On October 24, 1966, Columbia Records released Simon & Garfunkel’s third studio album, “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme.” Instead of the three weeks they had to produce “Sounds of Silence,” the duo had three months to perfect the prose, arrangement, and instrumentation of twelve new songs. The tracklist begins with a traditional folk song, remixed in counterpoint, and ends with a sound collage blending the Christmas Carol “Silent Night” with the 7 O’Clock News bulletin of August 3, 1966.

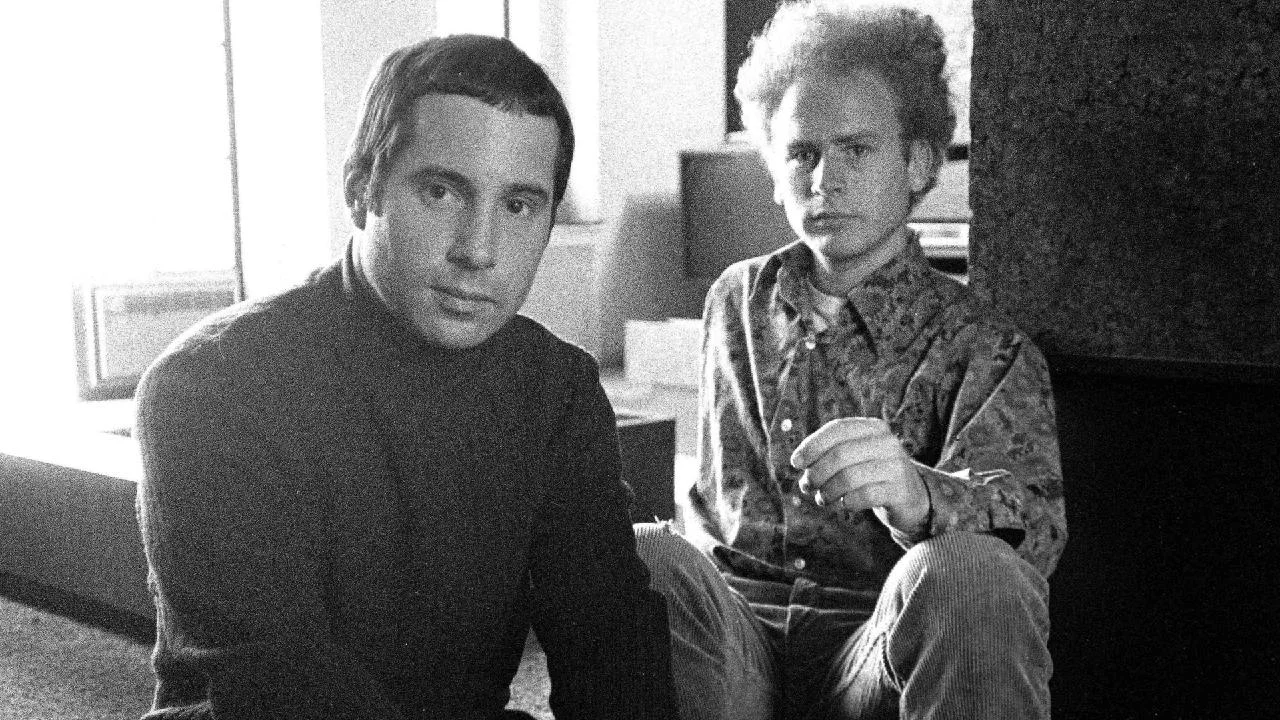

Art Garfunkel regarded “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme” as the dawn of the rest of his life. “After the three weeks it took us to make the ‘Sounds of Silence’ album, and getting together with Mort Lewis as a manager—early ’66—and beginning to do some road work that fall, we started to make our next album the way we wanted to make it. From that point on it became Roy and Paul and me. In many ways I thought that was the beginning of our record career.”

In the months following their third album, representatives of corporate brands worldwide sought them out, like the belle of the ball or the prized cow, ready to be milked. Art recalled one such event, where his manager Mort Lewis said, “‘They offered us $25,000 for a Coke commercial; I think you could get more if you wanted to do it.’ ‘How much more?’ I would say. ‘Well, maybe we could get $50,000.’ ‘Well, let’s see if they’ll go 50.’ Then they’d say 50, and we’d say, ‘Nah,’ but we wanted to know—would they pay 50? We wanted to know.”

— Chapter III —

Bridges & Waters

“Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme” was largely composed of the acoustic songs Paul had written while in England, when he still had his muse. These included the Garfunkel-helmed “For Emily, Whenever I May Find Her,” heavy-hearted lead single “Homeward Bound,” and the highfalutin swan song for a marriage, “The Dangling Conversation.” In spite of the latter’s performance, the album reached #4 on Billboard’s Pop Album chart, onward to become certified triple platinum (selling 3,000,000+ copies).

As Nick Wanserski wrote for the A.V. Club, “The Dangling Conversation” is narrated from “the point of view of one half of a cold, intellectual couple who have lost their connection to each other.” They sit in the same room, reading separate poetry books at different paces, bathed in the light of the same afternoon sun — physically close and temporally syncopated, but emotionally disconnected and drained of passion. “Couched in our indifference, like shells upon the shore,” they sing in the second stanza.

“As overwrought as the lyrics may be,” Wanserski writes, “they succeed in capturing the sharp moment of realization that a relationship is over and has been for some time; the inertia of fear and habit no longer sufficient to resist the sad truth.” The composition has aged poorly, giving much of its backbone to orchestral strings and a Wagneresque harp. As Wanserski points out, though, on its own accord, the last stanza summarizes the pathos of the piece as a “sad eulogy” to a marriage long-decayed: “And how the room is softly faded / And I only kiss your shadow / I cannot feel your hand / You’re a stranger now unto me.”

“Between the ages of 15 and 22,” Paul stated in a 1972 interview with the Rolling Stone, “I had made only one very minor hit at the age of fifteen and then [followed by] flops. So I expected everything to be a flop. I was utterly amazed that ‘The Sound of Silence’ was a big hit. More amazed that ‘Homeward Bound’ was a big hit. By the time ‘I Am a Rock’ was a big hit, I started to think, ‘Now I’m making hits,’ so now I got amazed when ‘The Dangling Conversation’ wasn’t a big hit. Why it wasn’t a big hit is hard to know. It probably wasn’t as good a song. It was too heavy.”

The album maintained momentum throughout 1967 and, in early 1968, “Scarborough Fair/Canticle” was released as a single. This was a year and a half after the album came out (another uncommon music industry practice at the time) but, following the release of Mike Nichols’ “The Graduate” in 1967, it peaked in popularity. Columbia capitalized on the moment and “Scarborough Fair/Canticle” reached #11 on Billboard’s Hot 100.

This song is a rarity in popular music, as it’s arranged in counterpoint—the art of weaving two preexisting melodies into a single composition. Ergo, “Scarborough Fair/Canticle” is the conjunction of a traditional English folk ballad “Scarborough Fair” and the poem “Canticle,” a Garfunkel-rewrite of the anti-war track “Side of a Hill” from Paul Simon’s “Songbook” album. It was one of few lyrical contributions Art Garfunkel would make during the twosome’s foray. Until he went solo, Art wrote “very little,” specifying, “I wrote an occasional line for some of Paul’s songs.”

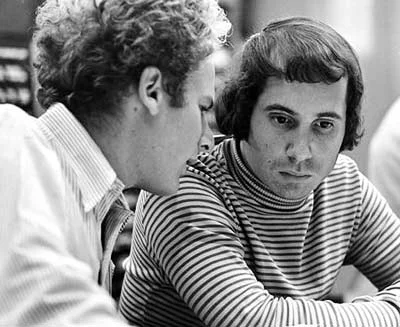

“I mean, it’s really ASCAP or BMI that labels that as the one song I did it on. When you do it for three lines’ worth, you’re not a songwriter. You do it sixteen lines’ worth, you’re a songwriter.” Given this, Art was more often credited as an “arranger” for his input, namely because, “I think, Paul objected to the idea of being left out. Coming up with the line that a string player would play is something that Paul did as well. I might be the one [in more cases] to pin down the specific line and show the musicians what to play, note for note.”

In his 1972 interview, Paul disputed the popular belief that Art Garfunkel made no creative decisions in their relationship, and that “arranger” was a bullshit title. “Anybody who knows anything would know that was a fabrication; how can one guy write the songs and the other guy do the arranging?” In his eyes, it was a team effort. Art avoided the accreditation altogether, saying, “I don’t know what people think arranging means. I think of myself as a ‘record-maker.’ When I’m in the studio, I take the song and try to fill out tracks…”

The counterpoint technique was another contribution of Art’s, inspired by the harmonies he heard as a child. “I wrote the counter-melody [for] ‘Scarborough Fair.’ … It came out of my ability to sing along to…the Everly Brothers. [In my youth] I heard notes held, and harmonies, and great articulation and diction, and a very interesting sound in two voices. I had a musical background that taught me a little about chord structure so I could feel the chordal underpinning that makes up a song. If I knew the song from having heard it once, I could feel the next coming chord [and] I’d know where I was as if I could graphically see the note. I was singing in relation to the melody whether it was a third higher or a fourth below. I’d feel the new chord coming up and know what my choices were; what would blend-in. Then the next step was shaping the line; parallel movement; countermovement. By the time Paul and I were recording in the Sixties I could do all that.”

When asked again, more to the point, if he believes his role has been historically undervalued, Art replied, “Absolutely,” adding, decades later, “Sometimes I think I used to get away with murder because I'm a special singer.”

In addition to having quadruple the amount of time to record “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme,” compared to the rush-job of their previous album, Paul demanded complete control of the studio sessions. Roy Halee would mix every recording, as expected, but there would be no Tom Wilson standing over his shoulder, and there would be no Clive Davis on the phone, demanding for punchier “hit single” material.

Columbia was eager to please. They bestowed rare creative freedoms to Simon, Garfunkel, and Halee—the folkish braintrust—with an unprecedented budget of $30,000. (Equating to nearly a quarter of a million dollars, given USD inflation at the time of this article.) A portion of this went towards Columbia’s purchasing of an eight-track recording system, at Simon & Garfunkel’s request. Roy Halee asserted it to be easier to overdub Simon’s guitar separately from the duo’s vocal takes, so as to have a cleaner mix. Such precision of the braintrust led to Clive Davis commenting, to Paul Simon, “Boy—you really take a lot of time to make records.”

The result of their perfectionism was an album composed of twelve very distinct songs. Paul had felt “alienated” during the writing process, as he was touring on another of Columbia’s promotional showcases, marketing “Sounds of Silence” in sold-out concerts at college campuses across the country. He preferred things “to be familiar” when songwriting, hence these “alienated” emotions lending themselves to the melancholic sound of songs like “Scarborough Fair/Canticle,” “Homeward Bound,” and “The Dangling Conversation.”

Other flavors thought of the album included “poetic” and “weird.” The frenzy of fame and the subsequent loss of his muse had worsened Paul’s anxiety and depression. He suffered from an inferiority complex against his perception of greatness. With such high-expectations, nothing he produced was ever good enough to satisfy him, and so he wrote, and recorded, and sang, ad infinitum—and though the limelight of performance convinced him otherwise, his satisfaction lasted only as long as the applause.

At a concert in Portland, Oregon, in May of 2018, Paul briefly forgot the lyrics of a song, mid-performance. This had never happened to him before. He was, to be fair, 76-years-old and singing a 28-year-old song—one of hundreds of songs he’s memorized over the years; he refuses to use a teleprompter, unlike the majority of aging songsters—yet he could not help himself from apologizing profusely to the audience.

After finishing the song, Paul told the crowd, “I’m going to penalize myself. I’m going to sing one of my songs that I loathe.” He switched to an acoustic guitar and sighed, saying, “This will teach me, because I just— I hate this song.” And so began a short rendition of “The 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin’ Groovy),” which he had conceived during a frustrating and claustrophobic layover between concerts; walking through Queens, across the 59th Street bridge, looking for inspiration before recording “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme.”

Their second album of 1966, “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme” rocketed Simon & Garfunkel to celebrity-status; to become peers to the prestigious rock’n’rollers they once admired. Both were only 25 years old yet their (re: Paul’s) past decade of being knee-deep in the industry had earned the duo a coveted license for ‘artistic freedom.’

“Being in the studio and making records in the sixties,” Art told Peter Fornatale, “I can tell you, it was very uncorporate. It was highly spirited. It was kids at play. It was just a wonder that you were allowed to do this; that two middle-class kids can sign a contract, rehearse, and get their talent into the studio, and then find that the entire distribution network is waiting to put-out their products. It was wonderfully simple, sincere, and un-cynical.”

“For a long time, I had a real dislike for all aspects of the recording business. The trappings held nothing for me—the fan structure, all that” — but, in 1966, Art Garfunkel’s opinions on fame and glory were undergoing a metamorphosis. In his memoir “What Is It All But Luminous,” he wrote of becoming the famous double-act, “taking the world by storm, ruling the pop charts,” and “touring; sex-for-thrills on the road,” all while strategically devaluing himself; posturing as a gifted intellectual: “not being a natural performer, but more a thinker…”

As a boy, surely, Art did not enjoy the limelight. “To be out—and involved—is not my natural state. When I was in high school, I withdrew a lot. My friends were reduced to one or two. I read a lot, and I played the game of ‘doing well in school’—maybe by default… I could never accept myself as ‘one of the gang.’ Everything I did was cast in the image and perspective of the outsider. I became a sociologist in spirit; an incessant observer,” forever learning, calculating, and posturing. Even without looking too deeply, one can see in his eyes the gears turning; the machinations of a perpetual scheme to conceal his ego.

While Art lived to be seen, Paul Simon lived to be heard. Beneath the limelight was the only place he felt comfortable; where he felt he belonged, and mattered. “I always like to perform, given the proper circumstances—a full house and good sound. I’m in complete control, and I get the pleasure of making music with someone else. When I’m on the stage, I’m up—and happy. I feel like laughing.”

“I’m continually surprised at the response. I never thought we would affect people so much. It’s not so much the epiphany for them as the relief. People fear that they’re alone. They listen, and they feel what I feel, and they say, ‘I’m not alone!’ The basic approach on the stage is to exaggerate things and make them larger than life. But we’re in a time when so much is larger than life. So [Art and I] take an uncommon approach. I feel you can be effective by being the same size as life, or smaller.”

“I’ve got more relaxed onstage,” Art interjected. “It’s the impetus of Paul. And singing for large groups increases one’s sense of power.” He inhaled the room. Paul then submitted to the reporter, as if in pointed commentary on his partner, that “[such] an interview is a real ego trip. You have to remember that your opinion is not important—it’s merely of interest.”

All albums are predestined to fall from the charts, but a rare few live-on in the annals of music history. Rolling Stone listed “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme” as #202 on their list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. Andrew Gilbert included it in his ‘1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die,’ citing this as “their first great album,” imparting “a sense of impending doom” alongside Paul Simon’s “insistence on emotional connection.” Peter Fornatale noted, of Paul Simon’s lyricism, “Few others have come close to the intelligence, beauty, variety, creativity, and craftsmanship that [this album] captured.”

The BBC’s Andy Fyfe wrote that “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme” was a “substantial [milestone] in folk rock’s evolution” and has since sustained “a sense of timelessness:” though its composition had “reflected the social upheaval of the mid-60s” its “boldest themes [are] still worryingly pertinent today.” Such visual poetry, commenting on “youthful exuberance and alienation,” has resonated with “older, more thoughtful high-school students and legions of college audiences across generations.”

In a 1967 New Yorker interview, Paul Simon expressed he was not intending to make a masterpiece. He said that, “After ‘Sounds of Silence,’ the Simon-and-Garfunkel thing just kept going. There was no time to get off. Finally, I said, ‘This is what I want to do, and I want to do it as well as I possibly can.’ I’m stimulated to go forward. If I fail, I’ve got so many ego points I’ll never be as paranoid as I was. So—straight ahead, and work!” Grind away your insecurities with proliferation! Become the master of your fate! Only then, “When you find you’re in control of your destiny, [is it] fun. You do things you want to do.”

The Sixties were an interesting time for cinema. Hollywood was moving away from classic studio productions—think “Stagecoach,” “Footlight Parade,” “Ben-Hur,” “Casablanca,” “Singin’ in the Rain,” “Mary Poppins,” “Cleopatra,” “Lawrence of Arabia,” “The Longest Day,” “West Side Story”—of monstrous budgets, contract players, cinerama lenses, and big-names on big-sets with big-scenes for big-stories. Gone were those days by 1967, at the dawn of the “New Hollywood” era.

Twas a renaissance in filmmaking; the beginnings of a new breed of filmmaker, wherein the director—a youthful auteur, raised on movies and television as opposed to theatre and radio—held the creative authority of a film more so than a producer. Such a bold practice came to rule the Seventies but, with a few big busts in the early Eighties, Hollywood morphed back into a studio-run system, producing blockbusters and Oscar-fodder.

From 1967 to 1982, though, the New Wave washed over American cinema and gave us such now-classic films as “In the Heat of the Night;” “Bonnie and Clyde;” “The Graduate;” “Cool Hand Luke;” “The Dirty Dozen;” “2001: A Space Odyssey;” “Planet of the Apes;” “Rosemary's Baby;” “Bullitt;” “Night of the Living Dead;” “Easy Rider;” “Midnight Cowboy;” “The Wild Bunch;” “Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid;” “They Shoot Horses, Don't They?;” “Catch-22;” “MASH;” “Patton;” “Carnal Knowledge;” “Two-Lane Blacktop;” “The French Connection;” “A Clockwork Orange;” “Dirty Harry;” “Harold and Maude;” “The Godfather;” “American Graffiti;” “The Friends of Eddie Coyle;” “Chinatown;” “The Conversation;” “Blazing Saddles;” “Young Frankenstein;” “One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest;” “Dog Day Afternoon;” “Jaws;” “Barry Lyndon;” “All the President's Men;” “Network;” “Rocky;” “Taxi Driver;” “Annie Hall;” “Close Encounters of the Third Kind;” “Eraserhead;” “Saturday Night Fever;” “Star Wars;” “National Lampoon's Animal House;” “Halloween;” “Alien;” “Apocalypse Now;” “Airplane!;” “Raging Bull;” “Raiders of the Lost Ark;” “Mad Max 2;” “The Thing;” “Blade Runner;” “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial;” and subsequently all of these people.

Narrative norms were discarded in favor of uncertainty, melancholia, and discomfort; noble conservative themes were reborn in perversion, social integration, and moral ambiguity; stylistic standards gave way to conflict irresolution, suspense, subtlety, and nonlinear storytelling. It was an era of upheaval; of rebellion; of “anything goes.”

Many academics consider 1967 to be the most groundbreaking year in film history, as it yielded a great bounty on the doormat of the New Hollywood revolution. Such ingenious, taboo-breaking films included “Guess Who's Coming to Dinner” and “In the Heat of the Night” (both critical installments in cultural progression via the silver screen) and “Bonnie and Clyde,” “The Graduate,” and “Cool Hand Luke” (all stylistic pioneers in visually expressing love, cruelty, and conflict). Together, these five clinched the main categories of the Academy Awards that year, with Best Director going to Mike Nichols for “The Graduate,” Best Actress going to Katharine Hepburn for “Guess Who's Coming to Dinner,” Best Supporting Actress going to Estelle Parsons for “Bonnie and Clyde,” Best Supporting Actor going to George Kennedy for “Cool Hand Luke,” and Best Actor going to Rod Steiger for “In the Heat of the Night,” which also won Best Picture.

In 1967, Jack Nicholson’s LSD-chronicle “The Trip” outperformed Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton’s stage-to-screen “The Taming of the Shrew” at the box office; Audrey Hepburn’s quirky thriller “Wait Until Dark” busted the original animalinguist “Doctor Dolittle;” still-alive Sharon Tate-helmed salacious pastiche “Valley of the Dolls” wiped the floor with Julie Andrews/Mary Tyler Moore/Carol Channing’s future-theatre-bait vessel “Thoroughly Modern Millie;” and “The Jungle Book” (Walt Disney’s last animated film before he was cryogenically frozen, thus sealing the fate of his damned corporation) was thrown off the box office podium by an intimately-shot, grimly-realistic tale of collegiate lust and angst, “The Graduate.”

Released December 21, 1967, “The Graduate” starred a fledgling Dustin Hoffman in his silver screen debut opposite Katharine Ross and the legendary Anne Bancroft. In short, it tells the story of a disillusioned college graduate who finds himself “torn between his older lover and her daughter.” Dustin portrays Benjamin Braddock, a representative of innocence as it’s seduced, exploited, corrupted, and betrayed—thematically analogous of America’s once-trusted institutions in their discreditation and corruption following the assassination of JFK, the surge of the Civil Rights movement, and the escalation of the Vietnam War. (It’s a big to-do.)

When director Mike Nichols and his editor were in post-production, splicing together reels and scenes, they used “The Sound of Silence” as one of their temp tracks — an audio string used to synch shots and establish tone for a composer to later emulate in an original score. Temp tracks are borrowed from old classical works or sourced from preexisting scores. Sometimes, an established song from the real world is used as a placeholder.

Nowadays, balancing a movie with a soundtrack of pop/established songs or their ethereal/counter-genre covers is a standard practice in indie and blockbuster films alike. This did not happen in 1967; it was neither a practice nor a consideration for practice. But after watching and re-watching his reel synced to “The Sound of Silence,” Mike Nichols realized he could neither create nor discover a better substitute. So, he petitioned his producer to purchase the rights to Simon & Garfunkel's first anthem. (Such unusual yet incredible decisions during the production of this film are what ultimately earned him the Oscar for Best Director.)

While Paul and Art were in the studio, finalizing “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme,” they put-out a single called “A Hazy Shade of Winter.” It peaked at #13 nationally, later to be revived in 1987 as a killer rock anthem by the Bangles. S&G released “At the Zoo” in early 1967—another single—but, by that point, Paul had run his well dry.

“I'm not interested in singles anymore,” he told an interviewer. He was intent on putting out another album—this time, a concept album; a whole album of worth—but he was in the pits with writer's block. His muses had come and gone.

S&G had nothing slated for 1967—a cause for worry among Clive Davis and the other executives at Columbia. Songsters in this era were expected to produce at least two albums a year until they ran out of milk. Having nothing to publish in 1967 made newborn-stars Simon & Garfunkel look like bad bets and old rice.

Clive took fondly to barking-up Paul's tree about his supposed laziness. Clive was of the old school of thought: musicians recycle current sounds into new sounds and then release singles for the radio, ad infinitum, with readied and flexible mimicry for whenever some jagoff decides to stand apart from the herd. And the industry chugs along.

Paul, however, was of the new school of thought — the perpetually-new school that yearns for innovation, pushing boundaries, and staying ahead of the pack hounds. As came the New Breed of Hollywood, so came the New Breed of the airwaves: those who wanted to make more than singles. Particularly, those who wanted an album to exist as an entity; as a complex object of singular purpose, designed to be enjoyed in its entirety. (Think, Pink Floyd's “Dark Side of the Moon” from 1973.)

The first true “concept albums” were made in the dust bowl era; acoustic and folksy, from the likes of Woody Guthrie. In the 1960s, as the cultural idea of “intentional albums” grew, troubled troubadour Brian Wilson locked himself in a recording studio and conceived “Pet Sounds” — a Beach Boys vinyl released in the spring of 1966. The Beatles—aware of Brian Wilson's endeavor across the pond, and itching to take the throne back from Simon & Garfunkel after “Sounds of Silence” stormed the world—recorded and released the album “Revolver” at the end of summer.

Both “Pet Sounds” and “Revolver” were designed to be an ‘experience’ rather than a ‘compilation of singles.’ (You might find it hard to believe that, prior to this moment, albums were rarely themed. Though, in our modern era of streaming and digital downloads, a “singles-dominated music industry” might seem standard to those too young to recognize or imagine an album-oriented America.)

Subsequently inspired by Brian Wilson and the Beatles, Paul Simon sought to create something holistic and meaningful. Clive Davis may have thought Paul had churned out those past two records, but the singles they were composed of had been written across the previous half-decade, during a period of inspiration with Kathy Chitty. This time, Paul was starting with a blank canvas, and he wanted to use every inch of fabric to paint something powerful.

In England, the Moody Blues were doing the same, except they already had the concept in mind: an ordinary day, unfolding sonically. Beginning with the dawn, the album would go on through the workday, lunchtime, rush hour, and into the evening with the single “Nights in White Satin.” It was all instrumental-oriented, so as to duplicate the sounds of daily life and evoke the energy of the hour. Modern rock surrendered itself to an orchestra, thereby producing what many agree to be the first example of progressive rock.

Released in November of 1967, “Days of Future Passed” fared well without fireworks. As with anything revolutionary, it took the world a few years to warm-up to the idea of progressive rock. (Five years, to be exact.) Today, “Days of Future Passed” is hailed by critics and academics alike as one of the best albums of all time.

In his analytical tome of this groundbreaking musical era, Prof. Bill Martin wrote, “In discussions of progressive rock, the idea of the ‘concept album’ is mentioned frequently [and] if this term refers to albums that have thematic unity and development throughout, then in reality there are probably fewer concept albums than one might first think… However, if we instead stretch the definition a bit, to where the album is the concept, then it is clear that progressive rock is entirely a music of concept albums,” whose mighty wave crashed in the late Sixties, with records like 'Pet Sounds,’ 'Revolver,’ 'Days of Future Passed,’ and 'Bookends.’ Then, “in the wake of these albums, many rock musicians took up ‘the complete album approach.’”

In 1967, however—as with the Moody Blues—the mainstream recording industry was not eager to dabble in “concept album” territory. Executives wanted singles, because singles made it to the airwaves, and from the airwaves came the revenue. Clive Davis sat Paul Simon down a number of times to convince him to abandon his pursuit of “artistic integrity” and to instead “make music.”

Paul hated the “suits” at the label. They were the studio equivalent of a guido giving forty seconds of unrequited grind-time to every girl at a club until one flashes him bedroom eyes and leads him out the back door. At one particular sit-down with Clive Davis, Paul covertly recorded the communique to tape and he played it back to Artie in privacy. The twosome laughed together at the “fatherly insistence” Clive had in his well-rehearsed plea for their haste.

To put it simply, Clive Davis had no effect on Paul's creative process. The songs Columbia wanted could not be pulled from thin-air, and Paul conceded no force in imagining them. Clive returned to his office, empty-handed and morose—and, to his surprise, a man was waiting there for him.

Wearing a convincing wig atop a head that escaped Nazi Germany, the young man thumbed his collar and rose from the leather couch. He appeared urbane in demeanor though with the physical features of a Chicagoan. He was barely thirty years old and yet he was one trophy away from an EGOT. Of course, Clive didn't know any of this yet, and he asked the man if there was maybe a scheduled meeting he'd forgotten.

The man chuckled and apologized; the secretary had let him in, he said, extending his hand. He introduced himself as Mike Nichols, and he was making a movie.

“I’d been listening to their album every morning in the shower before I’d go to work,” Nichols later explained, “and then one morning it just hit me: ‘Schmuck! This is your soundtrack!’” He took the track to his editor, “and it was like, ‘Holy shit, this fits exactly and it’s twice as powerful!’ It’s one of those miraculous moments you get when you’re making a movie, where everything somehow comes together. It’s better than sex,” he said, with a pause. “Okay, maybe not better, but it’s indescribably fantastic.”

Mike Nichols had found himself listening to “Sounds of Silence” day-in and day-out during his filming of “The Graduate.” Upon realizing his obsession had prophesied a purpose, he flew to Manhattan and stole a meeting with Clive Davis to negotiate the film rights to a bevy of S&G songs—and Clive was all too eager to accommodate.

This was the perfect opportunity to squeeze an album out of Paul Simon for 1967. Furthermore, if attached to an acclaimed director like Mike Nichols, an S&G soundtrack would assuredly sell gangbusters. Clive Davis pitched Paul and Art on the idea, calling it “a match made in heaven.” Art was receptive to the idea but Paul had his reservations; he believed contributing to movie soundtracks was a form of “selling out.”

Nichols committed to proving otherwise. He gave Paul a copy of the script and, with his biting wit, convinced Paul that if ever there were a movie worth gambling artistic integrity over it would be “The Graduate.” The vision Nichols had for his film—something unlike typical Hollywood fare—ultimately inspired Paul to agree. A contract was drawn, to award Paul $25,000 for the inclusion of four songs in the final cut of “The Graduate.”

A few weeks passed and Paul submitted two new songs to producers—”Punky’s Dilemma” and “Overs”—but Mike Nichols didn’t feel they fit the narrative. He asked Paul for something else but, as Art later recalled, “Paul didn’t have anything… So Mike was living with ‘April Come She Will,’ ‘Sound of Silence,’ and ‘Scarborough Fair’ as placeholders, learning to love them just as they were in their places.” These three were sufficient but Nichols still needed one other to complete the film and uphold the contract. “So he told Paul to give him one song for when Dustin is racing down the west coast to break-up the impending marriage of his girlfriend, Elaine. It needed to be up-tempo. Paul had the rhythm, but not the song.”

“And there, in the sound stage, I said to Mike, ‘You know, Paul is working on a song called ‘Mrs. Roosevelt.’’ Mike said, ‘Do you know how right that could be if we just changed the name? The syllables are perfect.’ So Paul sung, ‘So here’s to you, Mrs. Roosevelt,’ and I started harmonizing. When I harmonize with Paul, it falls into place—[such is] the history of Simon & Garfunkel—so Mike heard the duet, bought the whole idea, but of using ‘Mrs. Robinson’ instead of ‘Mrs. Roosevelt.’ There was no verse yet, so in the movie you hear: ‘doo, doo doo-doo doo doo, doo doo-doo doo doo-doo-doo’ — that’s called ‘a song not written yet.’”

The song so far, as Paul had figured, was a tribute to Eleanor Roosevelt and to the days of old; of American heroes and moral government. The verses were written with an image in mind, of Eleanor going to a sanitorium for tuberculosis treatment—sometime between her car crash in 1960 and her death in 1962—as a psychiatrist is preparing her for the stay. “We'd like to know a little bit about you for our files. / We'd like to help you learn to help yourself. / Look around you, all you see are sympathetic eyes. / Stroll around the grounds until you feel at home.”

It’s a rough draft of the chorus that appears in the film, with Eleanor Roosevelt substituted for Anne Bancroft's character. Paul then rewrote the chorus—again—for “Bookends,” resulting in “And here's to you, Mrs. Robinson / Jesus loves you more than you will know. / Whoa, whoa, whoa. // God bless you please, Mrs. Robinson / Heaven holds a place for those who pray. / Hey, hey, hey. / Hey, hey, hey.”

The single “Mrs. Robinson” was released in April of 1968, three months after the film and on to become #1 on Billboard’s Hot 100. The film’s soundtrack rode Mrs. Robinson’s coattails to #1 on the Billboard 200 album chart—a position held for over six straight weeks, until it was unseated by Simon & Garfunkel’s next album, “Bookends,” which featured “Mrs. Robinson” as its tenth track. At the 1969 Grammy Awards, it took ‘Record of the Year’ (the first-ever rock song to do so) as well as ‘Best Contemporary-Pop Performance by a Vocal Duo or Group.’

Unfortunately it was deemed ineligible for a ‘Best Original Song’ Oscar nomination, as it had not been written exclusively for the film. Had Paul argued that only the backbone of “Mrs. Robinson” existed prior to his contract with the studio, there is an extremely good chance “The Graduate” would’ve won more than ‘Best Director’ (a quirky achievement not since duplicated: winning ‘Best Director’ and nothing else) as Paul Simon’s classic hit would have easily out-bid “Talk to the Animals” from fucking “Doctor Dolittle” as the ‘Best Original Song’ of 1967.

But Paul Simon did not challenge the Academy; no, it seemed he was preoccupied with the crafting of his next masterpiece — and Art Garfunkel was there, too.

I’m sure by this point—halfway through a five-part series on Simon & Garfunkel—you’re wondering, “Why is so much of this story about Paul Simon? Where’s all the Garfunkel? We want more Garfunkel!” Well, dear reader, you’re likely the first person since time immemorial to request more Garfunkel. Might I recall, the story is “And Garfunkel: Life in the Shadow of the Bard” — the tale of a human windchime as he curdles like lemon twist in the milk of a braying legend, and these youthful years are the stones tread upon towards his euphonious Valhalla.

The life of Art Garfunkel begins in Forest Hills, 1941, but the STORY of Art Garfunkel begins with the end; rather, the “Bookend.” Until this point, Art Garfunkel had happily taken the sidecar on their musical motorcycle ride. He was shy, originally, but the glow of adulation and the prestige of his “extremely rare voice-type” spoiled him. Time spent in the limelight tainted his personality, riddling him with ego; inflating his perception of self-worth until he bled confidence. The sweet boy from Queens was becoming bitter, arrogant, and cold.

During the recording of “Bookends,” the first veins of conceit began to snake beneath Art’s skin. The voice of an angel learned to bark, and soon it would learn to bite. The clock was ticking on Simon & Garfunkel, as the fissures of disharmony wove beyond dulcet tones and planted seeds of disdain within; within those whose sound had only been loved in union; within those hearts of brothers forever bound by conquest, by pain, by influence, and by name.

Simon & Garfunkel released “Bookends,” their fourth studio album, on April 3, 1968—not even 24 hours before the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. The nation descended into outrage and mourning, and “Bookends” was there to comfort the American people, much like “Sounds of Silence” had in the wake of JFK’s untimely death. Peter Fornatale referred to the album as “comfort food,” and America licked the bowl clean. As soon as it was eligible, “Bookends” shot to the top of the Billboard Pop Album Chart and remained there steadily for seven weeks, with a charting presence for sixty-six.

Produced by Roy Halee, this concept album expounded on a lifetime—the journey we all walk, from youth to death—and the themes explored were largely those of Paul Simon’s previous work—naivete, disillusionment, mortality—but, for this record, his songwriting had a holistic intention; an end-goal for a listener’s sustained experience.

Art saw it differently. In a 1973 interview with the Rolling Stone, regarding the lyrical themes of disillusionment and alienation, he said “I never thought they were [important]. I thought the lyric content was an amusing juxtaposition, which is a little strange at best. I was amused that critics should add all those overtones to it. I wonder what they thought, that they should add all those overtones to it. I wondered what they thought was really meaningful about it. Did they think we were really changing anybody? I don’t think so.”

Paul drew the line, in a later interview with the same publication, while remembering his first forays with the topic. He said he wrote “The Sound of Silence” “two years before it came out as a hit single. So, it’s written about a feeling I had then. And it took me a couple of months then to write it. So, a lot of these songs are written in the past, and they come out as if this is what we’re up to. Then, a kid comes back from England with a big hit record, and everybody says, ‘You seem to write a lot about alienation.’ ‘Right,’ I said. ‘Right, I do.’ ‘Alienation seems to be your big theme.’ ‘That’s my theme,’ I said. And I proceeded to write more about alienation… They put a tag on the alienation. And it was a self-fulfilling prophecy, so I wrote alienation songs. Of course we all had a feeling of alienation. [Like all] protest songs were saying, ‘I’m not part of you.’ If the world was full of ‘me,’ the answer wouldn’t be blowin’ in the wind, you know?”

It took most of 1967 for Paul to develop the twelve songs that compose “Bookends,” with half having been offered for consideration in “The Graduate.” Columbia released five singles from the record, with three out before the album (“A Hazy Shade of Winter,” “At the Zoo,” and “Fakin’ It”) followed by “Mrs. Robinson” and, after a long four years, “America.”

“America” was inspired by Paul's 1964 jaunt across the country with his then-girlfriend Kathy Chitty, after he was called home from England to finish mixing “Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M.” The young couplet was hitchhiking state-to-state, looking for what the nation represented as much as they were looking for its scenery. The song “America,” as the biographer Marc Eliot wrote, “creates a cinematic vista that tells of the singer's search for a literal and physical America that seems to have disappeared, along with the country's beauty and ideals.”

The protagonist of the song—one half of “an apparently-impromptu romantic traveling alliance”—has set out from Saginaw, Michigan, to “seek his fortunes elsewhere.” He meets his better half (Kathy; a clear reference to his former muse) in Pittsburgh, and they continue together by bus. With astounding brevity, Paul illustrates the journey they share and the undiagnosed angst—anxiety, anger, emptiness—that permeates them and the country alike. Of the last verse, “counting the cars on the New Jersey Turnpike,” Peter Fornatale believes it to be a “metaphor to remind us all of the lost souls wandering the highways and byways of mid-Sixties America, struggling to navigate the rapids of despair and hope; optimism and disillusionment.”

A few shadowy residents of Saginaw (the supposed hometown of the song's protagonist) have found solace in Paul Simon's lyrics. Once a great factory town, most of the jobs and population have long since absconded from Saginaw, leaving much of the area derelict and dry. “America” has made them feel ‘homesick’ for what the town once was—full of life and promise—and this loose collection of Michigan artists have taken to spray-painting the barren bridges and vacant factories with the entirety of the song's lyrics. The line “All gone to look for America” decorates much of the area's shodden infrastructure — a refrain of nostalgia and despair in the town of Saginaw.

A Rolling Stone readers poll ranked “America” as the fourth best S&G song, and it's widely regarded as one of Paul's greatest lyrical works (including those of his solo discography). Stephen Holder of the Rolling Stone wrote, in 1972, “‘America’…was Simon's next major step forward. It is three and a half minutes of sheer brilliance, whose unforced narrative, alternating precise detail with sweeping observation evokes the panorama of restless, paved America and simultaneously illuminates a drama of shared loneliness on a bus trip with cosmic implications.” The American Songwriter called it “essentially a road-trip song, but like all road trips, it tends to reveal as much about the participants as it does about the lands being traversed.”

These may be the ‘overtones’ Art decries but others have said that this song had “captured America's sense of restlessness and confusion during the year that saw the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, as well as the escalation of the war in Vietnam,” and that it is “perhaps the most representative of Simon & Garfunkel’s music: wistful and optimistic, personal and universal, and—most of all—uniquely American.”

The same could be said for the album itself. “Bookends,” wrote Peter Fornatale, represents “a once-in-a-career convergence of musical, personal, and societal forces that placed Simon & Garfunkel squarely at the center of the cultural zeitgeist of the Sixties.” In the song “A Hazy Shade of Winter,” the line “Time, time, time, see what’s become of me” spoke to those disillusioned youth, knee-deep in angst, as it “defined the moment for a generation on the edge of adulthood.”

Paul had penned the nearly-autobiographical piece in England, 1965, writing of a “hopeless poet” wandering aimlessly towards the future. Specifically, it's late autumn, as the chorus asserts by rote: “I look around, / leaves are brown, / and the sky / is a hazy shade of winter,” and further, “Look around, / leaves are brown, / there's a patch of snow on the ground.” Peter Fornatale has compared the illustrative and evocative lyrics to “California Dreamin’” by John & Michelle Phillips of The Mamas & The Papas.

In a 1984 interview, Paul stated that “Bookends” was his “first serious piece of work.” The breakthrough album clocks-in at just over twenty-nine minutes, with an average of 145 seconds per song. The curt punctuation of each track is evidence of the braintrust's perfectionism in production. For instance, the two-minute-long parodic track “Punky's Dilemma” took over fifty hours in-studio to record, with vocals deliberately re-recorded, note-by-note, at Art's insistence. He wanted absolute precision, and such determination was admired by everyone—save for Paul Simon.

“When you come to ‘Bookends,’” Paul said in his later Rolling Stone interview, “you’re making full use of the studio… That album had the most use of the studio, I’d say, of all the Simon & Garfunkel records.” He has since rated it “right below [their final album]. I rate each album as better than the last one. That’s how I see it. In ‘Bookends,’ we started taking much more time with the singing.”

Art Garfunkel bore witness to Paul's protection (or, domination) of his material and Art stood to ensure a finely-tuned, meticulously-mixed recording of every strum, stroke, and tune. It would be his input; his insistence on having an opinion heard; his word and Roy's against Paul. His perfect ear and pitchpipe voice could detect the slips and lulls of every line.

“Sometimes [re-recording lines] turns into a compulsive thing,” Paul said, and “to a degree that would happen to Simon & Garfunkel. They’d get too perfect which could be disturbing; a part of Roy and Artie’s thing more than mine. Because I always liked more sloppiness than they did. They got to the point where it had to be just right. Sometimes, it worked. Like, ‘Mrs. Robinson’ was punched in a lot, and it worked really good. ‘Bookends’ was recorded sort of half-and-half. ‘Bookends’ is really the one side,” with the other comprised of “the most recent singles — [with] the exception of ‘Mrs. Robinson,’ which was recorded at the same time as the songs on the ‘Bookends’ side. Those other songs were, for me, the dry patch of Simon & Garfunkel…”

As the recording process drew on, their harmonies faded in the mixing, gradually shifting towards solo performances — with assignments and arrangements chiefly decided by Paul. He frequently gave Art the lead, but Art still took issue as it was rarely a team decision. Paul saw it differently, in that each song was born within him as a unique vision to be honored.

“To analyze singing,” Art began, in a 2012 interview with The Guardian, “and to think of what it is like is the devil's business. How you move from one word to another, how you connect the heart to the lyric, and how you chase after the loveliness of a melodic line. It eludes analysis, largely. But to be out on stage and take a breath and hope a perfect sound will emerge, that is always an act of faith.”

Months preceded the production of “Bookends,” but Paul only occasionally conceded influence. In fact, Roy Halee seemed to have had more valuable input than Art regarding the 'final sound’ of the album—and yet, that's not how he remembers it. In 2015, when asked by The Guardian if the songsters of the Seventies owed their style to Simon & Garfunkel's discography, Art said “You could say those artists are children of my sound, yeah. We were folkies; softer, more thoughtful. We work with goosebumps; with melody.” In the era of their partnership, he felt very much “at the center of things,” adding, “There were a lot of moments where I pinched myself with my good fortune. I was certainly aware that we were heroes in this age.”

In “Old Friends,” Paul writes semi-autobiographically, imagining himself with Art in the distant future. “Old friends / Sat on their park bench like bookends.” The space between them, though physically small, is an emotional gulf. As the years have dragged on, their childhood friendship was crumbling as the vines of contempt slithered into cracks formed by ancient betrayals.

Their relationship at this point, though not acknowledged, is purely one of necessity. The adage “don't go into business with your friends” applies even in the music industry. The trials and triumphs of recording have turned Art and Paul against each other. Now they will never be “Old friends / Winter companions / The old men / Lost in their overcoats / Waiting for the sunset.”

The needling of big personality against bigger personality has riddled their relationship with holes. The mere concept of their partnership continuing into the next stages of adulthood is unfathomable. “Can you imagine us / Years from today / Sharing a park bench quietly? / How terribly strange / To be seventy.”

Despite it all, Paul is aware that—regardless of what the future holds—he and Art will forever share an unbreakable bond: victims and heroes of the same storied journey; eternally one half of a harmony — and one so finely practiced that it can be renewed like childhood memories; as seamlessly as mounting a bicycle, as if no time has passed since parting. And of the years to come after, Paul alludes again to the men as bookends of their storied gulf: “Old friends / Memory brushes the same years / Silently sharing the same fears.”

Their relationship suffered under its own weight, and the pressures of Columbia only stood to worsen them. Clive Davis raised the price of the “Bookends” vinyl a dollar above retail, to $5.79, which would be $42.11 if released at the time of this article. He justified the increase by shipping a large poster of the duo inside the record sleeve.

Paul wasn't buying it, and he didn't think anyone else should; he knew hiking the price up by 20% was a greedy ploy to cash-in on “what was sure to be that year's best-selling Columbia album.” Clive took offense to Paul's assertion—presumably for seeing through the corporate rouse—and he denounced Paul's anger as a “lack of gratitude for what he believed was his role in turning them into superstars.” Paul negotiated to get the price back to retail value, and it cost him a two-year contract extension with Columbia, to 1970.

“Bookends” received such a magnitude of preorders that they were RIAA certified even before the vinyls were printed. It was instantly a bestseller, raising the duo to the highest echelon of music artistry, alongside acts such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan. As leaders of the airwaves during a cultural revolution, their influence was immeasurable. The impact of “Bookends” on the American youth was so great that even the album cover has gone on to inspire homages.

Following the back-to-back successes of “The Graduate” soundtrack and “Bookends,” Paul Simon was inundated with requests from Hollywood producers and directors to write original soundtracks or license the duo's recent hit tracks. He turned them all down, citing the overtly-commercial milking of pop culture as ‘disgusting.’

“Bookends” was not a gold mine for capitalists, it was an artistic masterpiece—what The A.V. Club called the “most musically and conceptually daring album” of their discography. Reviewer Stephen Deusner said “Bookends” was the album wherein Art and Paul “were settling into themselves, losing their folk revival pretensions, and emphasizing quirky production techniques to match their soaring vocals.”

Others weren't so kind. Arthur Schmidt of The Rolling Stone wrote of “Bookends,” “The music is—for me—questionable, but I've always found their music questionable. It is nice enough, and I admit to liking it, but it exudes a sense of ‘process,’ and it is slick, and nothing too much happens.”

“They’d get too perfect,” Paul recalled. He was deflated by such reviews, as he had stood by as Roy and Art re-recorded his lines, surgically, note-by-note; eschewing authenticity and mixing with meticulous precision; “a compulsive thing…”

While Art enjoyed “touring; sex-for-thrills on the road,” Paul was still bitterly unhappy. Between them, there was little conversation; “silence like a cancer grows.” Alone, Paul fell victim to his dark thoughts of inferiority and adequacy. He came to believe he could only write when his true mind was quieted; when those higher powers who gave him the gift of the bard could speak freely.

He turned regularly to the packed bowl (re: cannabis) though he knew it took an emotional and spiritual toll on him. It fed his darkness despite freeing him of his self-loathing long enough to put pen to paper. It caused him to “retreat more into myself,” seeking subconsciously a hideaway on tours, to drown in smoke “the pain that comes out in some of the songs” which was often exacerbated by “being high.”

“During some hashish reverie I was thinking to myself, ‘I’m really in a weird position. I earn my living by writing songs and singing songs. It’s only today that this could happen. If I were born a hundred years ago I wouldn’t even be in this country. I’d probably be in Vienna or wherever my ancestors came from—Hungary—and I wouldn’t be a guitarist-songwriter. There were none. So what would I be?’ ‘First of all,’ I said, ‘I surely was a sailor.’ Then I said, ‘Nah, I wouldn’t have been a sailor. Well, what would a Jewish guy be? A tailor.’ That’s what it was. I would have been a tailor. And then I started to see myself as like, a perfect little tailor. Then, once talking to my father about my grandfather, whom I never knew—he died when my father was young—I found out that his name was Paul Simon, and I found out that he was a tailor in Vienna. It wiped me out that that happened. It’s amazing, isn’t it? He was a tailor that came from Vienna.”

These were heavy hashish times for Paul Simon. “This was 1967, you know. The summer of flowers.” His partaking began in England, when hashish (a paste made of cannabis resin) was introduced to him by his fellow folk singers. In the Sixties, “dope…meant you smoke grass or you smoke hash. In England everybody smoked hash; nobody smoked grass. Or you maybe took some pills; took some ups or downs.”

And sometimes he did. Not often, but, “Yeah, I took pills,” and it only made his outlook worse. “A negative effect at that point… It made me retreat more into myself. It brought out fears that I had, and I don’t think it helped me in my writing, although I was convinced I couldn’t write without it. I had to be high to write. It didn’t matter, because I was high every day anyway. But I think a lot of the pain that comes out in some of the songs is due to the exaggeration of being high. When you start to get into a depressed thing when you’re high, it really tightens you up then. You get really wound up in it. And I was by myself a lot. I was touring and then I’d be by myself.”

Art wasn't around much. “We saw each other so much on the road,” Paul said, “by the time we got back, there was no need. We were pretty good friends then, but we saw each other several days a week…so we didn’t see each other when we weren’t.”

Contrary to Paul's experiences, Art went up with his back-alley medication. It fueled his growing confidence and ego. He tried grass, hash, and LSD. “They were great fun. No bum trips,” he said. And, before you ask, “No,” he “never took acid with Paul.”

“I tried acid a few times, and I didn’t like it,” Paul said. “I had a very whopping acid trip once. Owsley gave me some acid, and I took it by myself, in typical fashion, late at night. I said, ‘Well, I’ll try this now.’ About three in the morning, I dropped it, and I continued right on through until about nine the next night. It was some good and a lot of bad. I had a stretch of about four or five hours that was very paranoid… I remember during the bad part thinking that it was vanity that made me take it. I took it because I thought I was going to get some big chunk of information for free. I was going to learn something about myself chemically, rather than learning something through my life. I said, ‘Look what I’ve done. I’ve fucked my brains up here.’ I thought I’d get this tremendous insight, that glint, that San Francisco…something. I’d see something. I’d know something. At the depth of the thing, I said, ‘Here it is, there I am, there’s me. The same guy I knew before I started. Got the same things I like. Got the same things I don’t like. It’s the same guy, except at this moment I’m really afraid, and I’m afraid because I’ve got a chemical in my head.’ But that didn’t stop my heart from pounding and being afraid.” And yet, “after that, I went right back and did it again — sort of the ‘falling off a horse’ theory. I wasn’t going to let any acid trip throw me just because it was bad.”

“I would say it was stupid behavior on my part… Just stupid. I did it because a lot of people were doing it, and I was curious to know what would happen. I hallucinated. The funny thing was during the whole time, it was like there were two parts to me. One part was absolutely high, and the other part of me was saying, ‘That’s high, and if you get really high, you can think that, if you take acid, you can look at your hand and think that it’s curling back at you or anything you want, or you can listen to music and think it’s the most heartrending thing you ever heard.’ But another part of me is saying, ‘Wait a minute, I know that music, I remember that music from before. It wasn’t that great.’ So I never allowed myself to be one person. It made me a little schizophrenic, I guess… And I didn’t get anything from it. I didn’t get anything from it… I think it was like taking a beating. I think I came out of it about six months later. Somewhere around six months later, I said, ‘Oh, I think I feel about normal now.’ I wasn’t aware of it, but I think that’s what it was like. It was exhausting for nothing. For vanity, that’s what. That I thought I was going to learn something, that I didn’t learn.”

“So…I stopped a couple of years ago… Nothing. Zero. I don’t smoke. I don’t pill. I don’t anything… It was very unsatisfying for me at the end, although I started out loving it. But at the end, it was bad. I couldn’t write. It made me depressed. It made me anti-social. It brought out nastiness in me. When I’d deal with people while I was high, I’d listen to them, and think, ‘Boy, he’s really stupid. That guy’s really phony. Phony smile, phony everything.’ And I couldn’t stand it. I didn’t want to be around.” He went out and found help from a psychiatrist. “...and the day I started analysis, I stopped… The doctor said, ‘I can’t analyze you if you are high.’ I think he said that because he knew I wanted to stop…and I took that as a good enough reason… And a year later I stopped smoking cigarettes, too… Because when you smoke, you can’t sing good. When you were high, you couldn’t sing good; your throat got tight. It was a big improvement in my voice. My range went up; my ability to sing and phrase—everything got better.”

Art’s affinity to smoke cigarettes, on the contrary, worsened within his social bubbles of the rich and famous. The smog of Marlboro was thickening his throat and his vocal register was dropping, slowly but surely. His friends kept him supplied with grass and acid. He went on vast trips inside his living room, bearing witness to “funny shadowy things; clouds passing, making that warmth of shadow and light—happening things; extra presence of living things—plant life. A lot of that ‘Alan Watts feeling’ about existence: ‘This is it; this moment is what it always does feel like, so there’s nothing more than this feeling of what it feels like to be alive…’”

“For me, acid was a very humbling experience, but the drive to succeed in show business is achievement-oriented; [acid is] anti-humility in a way. If you’re humble and you can sing, why not sing for friends you can look at and give them pleasure? On a one-to-one basis?” “Unless,” the interviewer suggested, “you’re the type who wants to humble yourself in public.”

Art replied with a shrug. “But I suspect some kind of ego strives in there.” He paused. “I can identify with a certain appreciation, but here I have to get very personal, spiritually. My concept of God showed up as if to say, ‘It’s lucky that you’re able to sing; it’s a sweet gift to be given, and the response to it should be some kind of responsibility.’ That’s what inspires me to see myself as a potential pleasure-giver. That’s what got me back into making this album. The insights I got had a lot to do with seeing the real from the not-real, and the real pushed me on to concentrate on what I can do and try to see noise for noise’s sake. Because what you can do, you should do. What else are you supposed to do with your time on earth?”

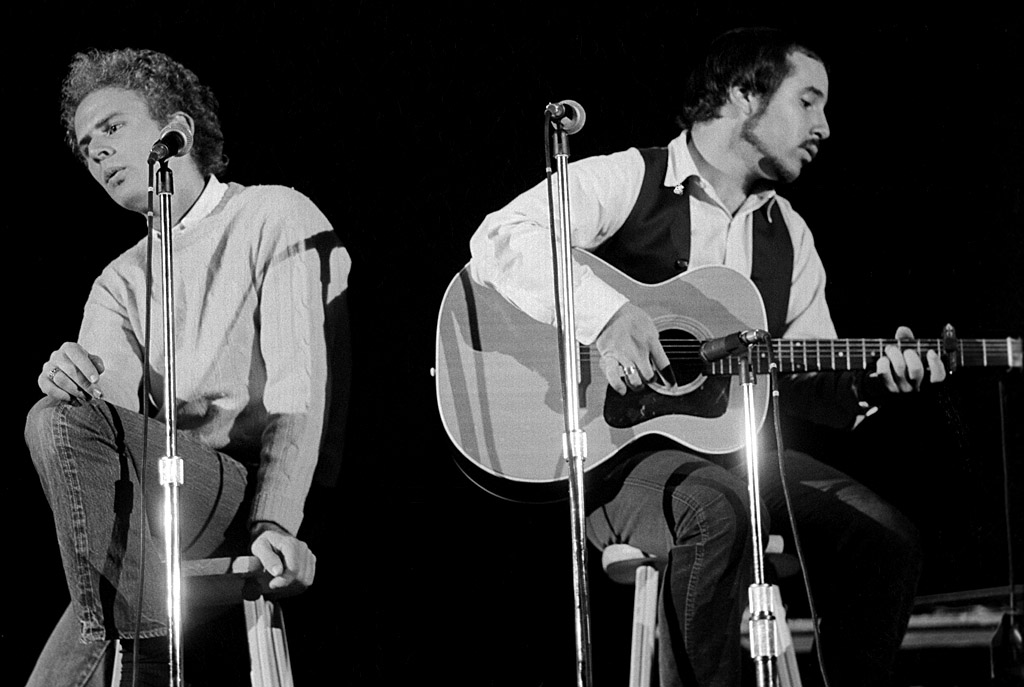

Simon & Garfunkel toured England in autumn of 1968. They performed earlier that year on the Kraft Music Hall, broadcast throughout America and the BBC. Standing atop a table-sized stage, surrounded black box-style by an intimate and pillared audience, the duo began with “A Poem on an Underground Wall.” Paul played the guitar as if he were alone in his parents’ bathroom. Art smelled the air before soloing “For Emily, Whenever I May Find Her,” and he bathed in the subsequent applause.

1968 was the duo's most active year for concert touring. Whilst traveling, Paul worked on writing the album he had promised to deliver by 1970. Art spent his time reading—philosophy, poetry, and philatelic literature—or socialising; blossoming into a night owl and conversationalist. Paul kept to himself, largely owed to his depression and anxiety, made worse by hash.

“On the road, I remember things were pretty pleasant from the point of view of us getting along. It was hard and boring to travel so much,” Paul said. “I always felt weird on the road. I was in a state of semi-hypnosis. I went into a daze, and I did things by rote. You got to the place, you went to the hall, you tested out the microphones, changed your guitar strings, read the telegrams, found out who was coming to the concert that you knew, and planned out what you were going to do after the show, and usually tried to find a decent restaurant in the town—and that was it. Just sort of hung out with friends, assuming that there were friends in a place.”

Paul thought aloud, referring to his partner in saying, “I don’t think the road had much to do in exacerbating our relationship because, first of all, we weren’t on the road that much in the end. The breakup had to do with a natural drifting apart as we got older and the separate lives that were more individual. We weren’t so consumed with recording and performing. We had other activities. I had different people and different interests, and Artie’s interest in film led him to other people. His acting took him away, and that led him into other areas. The only strain was to maintain a partnership. You gotta work at a partnership. You have to work at it… You got to…”

Mike Nichols was making another film: an adaptation of Joseph Heller's satirical anti-war novel, “Catch-22.” Nichols and Buck Henry, the screenwriter of “The Graduate,” teamed-up after the 1967 film wrapped to write the black comedy, taking two years to get something worthy of Heller's approval. The film (to be released in 1970) featured Alan Arkin, Bob Newhart, Jon Voight, and Martin Sheen, with secondary roles written for Art Garfunkel and Paul Simon.

The film depicts Captain John Yossarian, a U.S. Army Air Force B-25 bomber pilot, who tries to get discharged after losing a dozen friends in an air raid. His commander has increased the number of missions required to go back to the States, from 25 to 80, and surviving to accomplish eighty missions is essentially impossible. As the airbase doctor explains—thereby immortalizing a common logic term—anyone willing to attempt eighty missions invokes Regulation 22, whose contradictory nature is now nearly as popular as George Orwell's ‘doublethink.’

The dilemma appropriately called “Catch-22” implies that a pilot would be certifiably insane if he committed to eighty missions, and if he were insane he should not fly. However if he refused to fly, it's because he is sane, which means he is fit to fly, so he will fly—but if he obeys orders, he would be crazy, so he is unfit to fly, and so on, and so on. Damned if you do, damned if you don't.

Paul was set to play the role of Dunbar, a pilot trying as desperately as Alan Arkin's Yossarian to get a discharge. Artie was cast as Captain Nately, a pilot who falls for an Italian prostitute. Mike Nichols had wanted both boys from the S&G double-act to be included in this production, but screenwriter Buck Henry felt the script was overly crowded with the novel's many characters. He cut Paul's role, kept his own (that's right, he wrote himself a role), and he boosted Arthur Garfunkel to fourth-billing.

“That was the beginning of their split-up,” said documentarian Charles Grodin. “You don't take Simon & Garfunkel and ask them to be in a movie and then drop one of their roles.”

Art committed himself to the role of Captain Nately, which Paul perceived as a knife in the back. He'd been gypped; he'd been insulted; he'd been betrayed. Captain Nately was Paul's True Taylor for Artie Garr.

Production of “Catch-22” went on for longer than expected, adding to the bitterness. Art didn't think it was a big deal; roles get cut and shoots run long. “Rather than wait for Paul to write the next bunch of songs, I went off and did this movie.”

“Our way of working was for Paul to write while we recorded. So we'd be in the studio for the better part of two months working on the three or four songs that Paul had written, recording them, and—when they were done—we'd knock off for a couple of months while Paul was working on the next group of three or four songs. Then we'd book time and be in the studio again for three or four months, recording those.”

Working among the Hollywood crowd, Art was welcomed into their debauched underworld of ladies, ladles, and laudanum. “I discovered Hollywood. I lived in LA, in Malibu—I was with Laurie then—I made a film with Jack [Nicholson]. I liked the acting community. We hung out. I went to dinner, and some film director would recognise you and say, ‘Come to the house,’ and you’d go and smoke a joint. You’d trade scraps of paper with phone numbers on. That was the time of staying up well after midnight.”

The filming of “Catch-22” lasted eight months. Paul was stuck waiting on Art to be available before he could move forward on their album, and Roy Halee was stuck in limbo alongside Paul. Art had promised to return directly to the studio as soon as production wrapped, but that day kept being pushed out further and further. Paul had grown beyond frustrated—he was irate. (And Roy was frustrated, too.)

Simon & Garfunkel were invited to perform at the Woodstock Festival in August of 1969 but, unfortunately, that was the last month of shooting for “Catch-22.” Art wouldn’t be available until September, and so Paul Simon missed-out on being a headlining act for what was the most pivotal moment in modern music history, as well as “the definitive nexus for the larger counterculture generation.”

In 2004, Rolling Stone listed the Woodstock Festival as one of the 50 Moments That Changed the History of Rock’n’Roll. “On the weekend of August 15, 1969, an estimated 400,000 people from all over America descended on the 600-acre dairy farm of Max Yasgur, in Bethel, New York, for a three-day concert, the Woodstock Music and Art Fair. On Monday, August 18, they all melted back into America after witnessing legendary performances by, among others, the Who, Santana, Janis Joplin, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Joe Cocker, Sly and the Family Stone, Jimi Hendrix, and—in only their second live show together—Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.” It was a weekend of peace, love, community, “mud, nudity, and rock’n’roll.” Joni Mitchell, the Canadian version of Paul Simon, said that “Woodstock was a spark of beauty” where nearly half-a-million kids “saw that they were part of a greater organism.”

And, while the cultural spectrum was changing colors in upper New York state, Paul Simon was stewing in a dark room in Los Angeles, waiting for his partner and thinking about how good their relationship once was. Blanketed in emotion, a song began to take shape in his head. It had gospel and orchestral bones, and an almost holy aura to it. It was born of loyalty and compassion, and the texture of the voices was somber, as if sung from a deep and full heart, aching with devotion.

“We were in California,” Paul told the Rolling Stone. “We were all renting this house. Me and Artie and Peggy were living in this house with a bunch of other people throughout the summer. It was a house on Bluejay Way—the one George Harrison wrote ‘Bluejay Way’ about. We had this Sony machine and Artie had the piano, and I’d finished working on a song, and we went into the studio. I had it written on guitar…and I said, ‘Here’s a song, it’s in G, but I want it in E flat. I want it to have a gospel piano.’ So, first we had to transpose the chords and there was an arranger who used to do some work with me, Jimmie Haskell, who, as a favor, he said, ‘I’ll write the chords; you call off the chord in G and I’ll write it in E flat.’ And he did that. That was the extent of what he did. He later won a Grammy for that.”

“Now, the song was originally two verses, and in the studio, as [session pianist Larry Knechtel] was playing it, we decided—I believe it was Artie’s idea, I can’t remember, but I think it was Artie’s idea—to add another verse, because Larry was sort of elongating the piano part, so I said, ‘Play the piano part for a third verse again, even though I don’t have it, and I’ll write it,’ which I eventually did after the fact. I always felt that you could clearly see that it was written afterwards. It just doesn’t sound like the first two verses.”

“…it took us about four days to get the piano part [and] then the piano part was finished. Then we added bass… Then we added vibes in the second verse just to make the thing ring a bit. Then we put the drum on, and we recorded the drum in an echo chamber, and we did it with a tape-reverb that made the drum part sound different from what it actually was, because of that afterbeat effect. Then we gave it out to have a string part written. I gave the song to—I can’t remember now who it is. But the arrangers wrote the title down as ‘Like a Pitcher of Water.’”

“I had it framed. The whole string part—instead of having ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ on it—the way the guy heard it on this demo tape was ‘Like a Pitcher of Water.’ So that’s what’s written down. And he spelled ‘Garfunkel’ wrong. So we did the string part, and I couldn’t stand it. I thought they were terrible. I was very disappointed. It had to be completely rewritten. This was all in L.A. And then we came back to New York and did the vocals. Artie spent several days on the vocals.”

The vocals were inspired by The Righteous Brothers in “Old Man River” (mixed by future-murderer Phil Spector) and gospel music, which Paul was listening to religiously throughout 1969. The Swan Silvertones song “Mary Don't You Weep” had the line “I'll be your bridge over deep water, if you trust in my name,” further aiding to the vision Paul had for this song, which was morphing from an olive branch for Art into a hymn honoring his then-girlfriend Peggy Harper. The song was finished in two months. Nearly a hundred artists have covered it since.

Decades later, at his final live show, Paul cradled his guitar and leaned into the mic. There was hesitance—regret, even—in his voice as he began, saying “I have a strange relationship to this next song… I wrote it a long time ago and when I finished it I said to myself, ‘Hmm, that’s better than I usually do.’ Then I gave it away, and I didn’t sing it for a long time… Occasionally I’d try it on tours, though I never actually felt like it was mine since the original versions are so unique. But, this being the final tour, I’m going to be playing my lost child.”

Paul had written “Bridge Over Troubled Water” while Art was off playing ‘Hollywood’ on the Paramount studio lot. “He’d come back and I’d say, ‘Here’s a song I just wrote, ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water.’ I think you should sing it,’” he told the Rolling Stone. “I’d say, ‘We’ll do this with a gospel piano and it’s written in your key, so you have the song,’ [but] it was his right in the partnership to say, ‘I don’t want to do that song,’ as he said [because] he didn’t want to do it… He didn’t want to sing it himself. He couldn’t hear it for himself. He felt I should have done it. And many times I think I’m sorry I didn’t do it.”

Art was interviewed by the same journalist a few weeks later. He was asked, “On ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water,’ you originally didn’t want to sing the lead vocal in that song?” to which he replied, “False. Paul showed me ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ and he felt it was his best song. I felt it was something less than his best song, but a great song. I knew that the way he was singing it was terrific; he had a lot of feeling for it; he sang it in a high range and he got into falsetto and I thought it was a very interesting sound for him. And my first instinct was that Paul could do a bitch on that vocal. I knew I could, too.”

Within each of them was a kernel of grief. Inside Paul, resentment was simmering; inside Art, conceit had sprouted into spite. In other musical unions—such as The Beatles and Fleetwood Mac—spite-fueled passion gave life to subtly-cruel yet great, immortal songs. With Simon & Garfunkel, however, Paul did not make such concessions or calculations in his music. Neither lyrics nor arrangement were biased; the success of Simon AND Garfunkel was the success of Paul’s ability, and slighting Art was not only immoral but counterintuitive.

Paul had never intentionally slighted his partner. The True Taylor incident was not meant to be machiavellian; it was an ambitious kid searching for a foothold at the base of an edifice; it was a misstep and a mistake. Despite what Art came to believe, Paul still cared deeply for his old friend. He loved Art regardless of the hours spent ignored, the events gone uninvited, the concerts missed, the sessions postponed, and the constant bickering about arrangements.

Art had systematically constructed “Bookends” by outvoting Paul with the sound engineer, Roy Halee. The authenticity of his lyrics and crisp guitar—and harmonies, once sung on a shared mic, now separate—had been denigrated with plastic surgery; with Frankensteinian tweaking and over-correction. As a reviewer noted, Art’s method “exudes a sense of ‘process.’”

It cannot be expressed enough that, despite all of the spite and nitpicking and attitude that Art threw at Paul and his songs, Paul always did what was best for his partnership and their album. So, when he wrote “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” he envisioned his partner’s falsetto ringing through cathedral halls, resonating and transcending to the heavens; the voice of an angel singing like prayer on a through-line to God himself. And Art said, “No—you do it.”

And how did Paul react? According to Art, “wrongly. I think he picked up mostly on the fact that he thought it was his best song, and I didn’t give him full credit. I think that right after I said, ‘Ah… I think you could do a great job on that song.’ He said, ‘No, you should do it. I wrote it so that you would do it,’ and I said, ‘Crazy. I’ll do it.’”

“I knew Paul wrote a gem, so I wanted to deliver the potential of that wonderful song. That was a special case. The final verse has the dramatic peak, and it was news to me that I could open up and be that big and high and powerful. That was a transcendent experience. The second verse was easy: build-up to the power. The superfine delicacy of the first verse was maddeningly elusive. Pitch has to be perfect; the feel and emotionality has to be there; the context has to fit; diction and articulation can’t be too clean otherwise it’s too ‘music student.’ I’m a perfectionist. If you’re 99% toward a vision—to me—the Gods live in that last one percent. It may look like a madman’s concern to gild a lily but human beings have incredibly fine invisible antennae, and when things are tooled with infinite precision we pick that stuff up.”

Whereas an admirer of authentic music—folk, punk, rap—might prefer the raw, unpolished sound, Art was transfixed with mixing. It went back to his youth in his basement, with the wire recorders, playing his voice back to himself and singing it again with the slightest of inaccuracies corrected. Were he a painter, his obsessive strokes would bury the canvas an inch deep in oiled pigment. In recording “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” Art sang the first verse over three-hundred times until he got it to sound what he deemed “perfect.”

“When I did the vocal I did the big last verse first and nailed it. But the first verse required a delicacy that was maddening. I couldn't get it.” He went to Saint Bartholomew’s church in Manhattan—an ornate Episcopal parish founded in 1835 and rebuilt in 1903 of the Romanesque and Byzantine Revival styles—and, kneeling in the pews, he prayed. “It was just: ‘Lord help me relax. Help me find that lovely place as a performer when you believe you get a visitation from higher powers, and it passes through you.’”

He asked God for the ability to surpass his own hurdle; his self-imposed challenge of the verse. Paul had written “Bridge Over Troubled Water” as a short hymn; a religious promise. When he introduced the piece to Art, after “Catch-22” wrapped, Art heard it “as this two-verse beautiful hymn of peace. But I thought it had the possibility to go into high gear—do this Phil Spector thing—and take off.” It was a tonal shift that Art not so much requested as demanded. He agreed to take the lead on “Bridge Over Troubled Water” only if Paul wrote a third verse that allowed him to flex his vocal cords and “really make them cry in the aisles,” as he had done in the synagogue, so many years ago.

At first, Paul objected. “He is like a purist, in that way. ‘No, Artie, I wrote it as a hymn.’ But he did open himself up to it and wrote the third verse…” “You can look at songwriting—at which Paul Simon is clearly a master— and you can look at singing—the Frank Sinatra part of the thing, which we both did. In between the two is record making.”

“We were inspired by a Phil Spector production of the Righteous Brothers singing ‘Old Man River,’ many years ago on a forgotten album, on which they sang with spare production throughout until the very last line of the song… ‘Tired of living and feared of dying / but Old Man River…’ and on that line, they threw in everything. The studio sound quadrupled in size and the Spector girls’ chorus entered, and they vamped-out with a very hard-driving fade, repeating ‘Old Man River…’ and then just wailed on out. Well, that killed me. Saving the production for the last line of a song seemed like all of that potential energy running through the whole record until it exploded. It was a lovely production idea. When we did ‘Bridge,’ it was a two-verse song, and once I got into the vocal I felt it should be personal and simple and sort of unproduced. But we said, ‘Let’s use that Spector idea.’ And then we said, ‘Well…we need a third verse, quick,’ and it was really just that kind of thing. We began to hear the record you could make and all that was missing was some more song, and because we were driven…everything fell into place, in a very natural way. It took Paul just a couple of hours to write the last verse in the studio. That’s when it goes good. It sort of makes itself. That’s what ‘Bridge’ was for us.”

“Many times on a stage,” Paul told the Rolling Stone, “when I’d be sitting off to the side, and Larry Knechtel would be playing the piano and Artie would be singing ‘Bridge,’ people would stomp and cheer when it was over, and I would think, ‘That’s my song, man. Thank you very much. I wrote that song.’” Pausing before what was akin to a repentance at confessional, Paul added, “I must say this: in the earlier days, when things were smoother, I never would have thought that—but towards the end, when things were strained, I did. It’s not a very generous thing to think, but I did think that. I resented it, and I must say that I was aware of the fact that I resented it, and I knew that this wouldn’t have been the case two years earlier.”

In the summer of 1969, at the Bluejay Way house outside Los Angeles, Paul was alone. It was around the same time the Manson Family were slaughtering six innocents at Roman Polanski’s house, a few miles away. Art Garfunkel was off filming “Catch-22,” still, and Paul roamed the house aimlessly. He tinkered with the instruments and objects in various rooms, capturing with a tape recorder the sounds of klinks, clangs, and clatters, such as the falling of drum sticks or the tinkling of a xylophone. He picked up his acoustic guitar and fell to the floor, to his knees. He looked around the barren room and through the sliding glass door, at the Sunset Strip below. The Hollywood Hills flanked him on the left, and the Holmby Hills flanked him on the right. He was alone. A line appeared in his heart, and he sang, “You're breaking my heart. I'm down on my knees,” which subsequently grew into the song “Cecilia.”

Paul had written the majority of another song, “The Boxer,” the year prior. The recording sessions for “The Boxer,” in the spring of 1969, were particularly brutal. Though Art was not often around, given his commitment to Mike Nichols at the beginning of the year, he required over one hundred hours of revision to ‘perfect’ this one song. They even ventured back to Art's alma mater, Columbia University, to record a horn section inside St. Paul's Chapel.