriters, including Jimmy Webb, Van Morrison and Randy Newman. Most of the songs are upbeat and…unremittingly cheerful…the appeal of that high, sweet tenor voice is forceful. Even Simon's mother admitted that Garfunkel was the better singer.” Yeah, sure.

The first single, “All I Know” by Jimmy Webb, peaked in the US at #9. It was the highest any Art Garfunkel single would ever chart.

After biffing the first two takes on “Traveling Boy,” the third single and the album's opener, Art finally hit the volume required for the song's crescendo. “Traveling Boy” tells of a drifter who leaves a one-night-stand before daybreak, and he feels kinda bad about it but not “too bad.” Larry Knechtel provided the opening piano work—an improvised ditty that was retooled until it pleased Art's ear.

The second track, “Down in the Willow Garden,” waxes poetic from the perspective of a psychopath killing a girl and hiding her corpse. Art's gentle voice stands juxtaposed against the lyrics, the same way “Pumped-Up Kicks, “Semi-Charmed Life,” and “MMMBop” sound lighthearted and fun until you listen closer and realise how fucked-up their stories are.

“Down in the willow garden / Where me and my love did meet, / As we set there a courtin', / My love fell off to sleep. // I had a bottle of burgundy wine, / My love she did not know. / So I poisoned that dear little girl / On the banks below. // I drew a saber through her, / It was a bloody knife, / I threw her in the river, / Which was a dreadful sight.”

“Down in the Willow Garden” was one of Art's favorite old country songs. When he and Paul were boys, they'd play the Everly Brothers record that featured it, and they'd cross-harmonize with the vinyl. For the last verse of the song, Paul flew out to the San Franciscan church and polished off their old harmonies. Art was delighted. However brief a reunion it was, it felt like returning home after a long journey.

Four months later, he changed his mind. “I don’t really miss Paul Simon in any way,” he told Rolling Stone. “I can appreciate his writing and feel how much I would dig to sing some of the songs, but [it's] pretty much the way I would feel about any writer. Paul sure is strong lyrically—not too many around as strong.”

Jerry Garcia of The Grateful Dead played lead guitar on “Down in the Willow Garden,” though it was later washed-out by Roy Halee in the mixing. Garcia had wanted to shred some dainty frets but Art didn't want any improvisation; he wanted it played straight, like it had been on the Everly Brothers record. Upon hearing the final cut, Garcia was considerably disappointed; his guitar had been lost in the noise of the arrangement, which he called “an overdub in a sea of overdubs.”

I'm not sure how much Van Morrison was paid for his contribution, but the third track, “I Shall Sing,” is primarily built around a chorus of “La la la la la la la la, / La la la la la la la. / La la la la la la la la, / La la la la la la la la la la la.” So that's, you know, what it is.

The fourth track of “Angel Clare” was “Old Man,” penned by Randy Newman, who you would recognize immediately if you heard him sing. Art must have followed Randy's sheet music to a T given how it sounds as unsettling as any other Randy Newman song.

“Won't be no God to comfort you, / You taught me not to believe that lie. / You don't need anybody, / Nobody needs you, / Don't cry, old man, don't cry. / Everybody dies.”

Critics were unimpressed and rather off-put by “Old Man,” due to Randy's lyrics and Art’s melody-leading interpretation. Randy Newman, however, said he loved it. Stephen Holden of Rolling Stone considered “Old Man” to be an afterthought, calling it indicative of “the chief trouble with the album.”

“Backed by saccharine violins, Garfunkel tries to turn this ironic little masterpiece of absurdity and fatalism into a sentimental eulogy. Here, [Art & Roy] demonstrate most acutely their tendency to ride herd over any and all material in the interests of aural beauty. Where a song is congenial to this end, the result is an opulent—if somewhat overcalculated—success. Where it is not, the result is prettiness for its own sake—which is pretty enough for me, if I don't listen too closely.”

Holden respected the eighteen months Art devoted to “Angel Clare,” and he was glad to see the other half of S&G return to the studio, but Art's goal of “monumental Romanticism” was achieved only at the steep cost of “aesthetic sacrifices.” In a later review, as the Rolling Stone notes, “The lyrics are clearly secondary…”

“The virtues are its choirboy loveliness,” whereas “the limitations are interpretative; Garfunkel employs too uniform an approach to too wide a range of material. He wants to make everything pretty, and he invariably succeeds, though in so doing he sometimes obscures the character of the material.”

The fifth track, “Feuilles-Oh/Do Space Men Pass Dead Souls On Their Way To The Moon?” is the combination of a traditional Haitian folk song (used once before by Paul Simon in “Bridge Over Troubled Water”) and the tune of J.S. Bach's “Christmas Oratorio” Choral N°33, with lyrics by Art's betrothed, Linda Grossman. The end result is ethereal and childlike, discomforting, eerie, and as over-produced as a sophomore art project.

In his interview with Rolling Stone that October, Art was described as “nothing less than the graduate—a married, wealthy, 32-year-old man looking back with some amusement at his own headiness and with disappointment at his audience and his own generation. People are still, as he’d sung in his first million-seller, talking without speaking; hearing without listening.”

“The album, called ‘Angel Clare,’ adheres to the image of Art Garfunkel as the choirboy of pop music. It is churchy, with its echoes achieved inside the nearby Grace Cathedral, and with Garfunkel’s own multi-layered vocals at one point backed by a platoon of ten-year-old Chinese kids from the St. Mary’s Choir. Much of it is as full and beautiful as the best of S&G, and as meticulous and artful as the man himself. At the album-hearing (if not listening) party at Columbia, Garfunkel stood around, looking, as he often does, like a student teacher…”

“Garfunkel treated the interview with the same care—and caution—he has given his records. It was that meticulousness, in part, that had led to the dissolution of Simon & Garfunkel; now, he was being almost impossibly guarded in his responses to questions concerning his former partner and oldest friend. Over three days, we compiled some 60,000 words together, and few of them weren’t thought-out, and re-thought, and rephrased to Garfunkel’s own sense of inoffensive perfection. At one point, he said: ‘I don’t want to tell the whole story on my personal life because my personal life is more important than a full story.’”

“Two years ago [I had] been in group therapy… Very interesting experience… I’m thinking of going back… It was a hard time for me. I didn’t understand why certain things weren’t working… I had not begun my album yet. I didn’t know if I was going to do it. I had shaky confidence about my ability now to do my own thing. Didn’t know what my own thing was. I felt I had a minimal degree of insight into what is really going on with me and why I’m doing the things that I’m doing. And I felt that I was probably—although I didn’t feel any pain or anything—I felt I probably don’t even know what I really feel.”

“On the most obvious level I immediately found that there’s a tremendous value in verbalizing the issue. There are things I was in conflict over for years. But when I had to state the bottom line, I suddenly understood: Never underestimate people’s ability to not know when they’re in pain.”

In that moment, the interviewer flipped the conversation, asking Art to “Tell me more about this thing of yours — going around, catching people talking with a microphone hidden in a loaf of bread.” Art smiled as if remembering an old family holiday. He explained, “I don’t do it as a way of life. I did that device as part of a project to tape old people, because we wanted to have their sentiments as part of the theme in ‘Bookends.’ And I went out to try and record them. I went to old-age homes where I brought the mic right out and sat down and talked about things; and I also eavesdropped in Central Park, and I would take a long shotgun mic and hide it under my shoulder inside a loaf of French bread, and pick-up on conversations… I would just sort of walk in front of old couples. I just wanted to hear what they had to say. Two old ladies, seventy-two-years-old, meeting each other for lunch at two o’clock in the afternoon… 'What are they talking about?’ So I’d record; bring it home at night; listen to what they say.”

Laurie Bird was born on September 26, 1953, in Glen Cove, Long Island—a half-hour drive northeast from Kew Gardens Hills, to the affluent northern shore of Nassau County. Her mother died when she was three, leaving her father and two older brothers to raise her. Laurie’s father, an electrical engineer, was a stern and severe man; traditional, and exacting. He kept her on a short leash, which only inflamed the stubbornness she inherited from him.

Whenever his iron fist became too heavy, Laurie would run away from home—sometimes, into the city. She typically returned on her own but, finally exasperated with the runaround, her father forwent an impromptu search party and had an arrest warrant issued in her name. She was found on the beaches of Oyster Bay, overlooking Sagamore Hill, and her father had her institutionalized at a home for neglected girls.

Of course, she ran away from there just the same. At the age of fifteen, Laurie Bird hitchhiked across the country, onward to booming Los Angeles. The Summer of Love had been washed-out of the streets of LA, leaving freshly-poured asphalt to cook the city surface. In the sticky heat, beneath the shade of palms and steel, she finally found peace and stability: behind a camera, capturing forever a moment of beauty in a chaotic world.

Her still photographs of urban life caught the attention of Rudolph Wurlitzer, a screenwriter, who was researching Route 66 for a low-budget film. At the time, Wurlitzer was living in an LA motel, reading car magazines and palling with motorheads, grease monkeys, tuners, cruisers, and stoners. He met Laurie at a street race in the San Fernando Valley, and—after hearing her tales of hitchhiking across America—he recommended her to director Monte Hellman, who was looking for an actress to portray a hitchhiker.

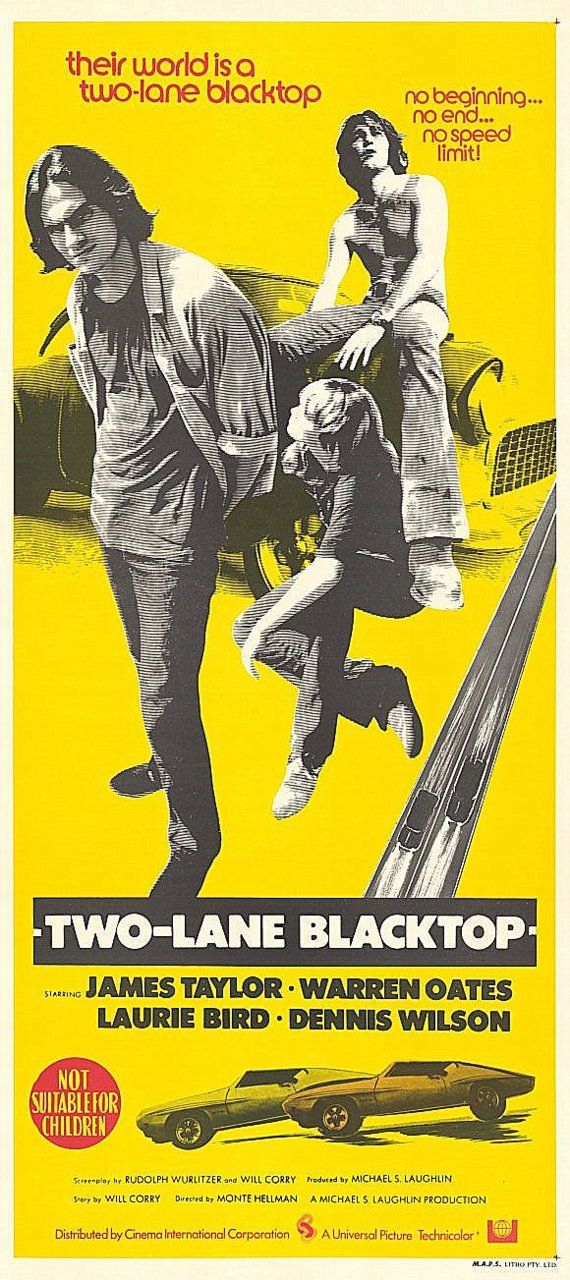

Laurie joined the cast of “Two-Lane Blacktop,” a New Hollywood-era road movie featuring best-selling folk-rocker James Taylor and Beach Boys drummer/ex-Manson Family mingler Dennis Wilson as “the Driver” and “the Mechanic,” respectively. Laurie undertook the role of “the Girl,” a hitchhiker picked-up in Arizona during the twosome’s easterly trek cross-country—via Route 66—in a matte-grey 1955 Chevy. The film had a meandering, consequence-based plot centered around early street-racing culture.

“Two-Lane Blacktop” was a cult success, rather than a commercial one, and went on to inspire the cross-country race known as “The Cannonball Run,” which subsequently inspired its own series of ensemble road/comedy movies in the 1980s. As a testament to pre-Interstate Highway America, “Two-Lane Blacktop” is remembered for its grainy, candid cinematography, its minimalist dialogue, and its prototypical ‘early 1970s’ existentialist vibe. The film—Laurie's first—has since been selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.

Laurie returned to her still photography for three years, until 1974, when Monte Hellman brought her back into the independent film world for the production of “Cockfighter.” Produced by B-movie kingpin Roger Corman (whose disciples included Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Jonathan Demme, and James Cameron), Monte Hellman’s “Odyssey”-adaptation about a gruff, grisled, and mute cockfighter failed to make back its budget.

Nevertheless, the audience it did have was impressed again by the natural ‘ingenue’ mystique of Laurie Bird. Film critic Michael Atkinson praised her performances, writing, “In two films, she made more of an impression—left more of a synaesthetic presence—than many actors do in a career.” She would appear in a film only once more, as Paul Simon’s girlfriend in Woody Allen’s 1977 romantic-comedy “Annie Hall.”

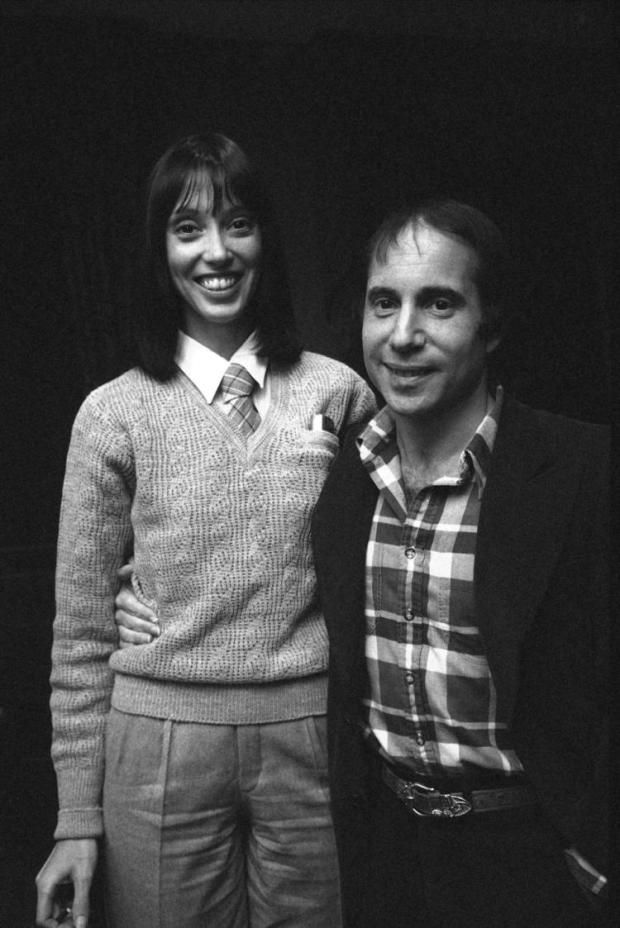

Laurie kept her camera active during the production of “Cockfighter,” photographing the set, cast, and crew. Director Monte Hellman took a particular shine to her (though he likely had been harboring one since “Two-Lane Blacktop”) and the two began dating. However, around this time, she met Art Garfunkel at a Hollywood party and began to date the singer instead. Technically, however—in the eyes of the State of Tennessee, the federal government, and Linda Grossman—Art was still married.

The Mistress Garfunkel and her suitor found themselves in a deeply romantic relationship. Art filed for divorce from Linda, and for five years he kept Laurie on a short leash—just as her father had—though Art saw no reason to restrain himself from travel, fanfare, and indulgence. Laurie lived in Art’s Manhattan apartment, like a pet, until she boldly left for the last time in 1979.

During an interview, later in life, Art seemed almost despondent when Laurie Bird was brought-up. “I asked myself constantly why I didn't marry her,” he said, tinged with remorse, “because surely she was the apple of my eye. She was everything I was looking for in a woman—but I was very hurt by my first marriage, so as far as marriage to Laurie was concerned, I was extra scared; I was heartbroken; it laid me low. I used to get very sad when the sun went down. The nights were very lonely for me.”

1975 was a groundbreaking year for television. “Wheel of Fortune” began broadcasting in the spring; the Jeffersons left “All in the Family” for their own sitcom; Ali fought Frazier in the HBO title fight “Thrilla in Manila;” and soap operas the world over switched from a half-hour format to a full-hour to keep pace with the competition.

Then, on October eleventh, legendary comedian George Carlin hosted the first episode of “Saturday Night Live.” Paul Simon hosted the show's second episode, a week later, in addition to performing a selection of songs, thereby beginning the show's tradition of featuring a musical guest alongside [or as] the host of each episode.

From the opening shot to the final seconds, Paul dominated most of the episode's airtime by performing selections from his upcoming solo album. He did, however, participate in a number of sketches, including the first appearance of the bee ensemble and a one-on-one basketball match between Long Island's 5’3” bard Paul Simon and Harlem's 6’8” Globetrotter Connie Hawkins.

In a twist that shocked national audiences, Paul took the stage mid-show and introduced “my friend, Art Garfunkel.” The studio audience roared to their feet. Together, S&G sang “My Little Town” and “The Boxer,” and Art performed “I Only Have Eyes For You,” which he was developing for a new album. At the end of their joint performance, Paul turned to his old partner and said, “It's good to sing with you again.”

A week after his ‘SNL’ appearance, Columbia released “Still Crazy After All These Years,” a ten-song album produced by Paul and the South African Phil Ramone. Four of the ten charted as singles: “Gone at Last” (#23), “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” (#1), the eponymous “Still Crazy After All These Years” (#40), and a reimagined “My Little Town” (#9). The steady incline of Paul's solo successes led to the single “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” topping the Billboard Hot 100, becoming his first and only single as a solo artist to achieve #1 on the pop charts.

His fourth studio album, “Still Crazy” was written and recorded in the shadow days of his divorce from Peggy Harper, lending a somber moodiness to the majority of the tracklist. The earliest ideas of the album originated one night, in the final months of his marriage, when he was taking a long shower. His depression had broken him into sobs, as he couldn't understand why he wasn't happy despite all the fortune that had come his way over the past decade. Then, a phrase popped into his head: “Still Crazy After All These Years.”

The album's eponymous song begins “I met my old lover / On the street last night. / She seemed so glad to see me. / I just smiled.” Many have believed the “old lover” represents either his recently-ex-wife Peggy or his long-ago muse Kathy Chitty. Some even suspect he might be referring to Art, which would be a little weird if the story were interpreted literally. The commentary Paul imparts with “Still Crazy After All These Years” is the beauty of nostalgia and how, as it fades, it is replaced with grief—namely being loneliness, self-loathing, and regret.

“Still Crazy After All These Years” won the Grammy Awards for ‘Album of the Year’ and ‘Best Male Pop Vocal Performance.’ In his acceptance speech for the former, Paul expressed his gratitude to Stevie Wonder—facetiously—for not releasing an album that year, as Mr. Wonder had won ‘Best Album’ the past two years running, with ‘Innervisions’ and ‘Fulfillingness' First Finale.’ Seems Mr. Wonder had spent ‘75 building a repertoire, as he took 'Best Album’ again the following year (1977) for the double-album ‘Songs in the Key of Life.’

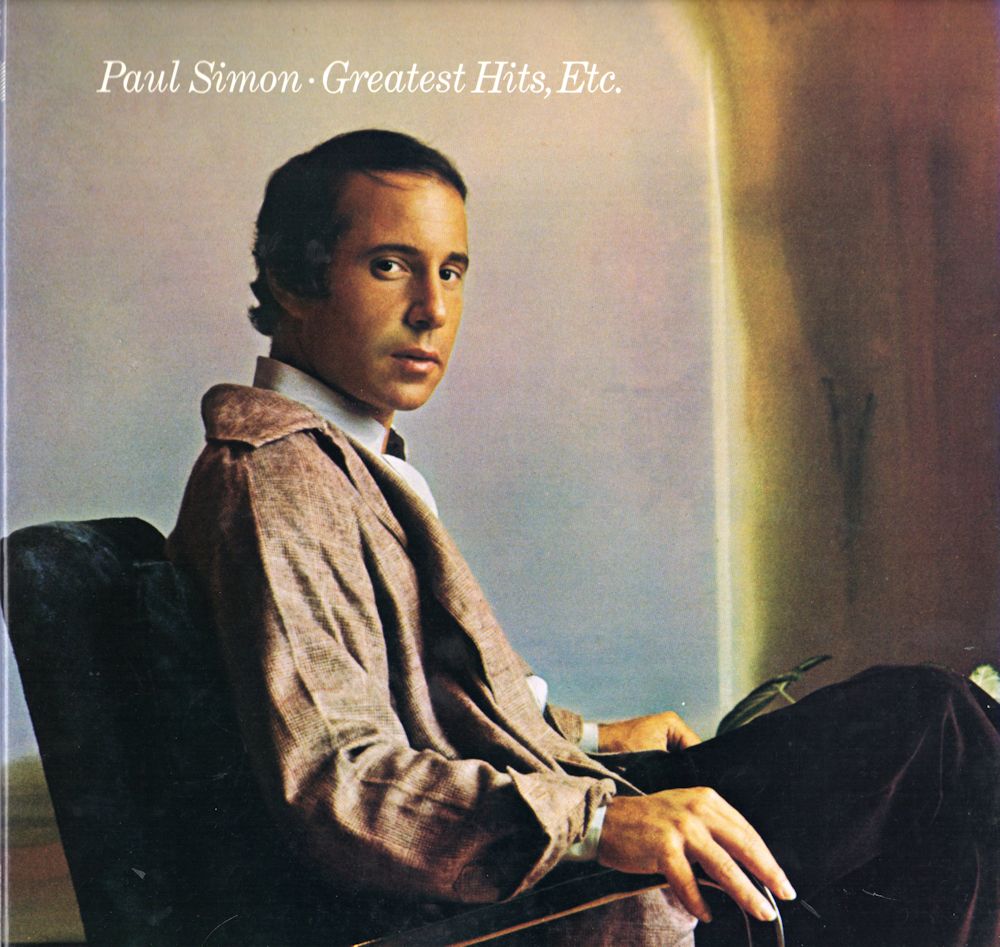

In November of ‘77, Columbia released “Greatest Hits, Etc.” — the first ‘greatest hits’ album of Paul Simon's solo material. Woody Allen's “Annie Hall” also premiered that year, featuring Laurie Bird as Paul Simon’s girlfriend. In reality, Laurie was dating Art Garfunkel, and Paul Simon was dating Shelley Duvall, of “The Shining.”

On the Thanksgiving episode of ‘SNL,’ in 1976, Paul appeared beside his friend George Harrison as the musical guest to perform “Here Comes the Sun” and “Homeward Bound” together. Paul also performed “Still Crazy After All These Years” while dressed as a turkey, but halfway through the song he feigned embarrassment and stopped the song to walk offstage. The show's creator (and his dear friend) Lorne Michaels stood by to lift his spirits, but Paul griped, calling the whole scenario “humiliating.” The audience lapped it up.

Paul went on to appear as the host and/or musical guest of ‘SNL’ fourteen times. In an episode hosted by Justin Timberlake, in 2013, he made a cameo appearance as a member of “the Five-Timers Club,” which he had joined back in May 10, 1986, becoming its fourth honorary member. In one of this episode's skits, Paul portrayed himself, waiting in line at the cinema with a friend. He recounts a slew of details about moments he's shared with some of the pedestrians milling around him—but, when Art Garfunkel nears, Paul can't seem to remember him, no matter how many bones his old friend throws.

In 2001, at his friend Lorne Michaels’ request, Paul made an appearance in the show's first episode to follow the collapse of the Twin Towers. The nation was in mourning, though the studio was in a particular state of shellshock that night, given how ‘SNL’ is filmed in Manhattan, and the cast, crew, and audience were all locals. After an opening statement by Mayor Giuliani, Paul performed “The Boxer” for and in honor of the city's first responders.

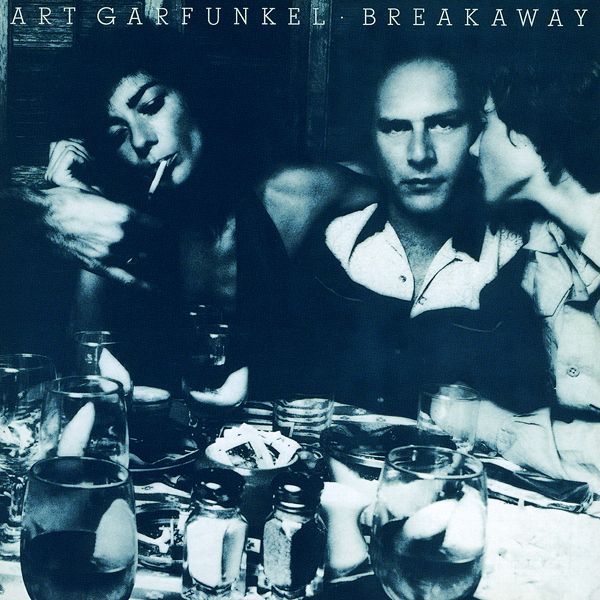

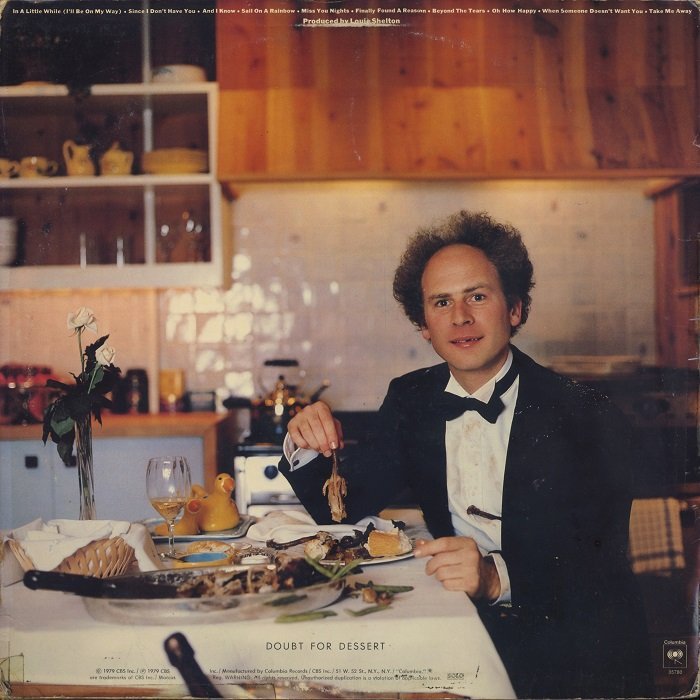

In 1975, Columbia released Art Garfunkel's “Breakaway” album, including a re-release of “My Little Town” and the singles “I Only Have Eyes For You,” “Rag Doll,” “99 Miles From LA,” “Disney Girls,” and “Looking for the Right One,” featuring 50% of Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young. The album received mixed reviews and largely fell by the wayside, though lead single “I Only Have Eyes For You” did reach #1 in the UK for a hot minute (peaking at #18 in the US) and the title track briefly reached #2 on the Canadian Adult Contemporary chart—kept from the top only by Paul Simon’s “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover.”