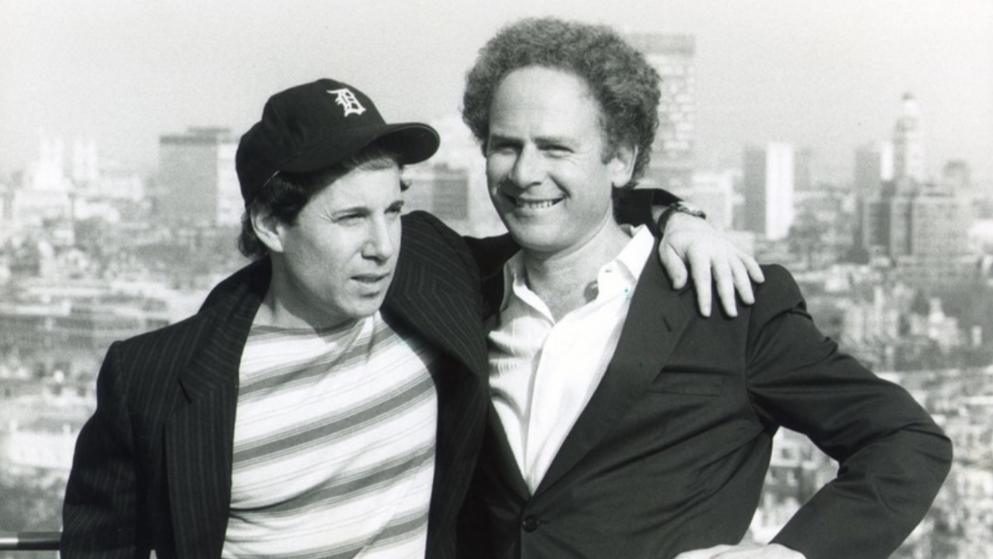

Our tale now comes to a close, as the entwined legacies of two halves taper toward a certain infinity. The year is 1984; the place, Manhattan. Two men—closer than brothers yet further from friends—reside on opposite ends of the urban island’s greenway — a landmark of recent consequence for them both.

Chronos guides each man with gentle hand, up the broad-sloped hill from which they will soon descend, west toward the setting sun and the hereafter. Each personality has been written in stone, and the bedrock of a life’s work has shaped the quality of his impact to come. May his influence bear testament to his character and success for all future generations.

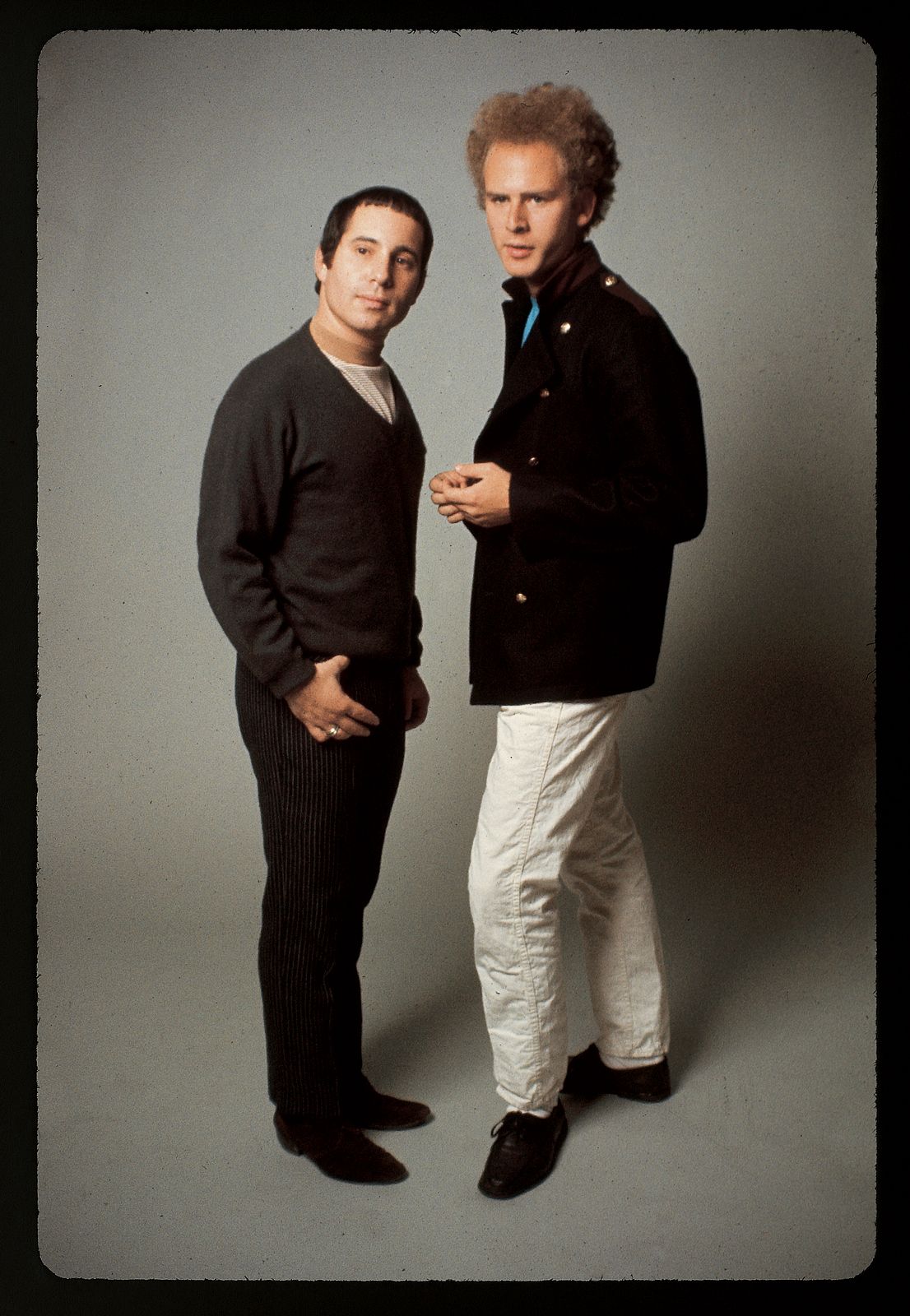

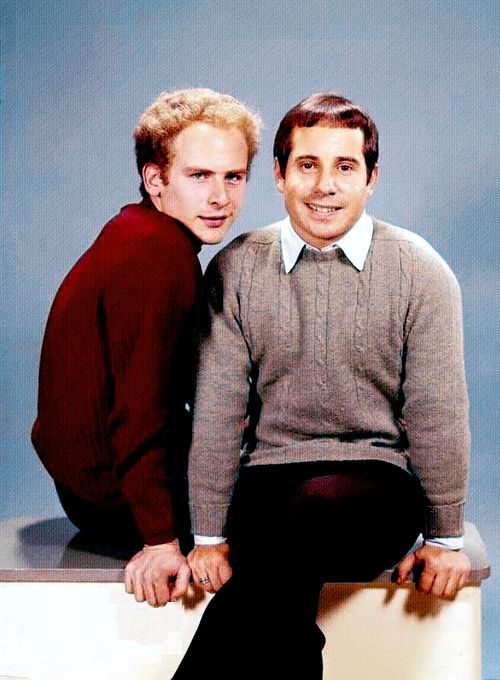

To one, the work-obsessed auteur, life has been a mission; to the other, the self-obsessed performer, life has been a stage. Like any of their albums, they’ve written their histories as much together as independently—though the bulk has been shaped by the bard—one song at a time; one breath at a time; like droplets of hot water steadily filling a cold glass.

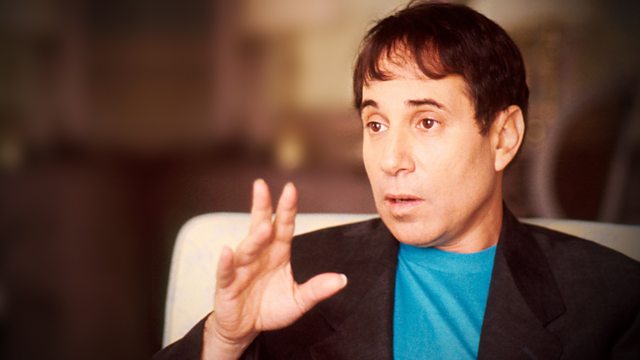

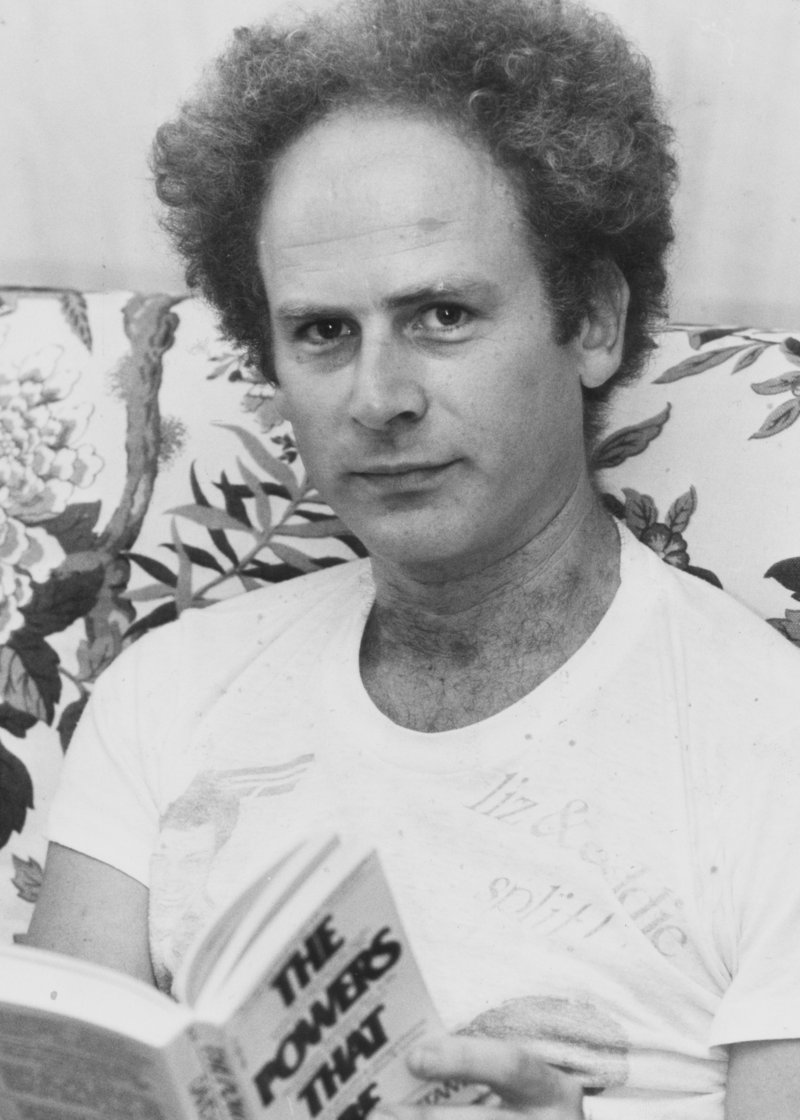

The proud performer had drawn inward, becoming a haughty egoist, and self-pleasured. Always his counterpoint, the conscious auteur had grown outward, expanding his musical sound, enduring emotional turbulence, and achieving greatness, though evermore insecure of it.

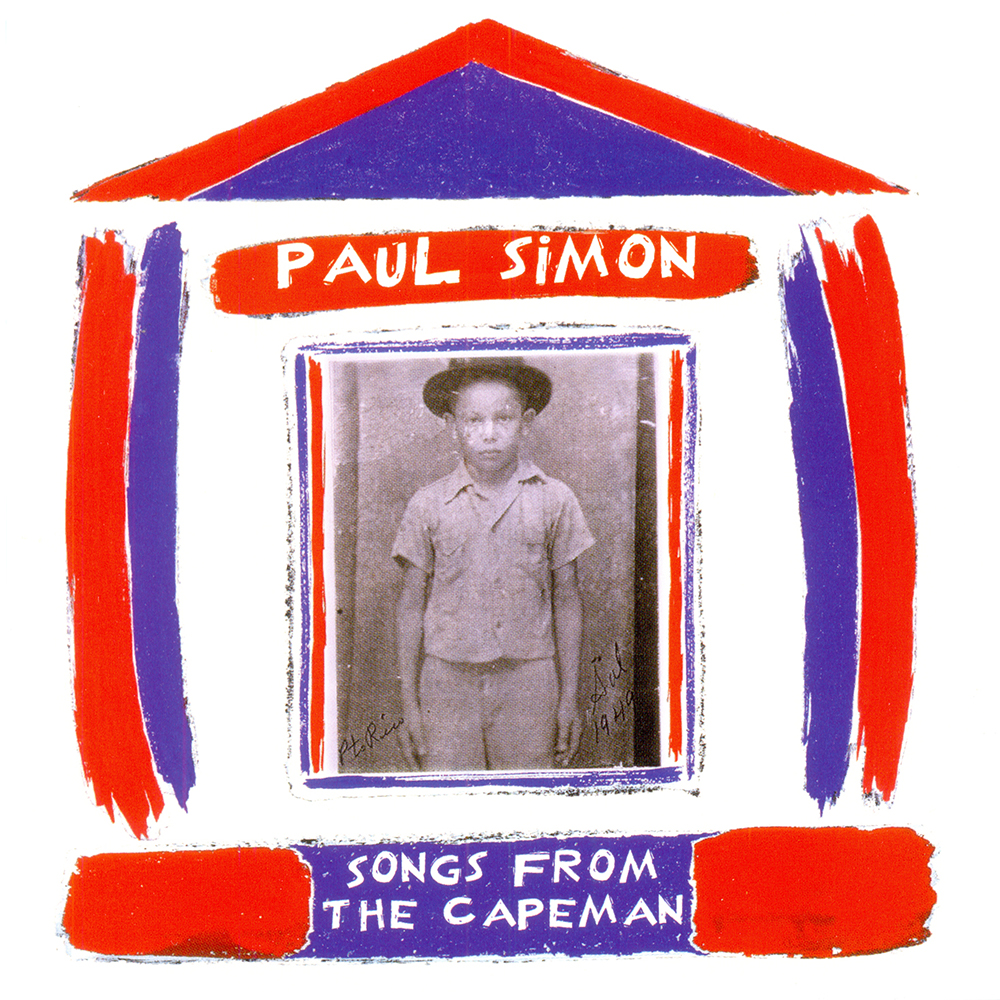

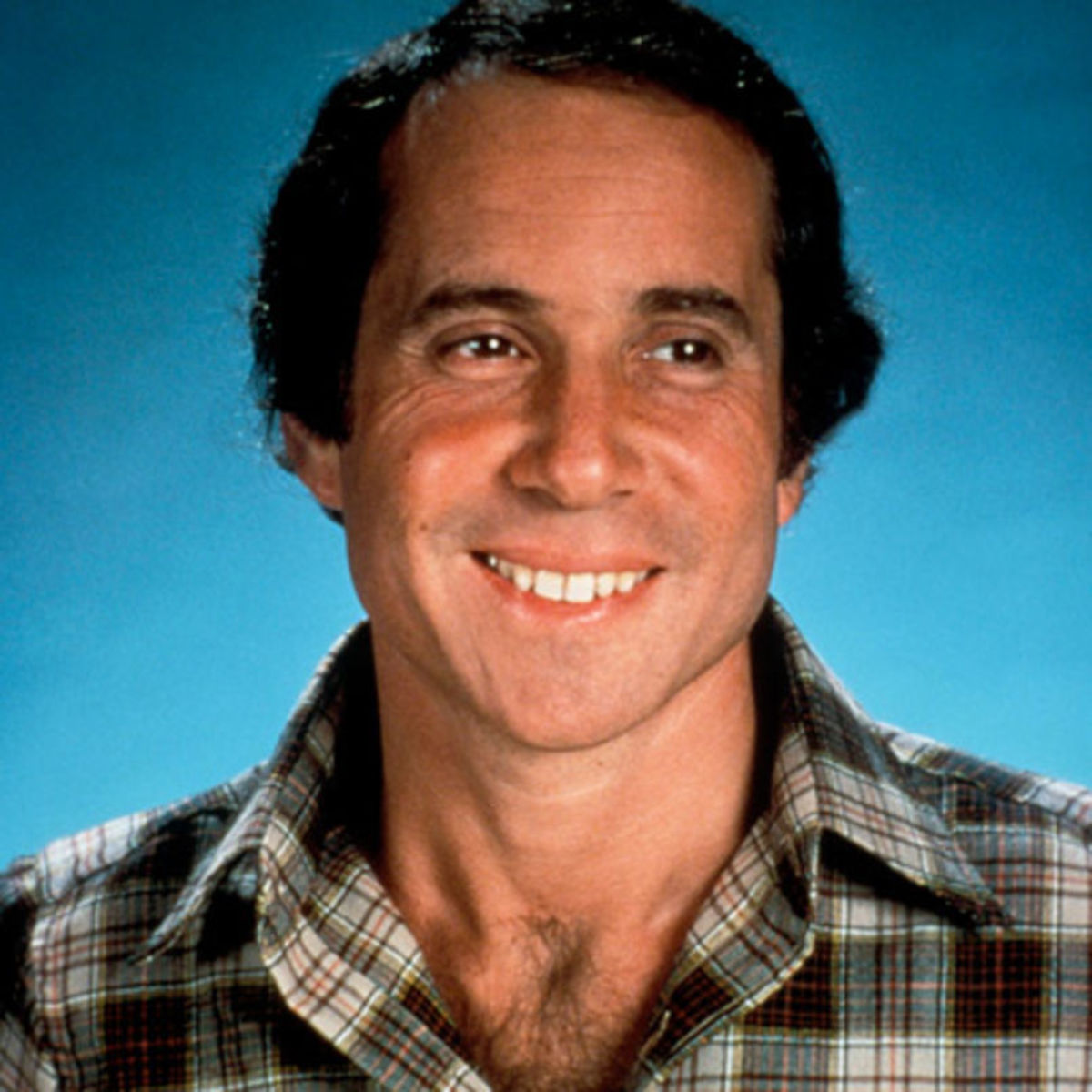

In growth, the auteur exposed himself to the world, and the world fed upon him in exchange for confidence. The performer never feared such exposure; he constructed his own world, where he could always be comfortable and confident; where wisdom, prose, and an angels’ choir sustain his aura of recognition and esteem. And out of the great Paul Simon's shadow, he has carved his own niche, and he is happy to die there.

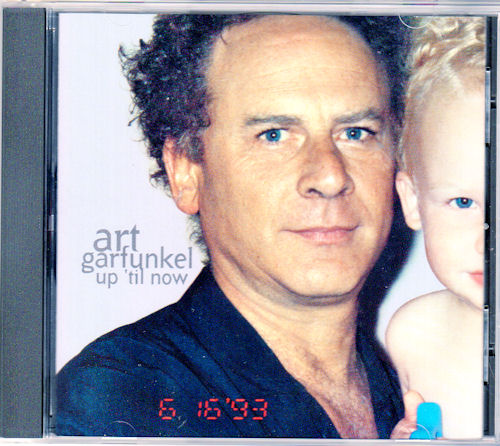

Paul may forever be dissatisfied despite his marble bust standing in the hall of heroes, but Art Garfunkel stands defiant, proudly preferring he be immortalized in a box with his face on it. Any sized vestige of his individuality would be a better tomb than residing in the eternal cultural memory as only one half of Simon…

And Garfunkel:

Life in the Shadow of the Bard

— Chapter V —

Homeward Bound

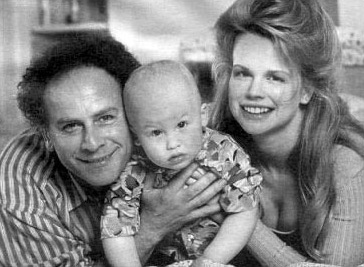

Nobody recognized him in Japan; that was what made it so easy. He stood a head above everyone else, with chalkier skin, a prominent nose, and a bushy crown of dry orange hair, but in the rice paddies and cherry blossom-lined roads of Japan, there were few interruptions. A walk through Tokyo became, with endurance, a walk across a nation; a long-form panorama of a culture.

His interactive history lesson and light-exercise adventure inspired him to replicate his feat at home. It would be the second time in his life [without prompt or push] where he would willingly expose himself to an experience he didn't already know the outcome of. Such exposure would bestow him the inspiration that had always eluded him.

“I became a writer for the first time in my life,” he told The Guardian, “not a songwriter, but a literary guy… I started writing in the 1980s—just these little fragments and pages, which I continue to do. I am also working on the story of my life, sketching who I was; how I came to have this voice that raises goosebumps; how I met Paul Simon. All of that,” in poetry.

In 1984, he released his first compilation album, “The Art Garfunkel Album,” in the UK. (Columbia did not release it in the US.) The album featured his thirteen most popular songs from his solo career—all covers and Jimmy Webb tunes—with a fourteenth track as a single: the yet-unheard “Sometimes When I'm Dreaming.” It peaked at #77.

After the Concert in Central Park, and prior to the subsequent S&G world tour, Art visited Japan on furlough. He ventured an impromptu three-week hike across the Far Eastern island, alone with his thoughts, thereby reawakening his love of spectatorship, introspection, and natural aromas. In 1984, on a whim, he walked out the front door of his Manhattan apartment, cut through Central Park, crossed the George Washington Bridge, and strode into New Jersey—hic sunt dracones; here be dragons—gone to look for America.

“Over forty more excursions—about three a year, taking about twelve years—I crossed the entire United States,” on a route shepherded, scouted, and overseen by an aide. However, Art never paid the boy much attention. “Most of the time I was alone with my Sony Walkman and my notebook in pocket… I take a little journal. I don't look for experiences, I just keep trucking. The physical body takes over. It is the cosmic exhale that I pursue. Eyes and breath.”

His cross-country trek was done in spurts: a few score miles here and there, then a flight back to Manhattan, and—whenever he felt like walking again—a flight back to where he left off. In this unorthodox noncommittal manner, it would take Art fourteen years to walk from New York City to the Pacific shores of Oregon.

In a 2015 interview with The Guardian, Art contended, “I walked across America—before Forrest Gump! He stole it from me! And I walked across Europe! And I always think about skin cancer on the nose!”

No longer the “Carnal Knowledge” fountain of sexual magnetism, his face was a generation-too-late to be recognizable; his skin had wrinkled and sagged; his hair lost its luster. He looked like a normal guy. On his long walk, Art attributed the lack of interruptive photo ops to his bucket hat and goal-visualization.

“I had a goofy hat on to protect against the sun. I go invisible… If you carry a spirit inside that says, ‘I am Mr Nobody,’ you become Mr Nobody. There are times when I’m in New York when I’m that famous guy, and I carry the attitude — then I get stopped all the time.” “Sometimes,” he said, he’d use his ‘celebrity’ to “get a decent table at a restaurant.”

At no point in his journey did anybody ask Art Garfunkel why he was skulking around their town. “It just never happened,” however, “I had one incident in Ohio. It was Friday night, and that’s very telling. When the sun goes down on a Friday night, people get a little nutty. There were three guys in a car; they threw a beer can at me; it was three-quarters full and it hit me on the sternum. That was an ouch. I thought I’d broken a bone.”

The interviewer asked him if it was a redneck’s revenge for “Bright Eyes,” but Art didn’t catch the joke. Instead, he replied, “They didn’t recognize me. They were just assholes being mischievous and drunk. It was an Ohio thing.” Nothing much else happened in the Midwest. By the time he reached Nebraska (about halfway through his journey) he was joined, briefly, by journalist Tom Dunkel for Sports Illustrated. The year was 1990.

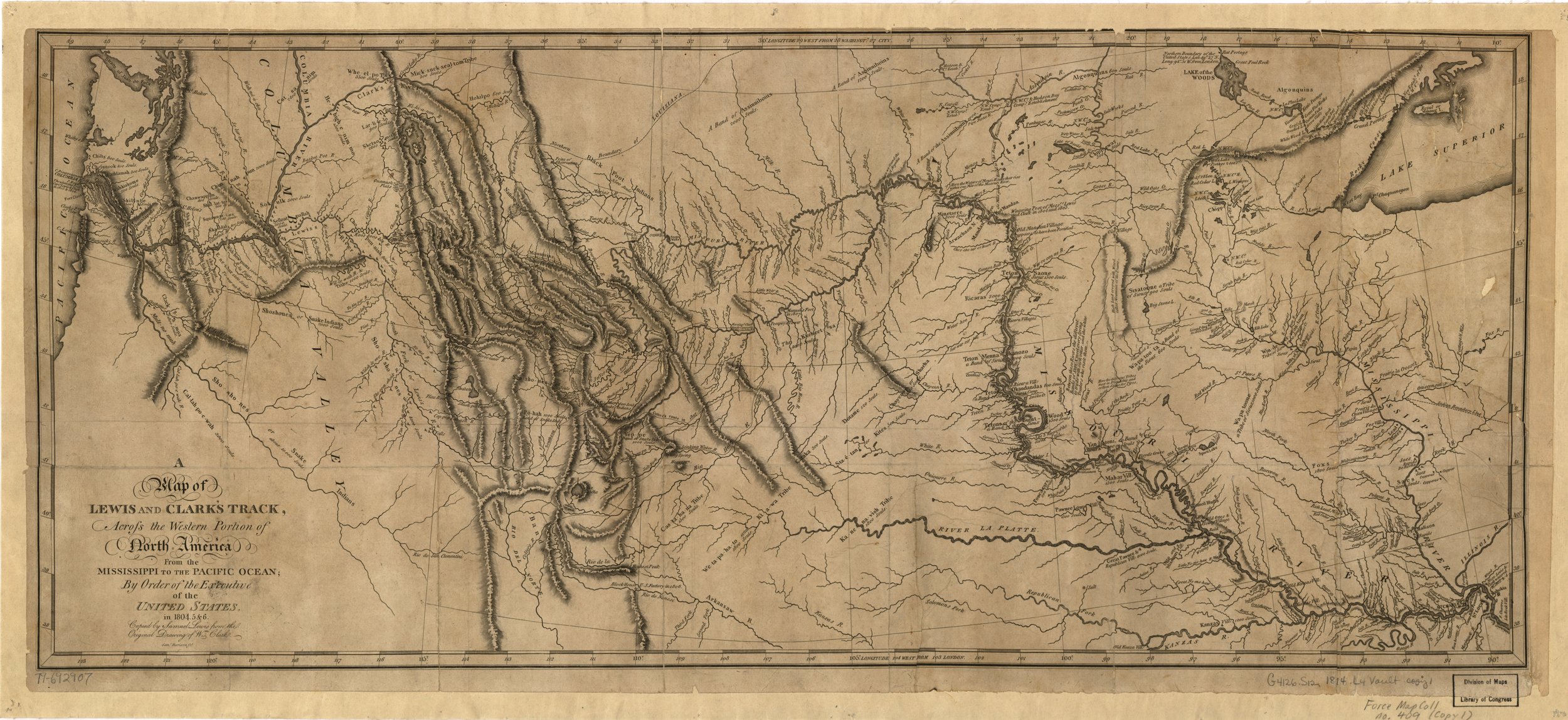

He walks once or twice a year, between April and October, with a map and black pen. “The main thing I'm recording is the topography of the United States—the third dimension; the up and down of everything… I have a memory of every wrinkle in the American landscape now. I really know the East Coast and how the Appalachians began and how they come down ultimately into the Mississippi. It's a sequence of about forty topographical changes,” along the one route he’s traversed. Originally he planned for a precise latitudinal line but, after the Appalachians, he resorted to following state highways. By the time he reached the Rockies, he was tramping the nearly two-hundred-year-old footsteps of Lewis & Clark.

His first steps had been “spur-of-the-moment,” with laced shoes and a heady trot, but the subsequent fourteen years had been meticulously planned (like any of his albums), traveling “rich-man style,” “with an assistant to drive him to the day's starting point, scout lunch and room accommodations, run errands, and retrieve him at the end of the day.”

Art’s aide, Alan Lipson, “who bears a striking resemblance to a short, guitar-playing fellow with whom Garfunkel used to hang out,” drove the journalist west from Omaha—for one hundred and thirty miles—with the performer riding shotgun. Art’s clean, white Reebok sneakers (size nine) pressed against the dashboard and his seat reclined into the back row. Tom Dunkel watched Art lie, arms crossed and blindfold on, humming Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion.”

His pockets held a map, his glasses, a Casio wristwatch, and his Walkman, with cassettes from the likes of Peter Gabriel, pianist Maurice Ravel, and the poems of John Donne (as read by Richard Burton). The self-described loner with a “supple mind” enjoyed the boredom of his cross-country stroll; it gave him plenty of time to be with his favorite person.

Time enough to think, about everything. “I think about what needs to be done. Sometimes it takes the form of those clear fields—singing and acting. Sometimes it takes in a wider range of choices. I'm forced to be a constant philosopher in order to keep defining the meaning of my life” — an endeavor nearly fifty years in the making. “There is a flip side,” wrote Tom Dunkel, “to eleven gold albums' worth of success: the benign curse of too much choice. Garfunkel doesn't have to do anything, so he agonizes over everything.”

In Art’s Manhattan apartment, on the wall of his third-floor study, hangs a large Rand McNally map marked by flag pins for the paths he tread. Displaced for the map were the eleven gold records he accumulated as half of S&G. These trophies now laid on the floor, “propped against the wall,” Tom Dunkel wrote, “sequentially, left to right, from 1965 (Wednesday Morning, 3 a.m.) to 1982 (The Concert in Central Park). They exude an air of casual neglect, like forgotten tombstones of some family that improbably died in chronological order.”

Throughout New Jersey, Art stared at his feet (arguably a better sight than the state) where he had slipped flash cards of Russian phrases into the laces of his sneakers. Beyond the Appalachians, Art would stare at the clouds, imagining shapes within them and wondering what the wind would look like if it were visible. He was ‘Mr. Nobody.’ He was ‘Mr. Question Mark.’ If the rural world was too ambivalent, he would pierce the silence of the Midwestern pastures with Enrico Caruso and Jimmy Webb tunes.

“Herds of cows are mesmerized by me,” he told Tom Dunkel. “I feel like Jesus, walking through a field. I try to do things that read in the cow world. One of them is this,” he said, flapping his arms. “I work them like a politician. If I look sincere, they look very sincere back to me.”

Well before high noon, Tom followed Art Garfunkel to a lone tree on the side of the road, and an idling car. Out from the car stepped Art’s aide, Alan Lipson, carrying a brand new pair of clean, white Reebok sneakers (size nine) for Art to change into. Further up the road, they passed “Arthur Street.” Art smiled; “James Joyce would have loved that. Joyce loved coincidence.”

Tom followed Art for the remainder of the afternoon. As the sun started its descent towards the horizon—the distinct separation between farmland and open sky—they encountered Alan Lipson’s rental car idling on the roadside. Art climbed into the passenger seat, reclined, affixed his blindfold, and told his aide to drive. Alan already had their night’s lodging booked: a motel beyond the local Elks lodge.

Art asked for the window to be cracked, and Alan leaned across him to roll it down. Art inhaled the prairie air. After a pause, he announced to the journalist, “it's not France… but it's a nice country.” His spasmodic journey would end in September of ‘97, at the mouth of the Columbia River, and then he’d go on to walk Europe.

“What will the history books want to record?” Art asked himself, with a hostage audience of two. “In grade school readers, you'll have the Dred Scott case and ‘The Walk.’ People will go, ‘What other walk was there?’ ‘Oh, Lewis and Clark!’ ‘Well, that's an exploratory thing. ‘The Walk’ is the famous Garfunkel walk of the Nineteen-Eighties and Nineties.’”

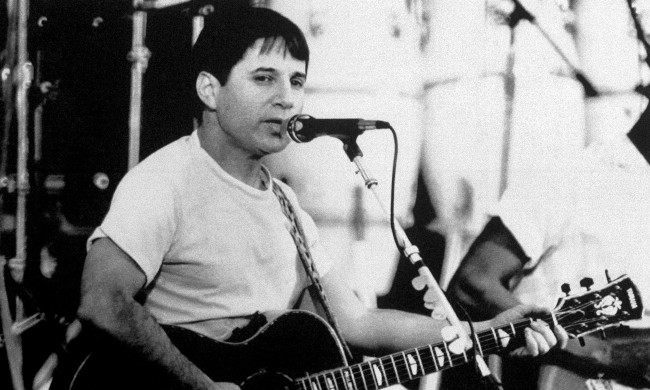

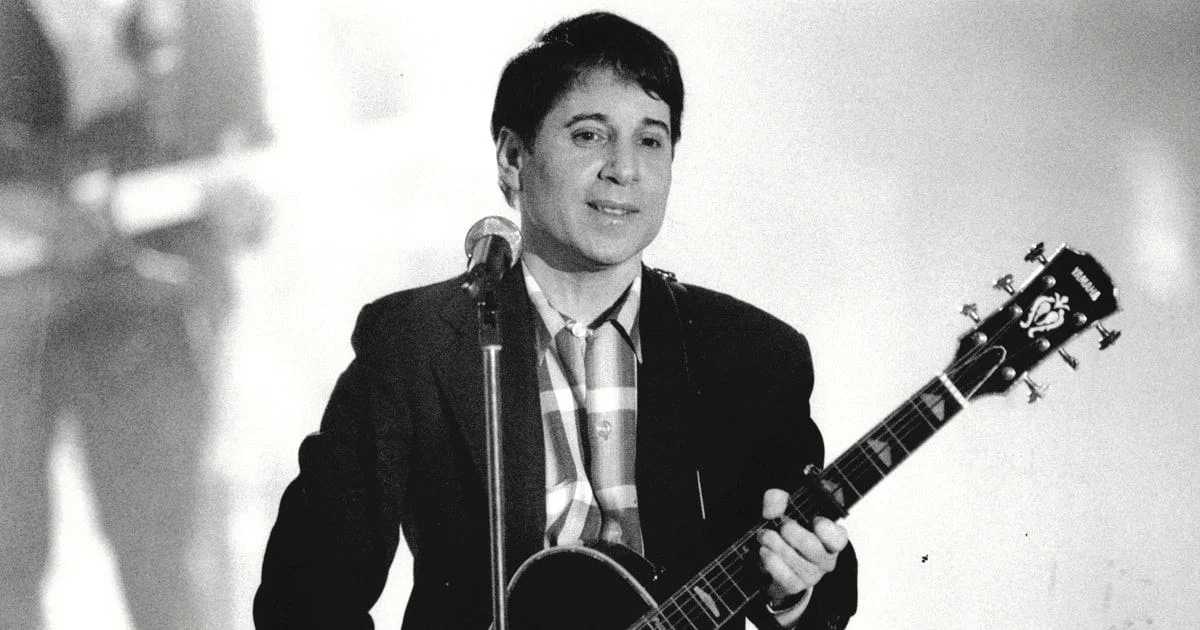

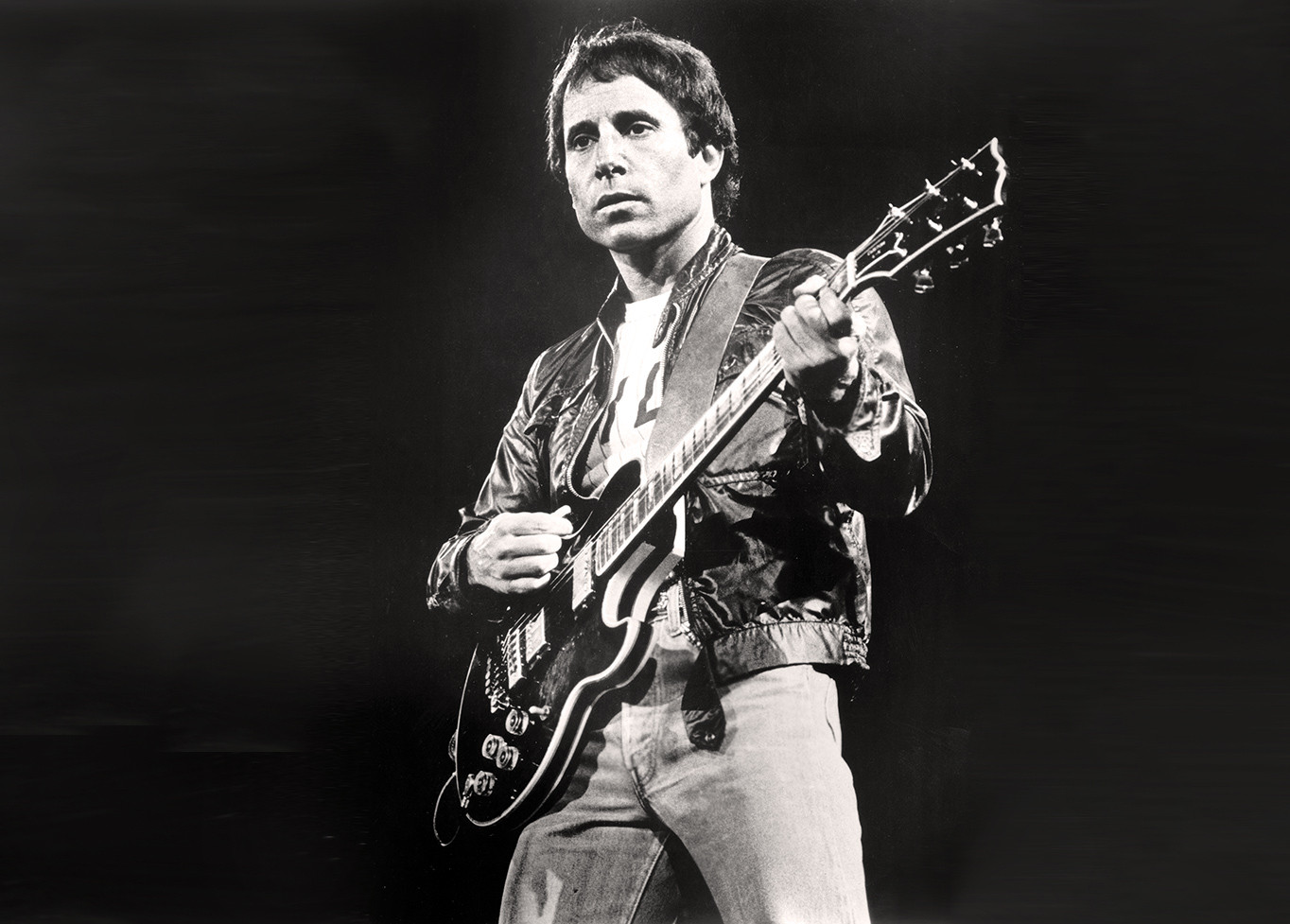

On January 13, 1984, Paul Simon starred as the musical guest (opposite hosts John Candy and Carrie Fisher) on Lorne Michaels’ single-season sketch comedy series “The New Show.” During production, Lorne introduced him to the show’s bandleader, Heidi Berg, who lent him a bootleg cassette of African township music.

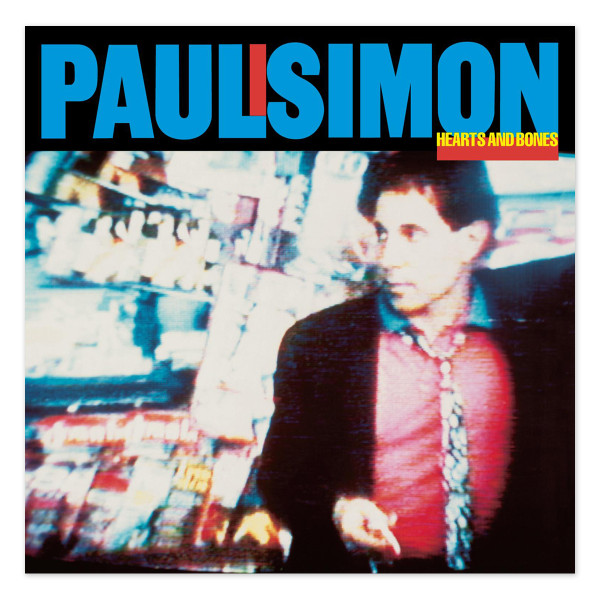

After the dismal reception of “Hearts and Bones” in America, Paul succumbed again to his insecurities. He had just divorced the love of his life, his album wasn't getting any airplay, his well of inspiration was dry, and now it seemed his commercial viability was shot. “I had a personal blow, a career setback, and the combination of the two put me into a tailspin.”

Feeling claustrophobic, and frustrated, he loaded his car and went for a long drive. A few hours in, however, his tape deck cycled to completion. He rummaged in arm's reach for salvation, eventually finding Heidi’s well-traveled cassette in the glove compartment, and he popped it in. To his amazement, he loved it.

It was funky, exotic, rhythmic, and soothing. Reminiscent of the R&B he jived to as a boy, the bootleg instrumental washed away his frustrations and filled him with wonder. He found himself scatting along to the cassette for the remainder of the summer, remembering all the Latin and African rhythms that inspired him in his youth. He had forgone them all for contemporary pop—and for that he felt sorry—but his interest in ‘world music’ had now returned, and his timing could not have been better.

In mid-January, 1985, Paul was one of forty-five artists asked to join in the recording of “We Are the World,” the supergroup single whose proceeds would be donated for humanitarian relief. Singer/activist Harry Belafonte conceived this pop-music fundraiser after hearing about the UK’s ‘Band-Aid’ supergroup and their single “Do They Know It's Christmas?” which strove to finance the feeding of a famished Ethiopia. Belafonte, however, wanted to go bigger: to feed, clothe, and medicate all of the hungry, sick, and struggling communities of third-world Africa.

Belafonte called fundraiser Ken Kragen, who brought two of his clients—Kenny Rogers and Lionel Richie—into the project. Richie called Stevie Wonder and producer Quincy Jones for more “name value.” Jones then called Michael Jackson, who was fresh-off the success of “Thriller,” to help Richie write the song. They took a broad and accessible approach to the “global community/we are but one people” idea.

Kragen, Belafonte, Jones, and Wonder (but not so much Wonder) called around their inner circles of musical superstars until they had a shortlist of some forty-five people, including Billy Joel, Cyndi Lauper, Tina Turner, Huey Lewis, Bruce Springsteen, Steve Perry, Hall & Oates, Diana Ross, Dionne Warwick, Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, Ray Charles, Lindsey Buckingham, Smokey Robinson, The Jackson Five, and Paul Simon.

Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie finished writing “We Are the World” the night before their supergroup was slated to record, on January 21, 1985. On entering the studio, all forty-five pop icons passed under a cardboard sign reading “Please check your egos at the door.” Stevie Wonder met them in the booth. Once everybody was situated on the risers, he made an announcement: if they were unable to record the song in one take, he and Ray Charles would personally drive them all home. (Both Stevie Wonder and Ray Charles are blind.)

“We Are the World” released on March 7, 1985, immediately topping the charts. Its initial shipment of 800,000 sold-out in three days, on to become the most popular record of the year, the first-ever to be certified multi-platinum, and the fastest-selling record of all time. Despite all its popularity, it received largely mixed reviews from critics and consumers alike. One journalist said it sounded like a Pepsi jingle, which wouldn’t have been too hard to fathom, “on the part of Pepsi-contracted songwriters Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie.” Any similarities were “certainly not intentional [yet] certainly beyond the realm of serendipity.” Another critic felt the song was underwritten with a “distasteful element of self-indulgence” as the artists highlighted “their own salvation for singing about an issue they will never experience on behalf of a people most of them will never encounter.”

Still, “We Are the World” was a politically-important milestone in American culture, as it “affected an international focus on Africa that was simply unprecedented.” Stephen Holden of The New York Times noted that “We Are the World” set the standard for ‘popular music’ to address ‘humanitarian concerns,’ as it widened American society’s comfort zone regarding diversity, passively interesting the nation in the idea of African culture influencing their own.

Tickled by the ninety-minute bootleg instrumental, Paul wrote lyrics to accompany a particular track he called “Gumboots” which he then recorded-over at home. This cassette was showing him a new world, and yet he still did not know who recorded it, where they were from, or even what all instruments they were using. It was a fantastic mystery that seemed to hold the answers to some of the questions posed by his midlife crisis.

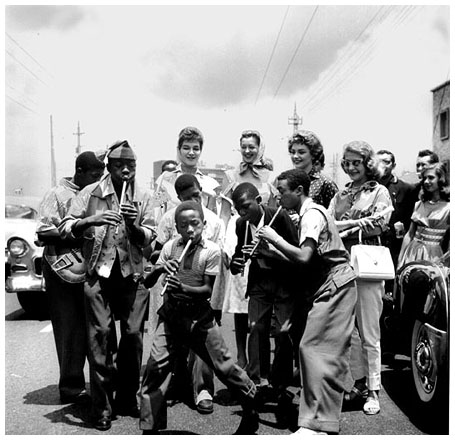

He beseeched his upline at Warner Bros. to investigate the bootleg tape, and within a week they came back with an answer: “Gumboots: Accordion Jive Volume II” by the Boyoyo Boys. They were an established mbaqanga jam band from Soweto, then “the most notorious blacks-only township in apartheid South Africa.” Having earned seventeen gold records in a four-year span, the Boyoyo Boys were what author Evan Fleischer called “expert practitioners” of the mbaqanga genre, known for creating “something as personally appealing and uplifting as a New Orleans second line,” i.e. the parade of revelers that forms behind a brass promenade in the city streets.

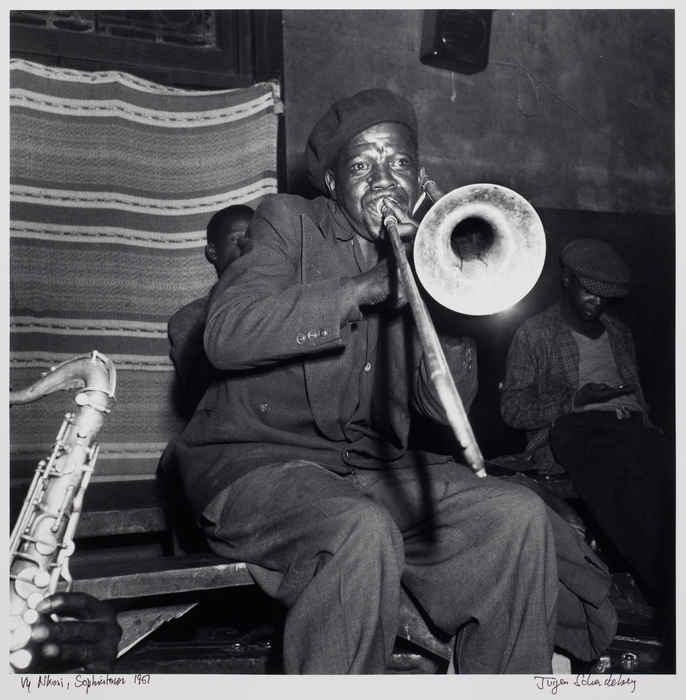

According to Jonathan Greer, the typical mbaqanga rhythm “begins with a brief introduction featuring a ‘rhythmically ambiguous,’ almost…improvised line from a solo guitar.” The bassline follows, and the drums, “setting the beat and establishing a four-bar sequence of chords over which the entire piece will unfold…” A driving saxophone or trumpet then punctuates the rhythm, offsetting and “big,” alongside “call-and-response” vocals among the band, which subsequently influence the direction of the drums and bass for the remainder of the jam.

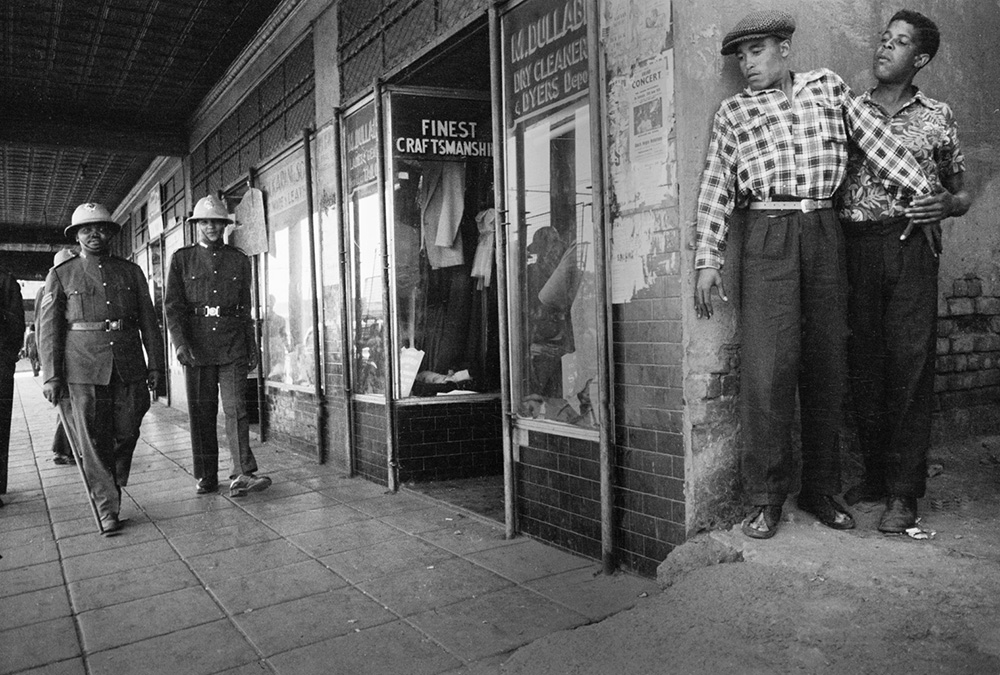

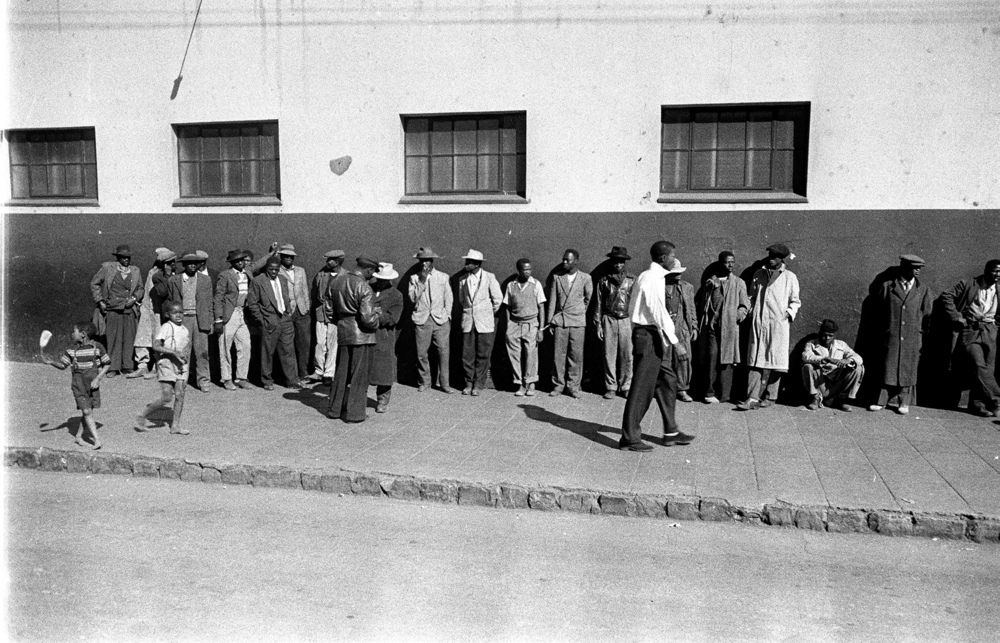

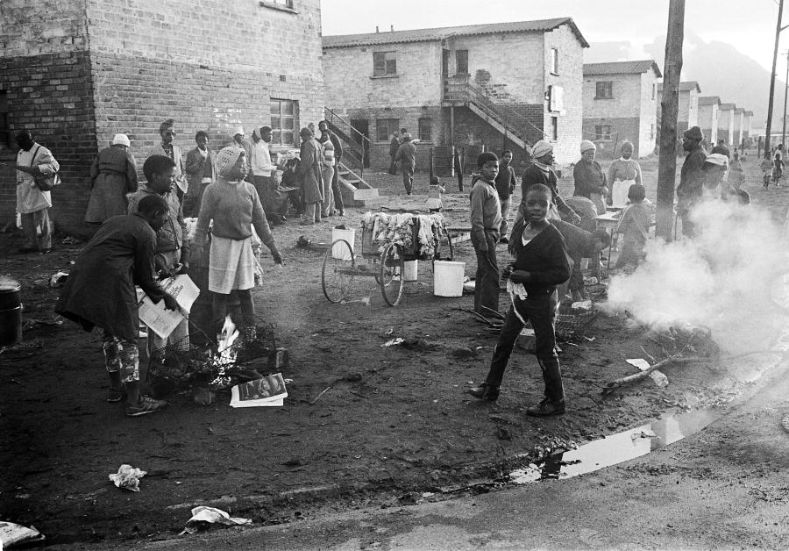

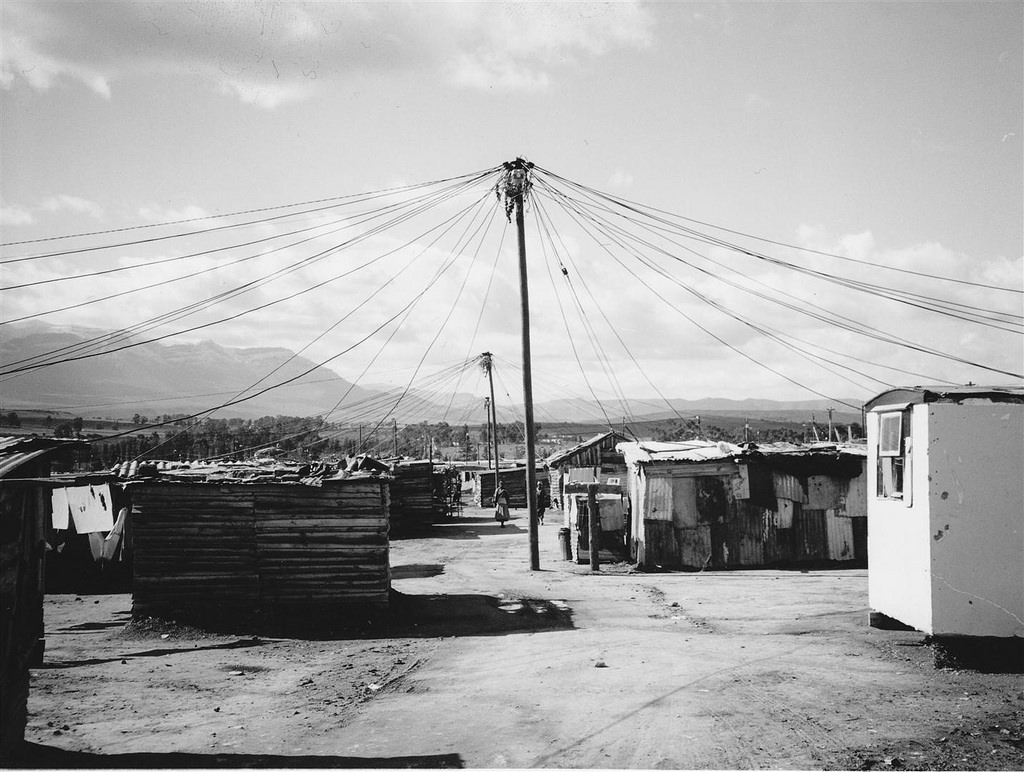

Mbaqanga originated in South Africa in the early 1960s. During the Apartheid era, native Africans were restricted from much of regular society, including career opportunities, forms of expression, neighborhoods, and sides of the street. City-dwelling fans of western jazz music were generally poor and unable to partake in the purchasing, listening, or performing of jazz. However, in the countryside, they could find more freedom.

Using recycled, refurbished, or reattributed western instruments, destitute native Africans could experiment with jazz in the outskirt shebeens — the speakeasies of South Africa. There, communities gathered around a collaborative effort of guitars, drums, brass, double bass, and vocalists galore. Traditional cultural rhythms fed jazz stylings, resulting in a raucous, joyful sound; what the South African government has described as “the cyclic structure of marabi [and kwela vocal styles] with a heavy dollop of American big band swing thrown on top.”

Justifiably, Paul Simon later recalled, “There was the almost mystical affection and strange familiarity I felt when I first heard South African music.” For destitute native communities, such free-flowing musical empowerment was a form of “spiritual sustenance;” a “musical daily bread” to which they attributed the name “mbaqanga” — the Zulu word for their traditional breakfast of cornmeal porridge.

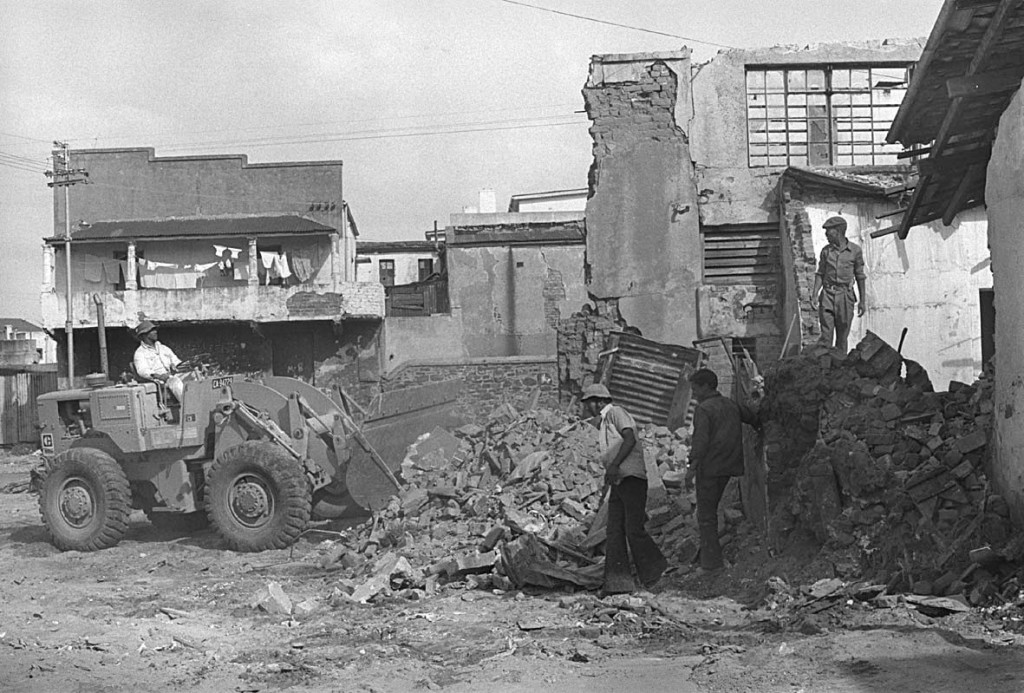

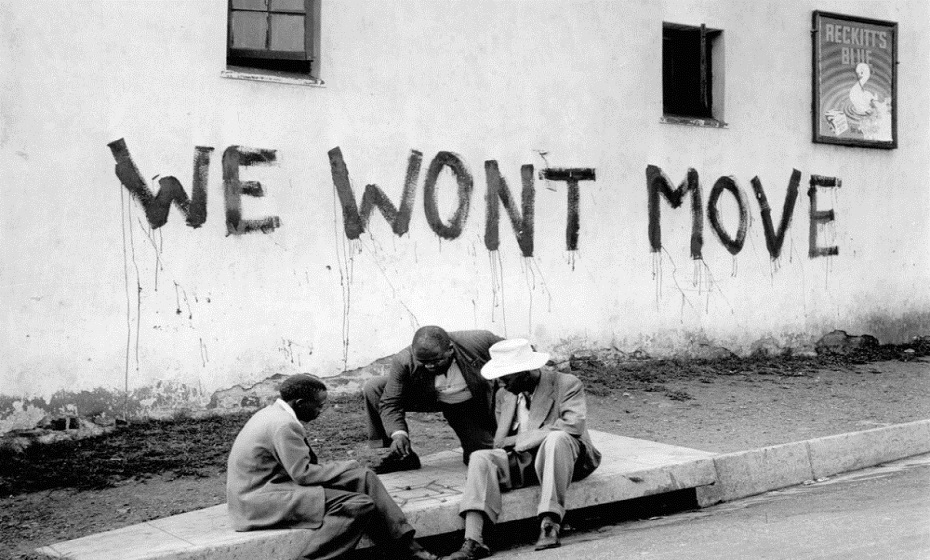

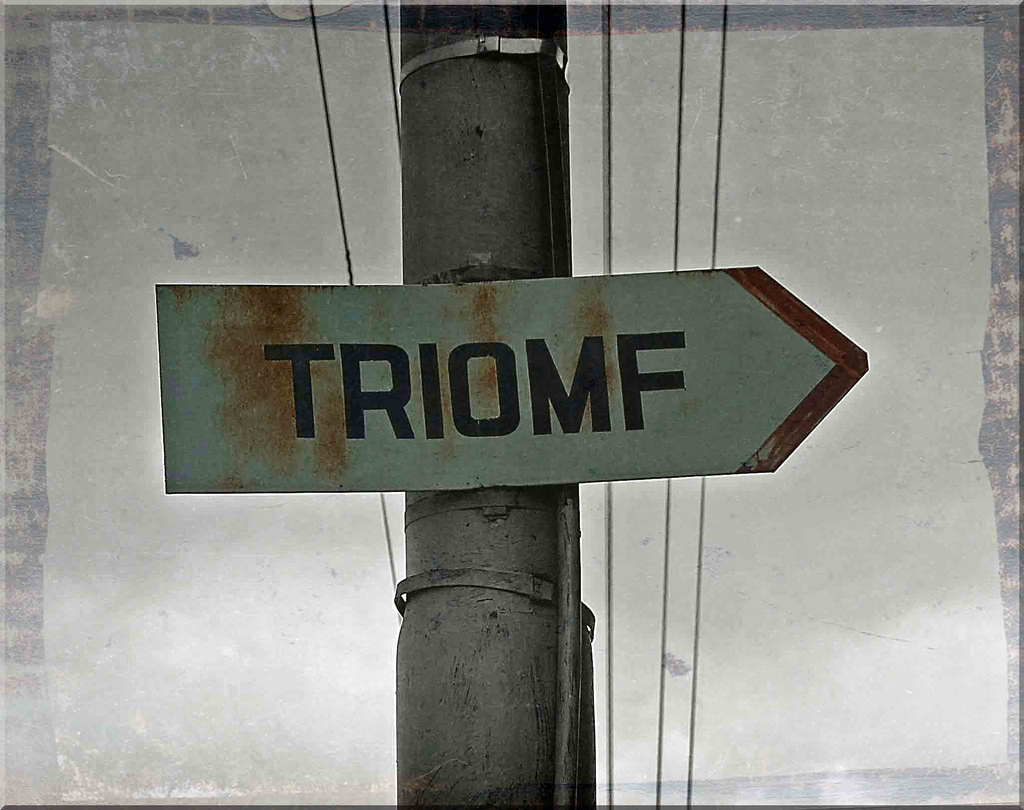

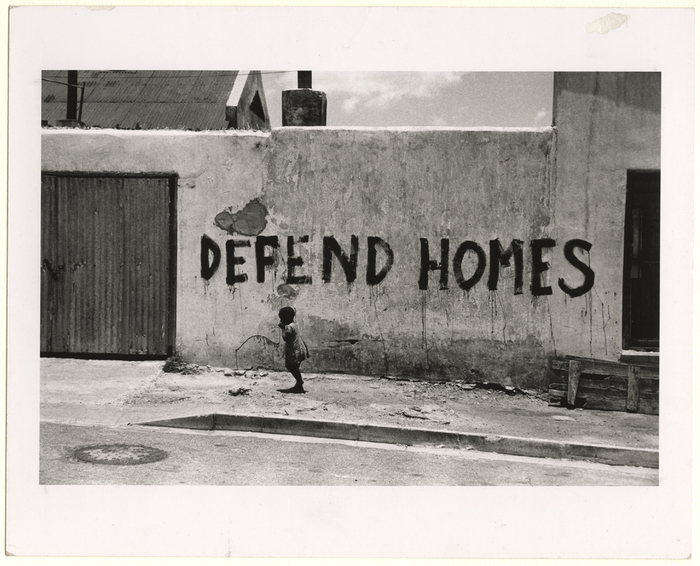

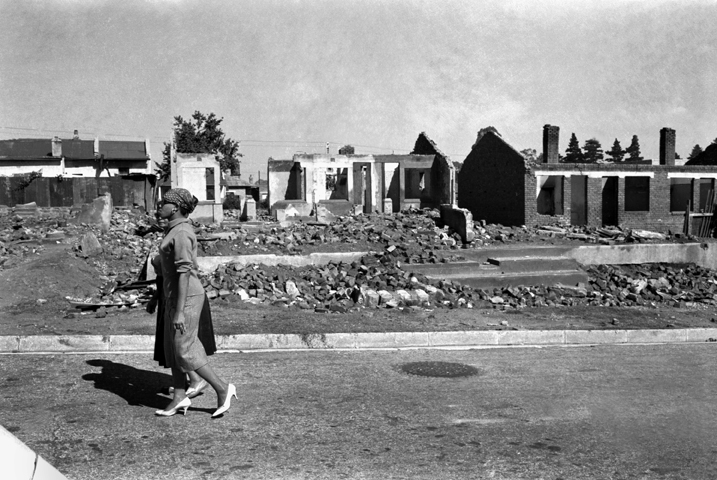

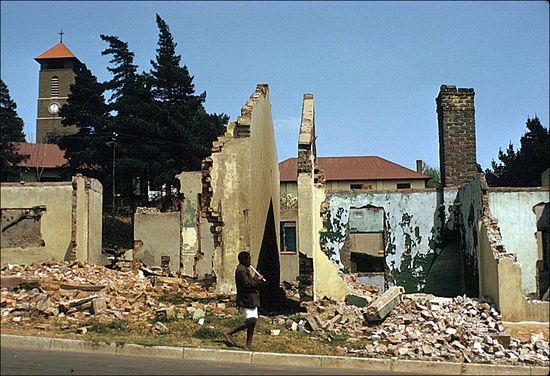

For years, mbaqanga acted as a catalyst for bringing liberal whites and native blacks together in the speakeasies and underground halls of segregated South Africa. The government did not address the deviance of the artform and its venues until it became clear mbaqanga was inspiring resistance to segregation. In a swift offensive, the ‘white nationalist’ military razed the dissenting villages—particularly, Sophiatown, which was leveled and rebuilt as Triomf—and the displaced populous was relocated to the outskirts of Johannesburg, in townships such as Soweto. There, segregation could be more easily enforced, as could cultural repression.

Producer Hilton Rosenthal had grown up in the white suburban half of Johannesburg during the height of apartheid. His parents forbade him from listening to “black music” however, after college, he went to work for the Gramophone Record Co. (South Africa's affiliate of CBS Records) and was soon charged to the “black music” division. He worked against the prejudices of the system to increase the budget, diversity, and publication of traditional Zulu and evolving ethnic music, up into the Eighties.

When Warner Bros. investigated the bootleg tape on Paul's behalf, it was Hilton Rosenthal who supplied the answers. Discerning the intent of the inquiry—to record with a mbaqanga band—Hilton said, “Too bad [the tape is] not from Zimbabwe, Zaire, or Nigeria… Life would have been more simple.” Warner Bros. tried to convince Paul to record in New York, with his choice of session musicians, so as to avoid the red tape of working in apartheid South Africa. However, as with his single “Mother and Child Reunion,” Paul declined, insisting “I need to go there” to get the rhythms from the source.

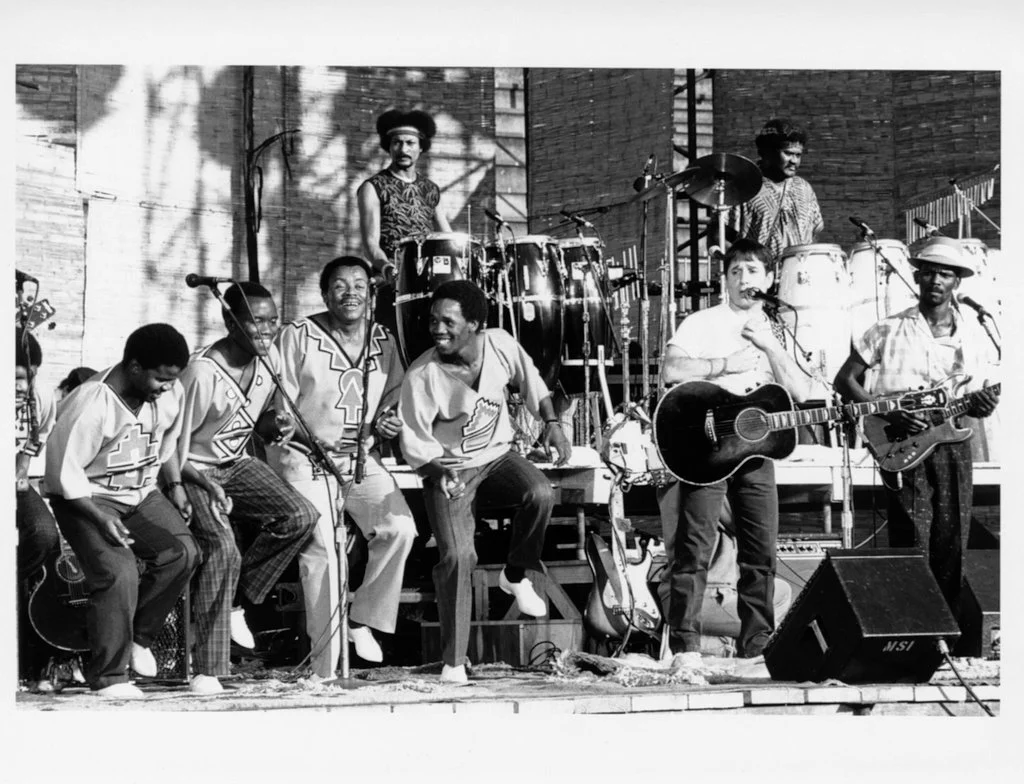

He later told The New York Times, “The search began when my record company, Warner Bros., put me in touch with Hilton Rosenthal, a leading South African record producer, who identified the group on the tape as the Boyoyo Boys. Hilton also sent me records of around a dozen other South African bands. I was so impressed that I inquired whether it would be possible to record with some of them. I found that I could. And in February 1985, I flew with the recording engineer Roy Halee to Johannesburg.”

Paul had brought Roy Halee back into the fold of his studio career. In fact, Roy was the first person he reached out to about recording an album inspired by “Gumboots: Accordion Jive Volume II.” As Roy recalled to Richard Buskin in 2008, “For me, that project started with Paul telling me, ‘Roy, I've got to play you something that is just great.’ It was the most infectious thing I'd ever heard; as catchy as hell. He said, ‘We have to go over there and record it.’ I said, ‘Where?’ ‘South Africa.’ ‘Okay, great.’”

“Hilton knew everybody in Johannesburg, and so he was able to garner all of these musicians who we'd never previously seen or even heard of. He also booked the recording sessions at Ovation, where they'd mostly been doing South African gospel, and that was a good studio. I remember walking in there and thinking, ‘This is the best-sounding control room I've ever been in.’ … I'd expected a horror show, but everything worked and my first impression was, ‘This is very comfortable.’” It was almost “like you were in your living room… Having said that, the studio itself was like a garage, and in that regard I thought it could be a problem, especially since we were going to record jam sessions from which songs would be created.”

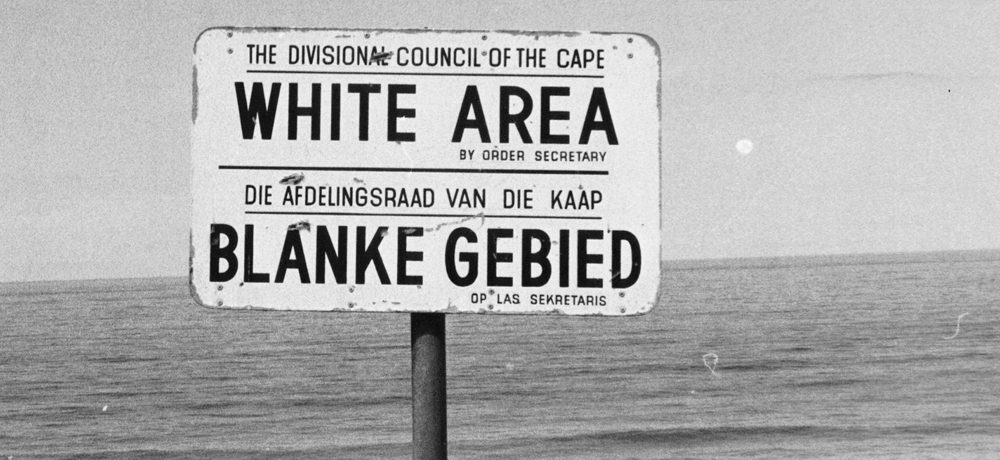

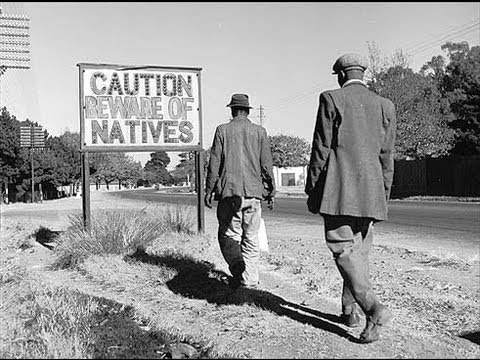

The ‘horror show’ Roy expected had actually been outside the studio, in the streets, and in the air. The hesitance Warner Bros. expressed before sending Paul Simon to South Africa was owed to the western world’s standing boycott on the country. The South African government, helmed by the descendants of British and Dutch colonialists, were fiercely upholding ‘apartheid’ — a network of institutionalised racism by way of segregation. In Afrikaans, “apartheid” literally means “separateness.”

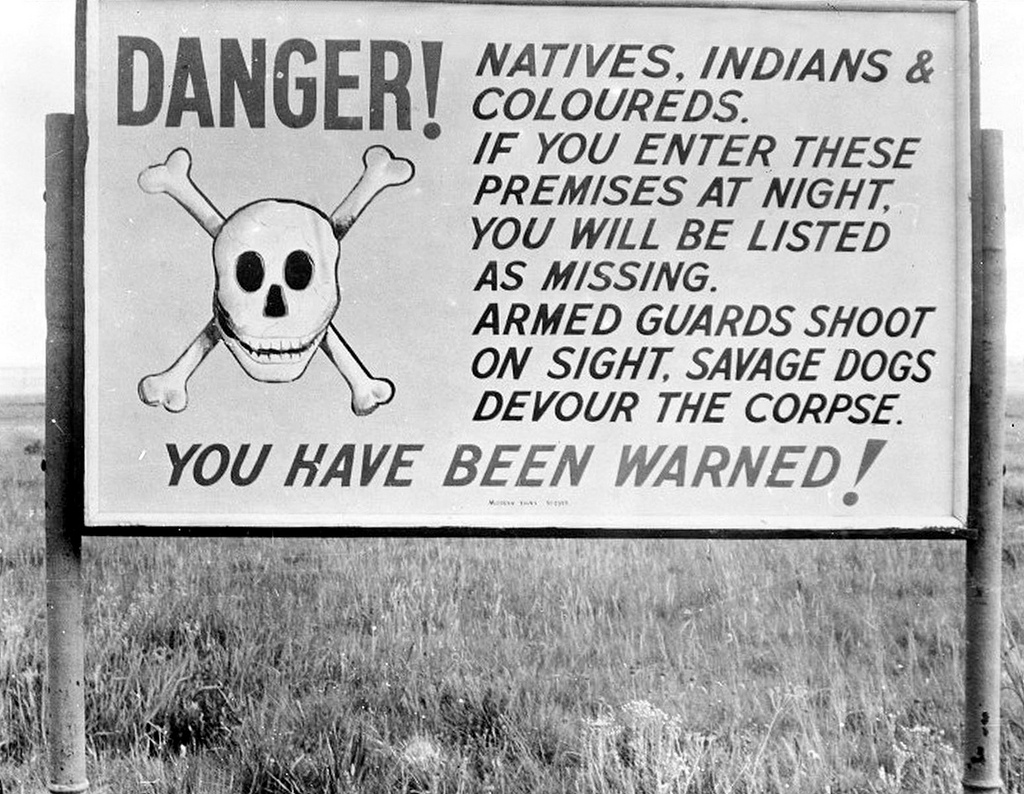

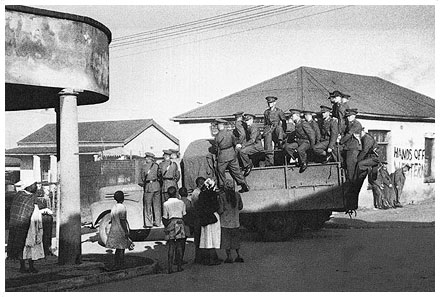

The authoritarian white minority, under the ideology of baasskap (‘white supremacy’), ensured the repression the native black populous for over a century, though institutionalised ‘apartheid’ only officially began in 1948, with the election of the National Party. The distinction was the codifying of racial separation, in realms as petty as drinking fountains and cinemas, and as substantial as housing and employment. Segregation was socially and federally enforced, to the point of entire swaths of land being deemed “off-limits” to “coloreds.”

The British had taken South Africa from the Dutch Empire in the Second Boer War, at the turn of the century, and they retained all of the industrialised systems: the port, the railways, and the racism. In fact, racial segregation worsened under British rule. After their National Party won the election of 1948, they passed the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, the Immorality Amendment Act (restricting interracial dating), and the Population Registration Act (designating four racial types: ‘Black,’ ‘White’, ‘Colored’, and ‘Indian’) through which they could stratify neighborhoods. However, as the cities grew, these areas had to be expanded.

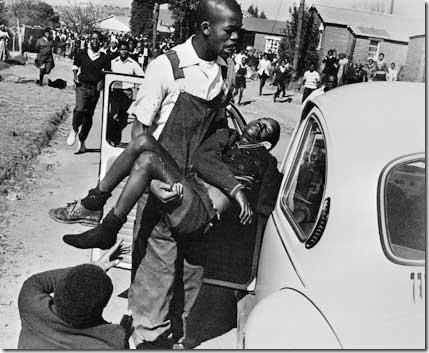

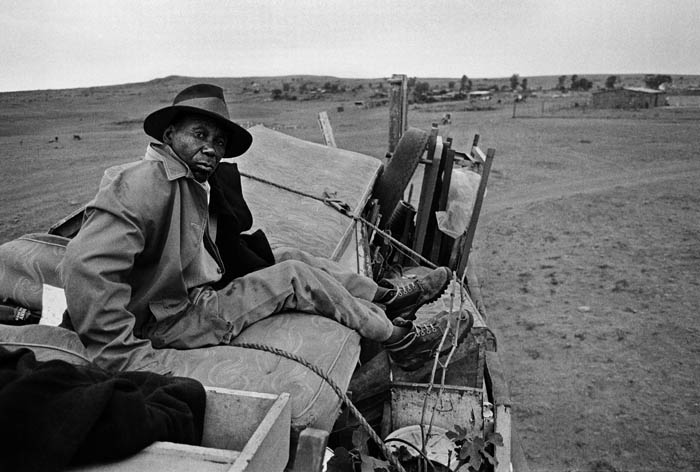

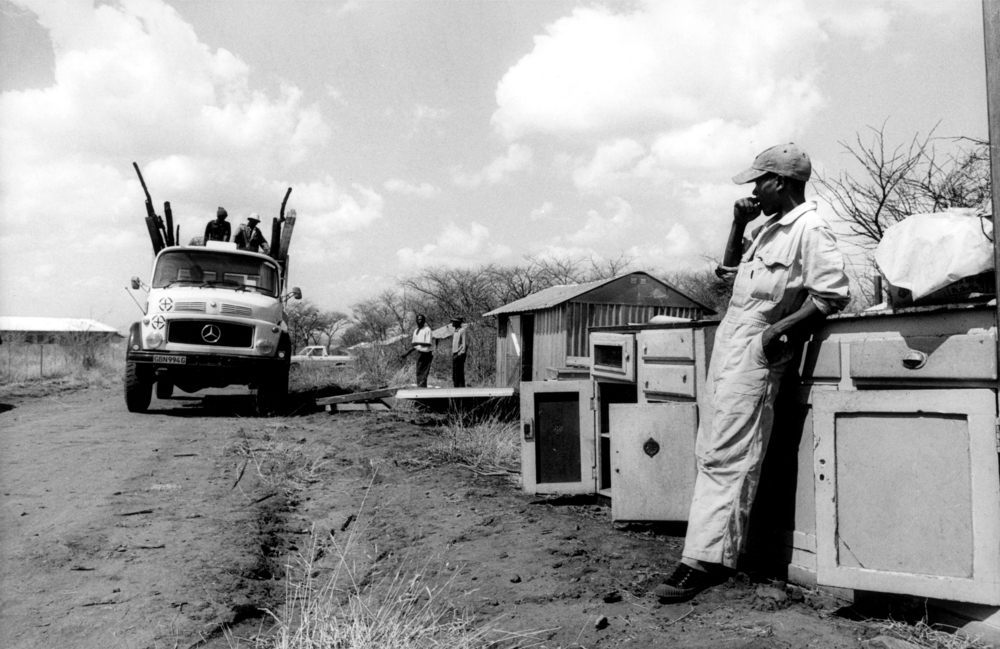

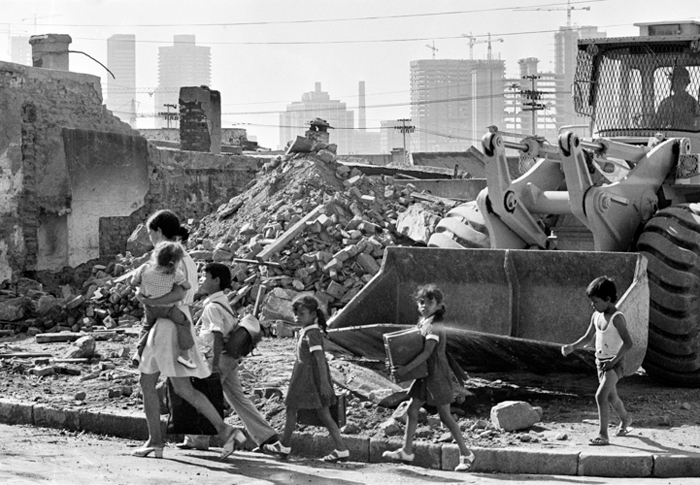

Between 1960 and 1983, 3,500,000 non-white natives were expelled from their homes and relocated en masse to ten distant ghettos, under the guise of “returning the natives to their ‘tribal homeland.’” Those who relocated to these “bantustans” were required to surrender their South African citizenship and the few perks that came with it (e.g. plumbing, electricity). Naturally, nobody was enthusiastic about moving to the bantustans, but they didn't have a choice.

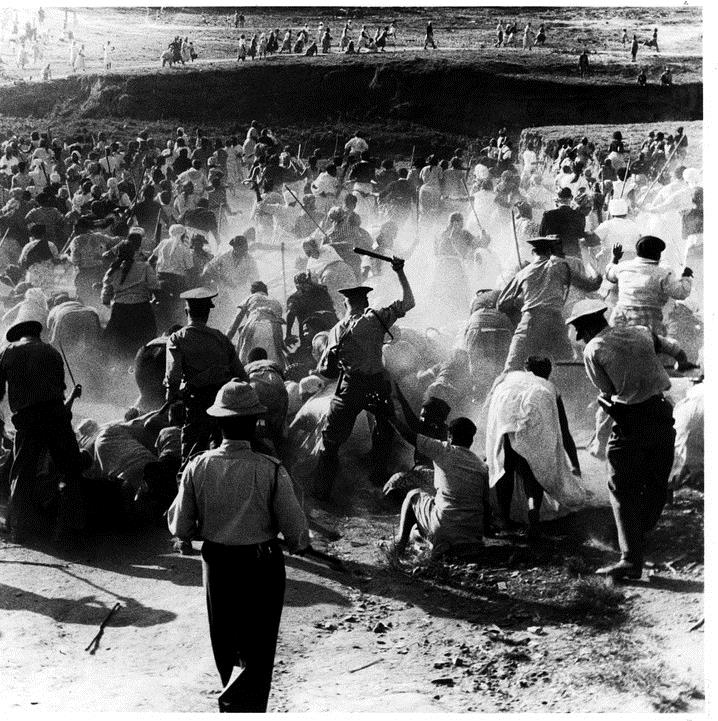

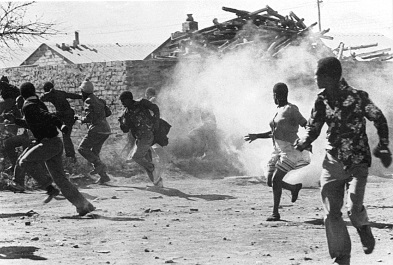

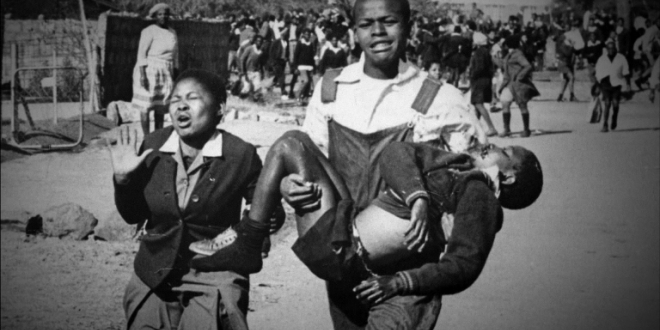

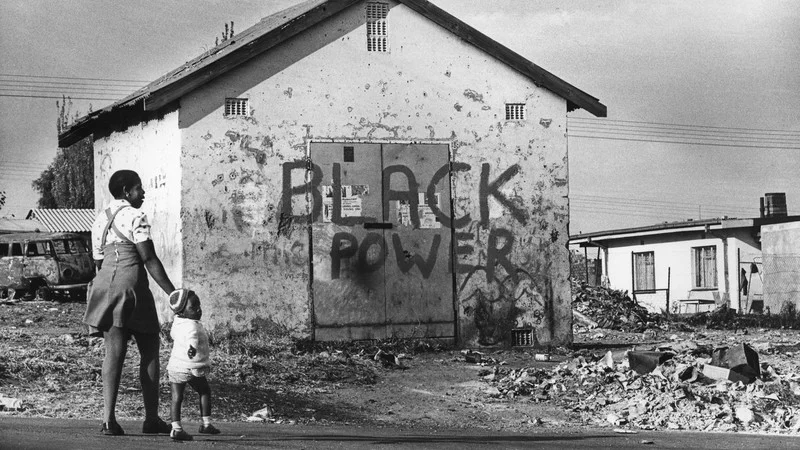

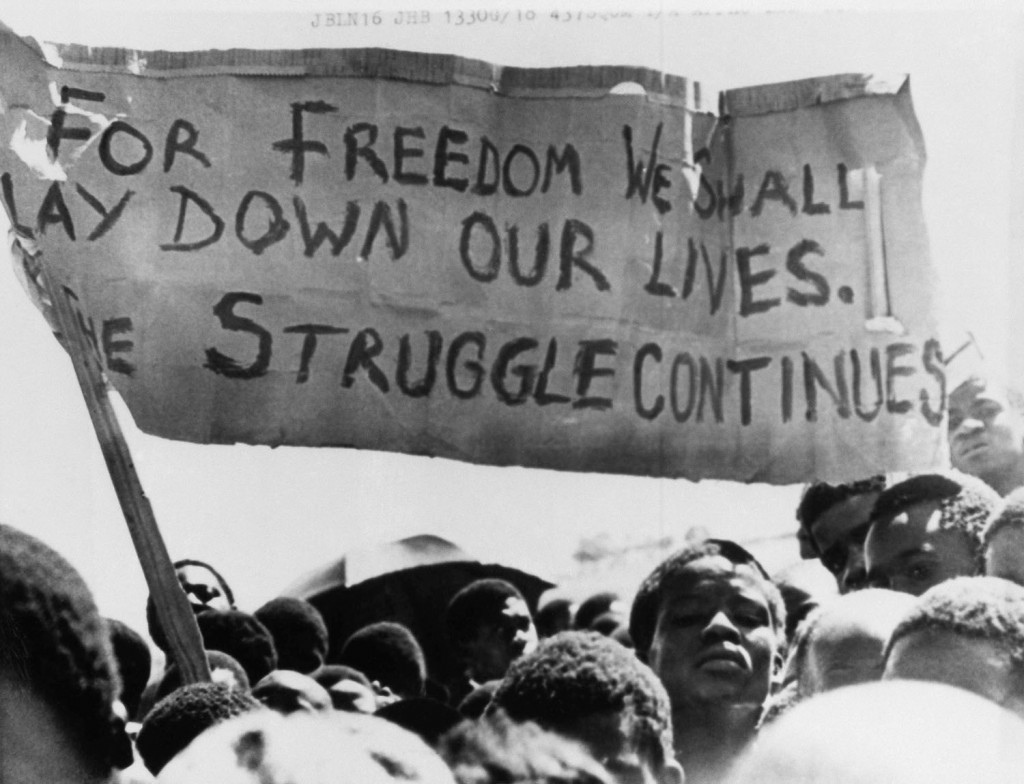

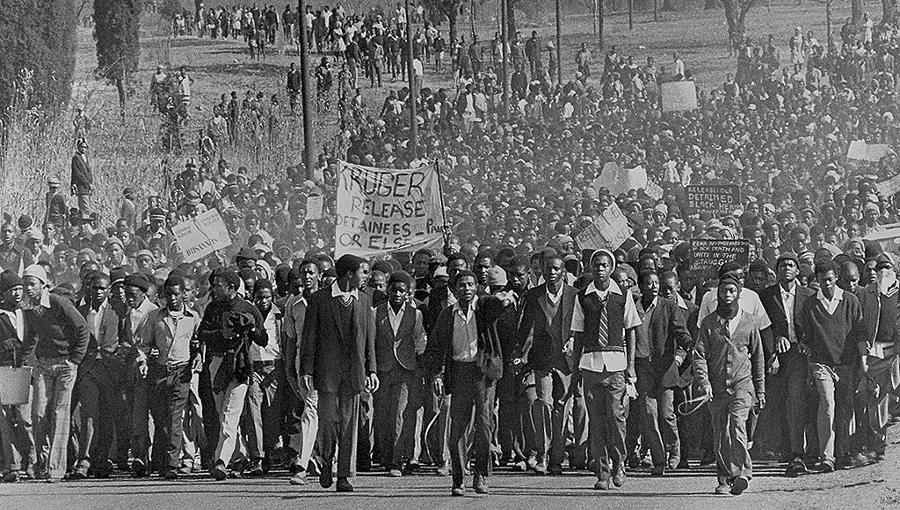

The 1970s saw a rise in resistance to the evictions, segregation, and racism of apartheid, and the South African government responded with gratuitous militant force. Thousands died and countless others were incarcerated, prompting the United Nations to raise an armaments & trade embargo against South Africa. Such global pressures forced the National Party to negotiate with the African National Congress, from 1987 to 1993, resulting in an end to apartheid. — Unfortunately, we are not there yet in our story.

The year is 1985. Apartheid is at its most violent peak. All Western & European nations have broken their relationships with South Africa, thereby allowing the economy to falter and the racial strife to swell. The native blacks and the white minority are on the brink of a civil war—if not considerably already in one—and Paul Simon chose now, of all times, to visit.

Paul was understandably nervous about his upcoming trip to South Africa. “There were people who said I shouldn't go,” he told The New York Times. “South Africa is a supercharged subject surrounded with a tremendous emotional velocity. I knew I would be criticized if I went [but] I was following my musical instincts in wanting to work with people whose music I greatly admired.” While recording “We Are the World,” he spoke with two of the song’s organizers, Quincy Jones and Harry Belafonte, on the morality of breaching the boycott. Jones and Belafonte were in agreement: this mission was noble and necessary, to be undertaken ‘because of’ rather than ‘in spite of’ the nation’s political tensions. A show of racial cohesion for cultural benefit could only have a positive outcome.

Before leaving for Johannesburg, in February 1985, Paul secured the approval of the Musicians Union of South Africa. “I later learned [they] took a vote as to whether they wanted me to come. They decided that my coming would benefit them, because I could help to give South African music a place in the international musical community similar to that of reggae.” The union promised to defend him from condemnation and censorship during his endeavor, as all parties knew he would draw criticism from both pro- and anti-apartheid affiliates.

Having grown-up on the brighter side of apartheid, Hilton Rosenthal was acutely aware of the troubles Paul would face, and he tried his best to streamline the visit. He mailed Paul twenty vinyls of South African musicians—mbaqanga bands and isicathamiya choruses alike—for Paul to consider working with on the record. He listened to each the vinyls and, of his preferences, Hilton arranged for over a dozen black musicians to meet at Ovation Studios in Johannesburg. Paul was most-excited to meet the Boyoyo Boys but, unfortunately, they were tied-up in a legal battle with Malcolm McLaren, the former manager of the Sex Pistols.

McLaren had pilfered the Boyoyo Boys’ track “3 Mabone” to underlay a hit single of his own, “Double Dutch,” and he was refusing to award them royalty payments. The Boyoyo Boys eventually settled out of court and, two decades later, Malcolm McLaren acquired peritoneal mesothelioma—a rare form of cancer that besieges the soft tissues lining the contents of the abdomen, sludging the lubricating fluid that maintains your organs the same way oil maintains your car engine. He died a slow and painful death, likely bestowed by karmic forces for his lifetime of being an exploitative egoist and heartless ass.

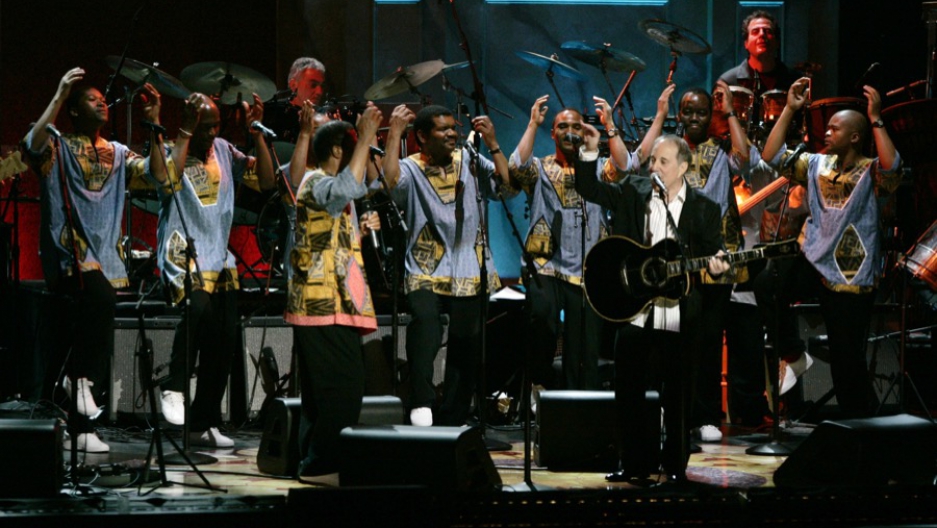

The majority of the musicians made their way to Johannesburg from the ghetto of Soweto. The caravan included Lulu Masilela, Joseph Shabalala, and members of Stimela, Tau Ea Matsekha, General MD Shirinda & The Gaza Sisters, and Ladysmith Black Mambazo. Paul quickly found syncopation with Tau Ea Matsekha’s Bakithi Kumalo on bass, Stimela’s Isaac Mthsli on drums, and Chikapa “Ray” Phiri (also of Stimela) on lead guitar. As Roy Halee recalled, “the guitarist, Ray Phiri, always had a wealth of stuff going on in his head. He was smart, he could tell what Paul liked, and he would just go into the little catalogue in his mind and come up with something. Of course, he played guitar on everything.”

“Whenever Paul said, ‘What do you have, Ray?’ the response would be, ‘Well, I have this…’ He's a really quiet, unassuming gentleman, and yet he was the catalyst for so much that took place, along with the bass player Bakithi Kumalo. Bakithi is now world famous, but back then he was just a kid from Soweto… He was unbelievable. For me, those sessions were all about the bass. It always seemed so powerful, and whenever Paul and I came back to New York and listened and listened and listened to the material, it was the bass that really turned me on… And you should hear some of the outtakes. Even today, there could be two instrumental albums consisting of those fabulous grooves.”

“As I soon found out, the musicians liked to work very close together, with eye contact to get the feel and the groove going… Nobody wore headphones, aside from the drummer, and even he often didn't wear them… Well, I wasn't about to get into that with these people. They were to come in, play, and feel comfortable, while my job was to get some isolation… In my opinion, the musicians have to be comfortable and able to see each other. The drummer in his own little room with headphones just doesn't make it for me…”

“For my part, I have good ears, and on this album I had a lot of input, but this was [Paul’s] baby. He heard this. I wouldn't have dreamed about going to South Africa…” As if to prove himself a musical genius, Paul Simon had visualised a cohesive album incorporating the styles of pop, rock, zydeco, a cappella, isicathamiya, mbube, and mbaqanga—and he recorded everything at the source, with the largely-unknown mavens of the genres.

“Paul is a master organizer,” Roy told Richard Buskin. “He was great at determining which section would be nice as a bridge or a chorus or an intro while striking up friendships with the group members with whom he could communicate.” “That's how the songs really evolved. Paul has great musical ears, and when it came to sifting through all the material and deciding what to use, where to make edits, and how to shape things into a track, he had a lot of that in his head. He has an incredible mind, and there wasn't anything that he didn't make a mental note of while listening to the musicians play their grooves. Paul Simon is one in a million. Once you work with him, you don't want to work with anybody else.”

For twelve straight days, Paul and his baker’s dozen recorded a series of jam sessions, each ranging between ten and thirty minutes in length. “Paul certainly wasn't going to tell those guys what to play,” Roy explained. “The sessions had to take place within certain hours before the bus came to take them all away.”

In a 2012 interview with NPR, Paul recalled one evening when he was developing “Gumboots” with saxophonist Barney Rachabane: They were close to finding the right groove for Rachabane's solo but Rachabane had to stop for the day; it was nearly five o'clock and Rachabane “didn't have a permit to be outside that late.” Paul said this moment, among others, really put into perspective “the incredibly tense racial environment, where the law of the land was apartheid.”

As you'd expect, tensions always ran high in the studio; the public outside were largely antagonistic towards the black musicians and the Americans who dared fraternize with them. Paul wanted to prove his gratitude to his fellow musicians, and he paid them triple their union rates ($196.41 an hour) in addition to writer's credit and royalties for any stand-out melodies if they formed the backbone of a song.

These two weeks, Paul recalled, were “one of the greatest times of my life. Real, great fun and experimentation, and learning; meeting great people and musicians.” “There was the visceral thrill of collaborating with South African musicians… Add to this potent mix the new friendships I made with my band mates, and the experience becomes one of the most vital in my life.”

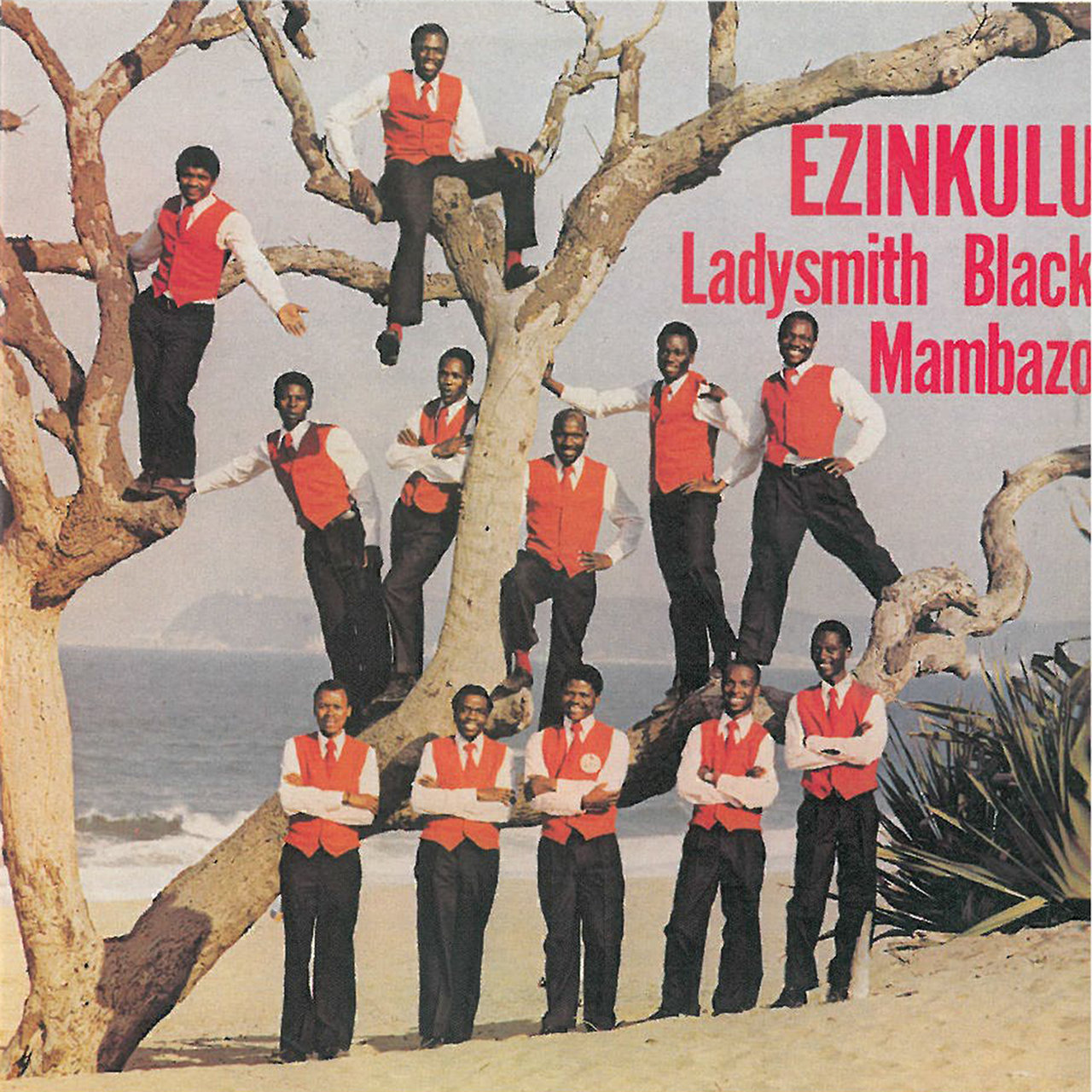

The group Paul collaborated most prevalently with was the nine-man a cappella choir Ladysmith Black Mambazo. Loosely translated to “the black axe from Ladysmith Township,” the Ladysmith Black Mambazo were formed in 1964 on the dreams of Joseph Shabalala—literally. Shabalala once had a series of dreams in which he heard the traditional isicathamiya harmonies of the Zulu people. Inspired, and with little prior experience, he composed a thirteen-member outfit from the ashes of a men's chorus. They performed at weddings, refined their sound, and were inevitably banned from all local competitions for being “too good.”

Ladysmith Black Mambazo released their first album in 1973, which went gold, and subsequent successes paved the way for their collaboration with Paul Simon in 1985. By this time, they were renowned for their mastery of the local vocal style of mbube and its tighter derivative isicathamiya. After working with Paul, the harmonious flavors of Joseph Shabalala and Ladysmith Black Mambazo found international acclaim, followed by five Grammy Awards.

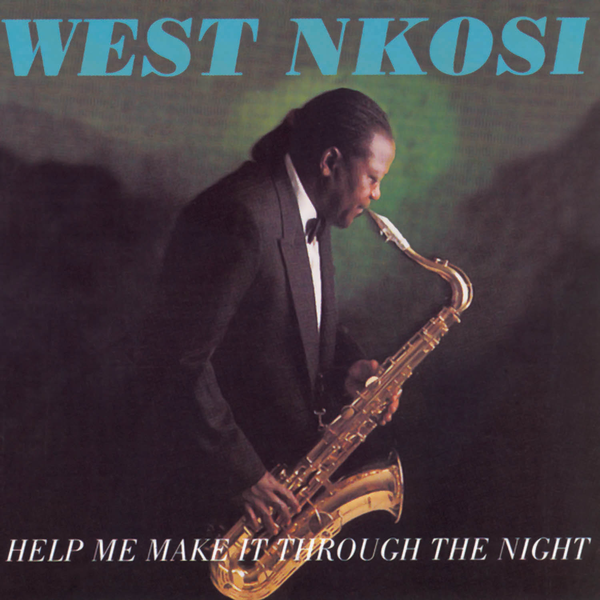

Their genesis was owed to Shabalala, and their prominence was owed to Paul Simon, but their growth was owed to their manager, West Nkosi, who produced their first twenty-two records and arranged for the group to be among those chosen by Hilton Rosenthal for Paul's 1985 South African sessions. After Ladysmith Black Mambazo found international fame, in ‘86, Nkosi wiped his hands of the choir—a mission accomplished—and he returned to his first love: the saxophone. He released the critically-acclaimed “Rhythm of Healing: Supreme Sax & Penny Whistle Township Jive” in 1993. Five years later, a horrific car accident left him paralyzed, and he died within a few weeks—heartbroken and invalid—at the age of 58.

“What I was consciously frustrated with,” Paul told Billboard magazine, “was the system of sitting and writing a song and then going into the studio and trying to make a record of that song. And if I couldn’t find the right musicians or I couldn’t find the right way of making those tracks, then I had a good song and a kind of mediocre record.”

“With these musicians, I was doing it the other way around. The tracks preceded the songs. We worked improvisationally. While a group was playing in the studio, I would sing melodies and words — anything that fit the scale they were playing in.” There were no arrangements; there were no songs; there were only the musicians, their instruments, and their inspiration. They played what felt right, in jam sessions, and—after recording hours of tape—Paul and Roy Halee went back to Manhattan, cut the jams into tracks, and Paul wrote lyrics over the music.

The lyrics came from the tonal patterns of the jam tracks, which meant identifying portions of improvised music that could become verses, choruses, and everything else—almost like making a documentary out of home video footage you found in a box under a park bench. “It was very difficult,” Paul said, “because patterns that seemed as though they should fit together often didn't. I realized that, in African music, the rhythms are always shifting slightly and that the shape of a melody was often dictated by the bassline rather than the guitar. Harmonically, African music consists essentially of three major chords—that's why it sounds so happy—so I could write almost any melody I wanted in a major scale. I improvised in two ways: by making-up melodies in falsetto, and by singing any words that came to mind down in my lower and mid range.”

As the songs were assembled in parts, the larger theme of the album eluded him. He kept a stack of yellow legal pads in the studio and jotted hundreds of words and phrases that came to mind when listening to playback. One phrase, “driving through wasteland,” morphed into “going to Graceland,” which held some spiritual truth for Paul: traveling to Africa, where mankind laid its first rhythms, and then returning to America, birthplace of rock ‘n’ roll.

His album was to be a blend of humanity's musical roots and its most recent revolution, amalgamated from the product of musicians surrendering themselves to the moment; to the union; to the harmony. The New York Times called it “the rock album equivalent of a work of literature.” Paul felt similarly, saying, “I think of writing an album as like writing a play. As in a play, the mood should keep changing. A serious song may lead into an abstract song, which may be followed by a humorous song. On ‘Graceland,’ I tried to be more accessible than in the past without giving up the language.”

It was a word that refused to leave him throughout the processes of cutting and songwriting—GRACELAND—and it became the heart of the album. “It wasn’t about Elvis, but that word wouldn’t go away,” and he's glad it didn't. ‘That word’ took on a greater meaning: “Graceland, to me, is a learning experience of—a uniquely elevated period of my life, musically, politically—of growing up… It’s the grace that I got.”

“The lyrics, in turn, caused a big problem,” Roy confessed. “A lot of the album's songs are very wordy—they come at you like gangbusters—and the arrangements were also involved, but at the same time it was supposed to be a pop record and people had to understand the lyrics. That was tricky, both for Paul to enunciate them and for everyone else to hear them.”

“Capturing Paul's vocals was always very, very tough. Not because of his ability, but because he's a perfectionist… so he would go out and sing the same vocal fifteen times and then I'd comp like crazy. I'd say, ‘Let's do this line over,’ or, ‘This word sounds a little sharp,’ and so he'd re-sing the entire song just so that I could quite literally take that word.”

“The amount of editing that went into that album was unbelievable,” he said, referring to the arduous transference of analog tape to the ‘new’ digital workstation. “Without the facility to edit digital, I don't think we could have done that project.” “We recorded everything analog, so it sounded really good,” but manually editing hours and hours of analog tape would’ve taken ages, so Roy transferred everything to digital, “edited like crazy, put it back on analog, took it to LA to overdub Linda Ronstadt or whoever, brought it back to New York, put it back on digital, and edited some more. We must have done that at least twenty times…”

Editing and re-recording was done in Manhattan, LA, London, and Louisiana, while most of the songwriting was done in solitude at Paul’s beachside home in Montauk, at the far tip of Long Island. There, he played the jam tracks backward as often as he played them forward, searching desperately for patterns. As Stephen Holden wrote in The New York Times, “one gets the sense of an artist submitting to, and being swept up by, musical forces he does not totally understand. Adding a crucial extra dimension to the album is Mr. Simon's very urbane literary sensibility… For Mr. Simon, a normally somber composer-lyricist, the merging of the two cultures has yielded music of astounding joy and playfulness and prompted zany, many-layered pop lyrics that embrace the world in all its terror and confusion.”

Paul invited a dozen American musicians to contribute to the album — most notably, his childhood idols, the Everly Brothers, who sang background vocals on the title track. “Some time after I had finished the tracks for eight songs,” Paul remembered, “I went on a trip to Louisiana with the composer and saxophonist Richard Landry… [There] I realized that the accordion, which had been so prominent in African music, was also integral to Cajun music… At a dance hall in Lafayette, I saw the group Good Rockin' Dopsie and the Twisters, and we went to a little studio behind a music store in Crowley and recorded the song that became ‘That Was Your Mother.’ Then I contacted the Mexican-American band Los Lobos in Los Angeles, and we recorded what later became ‘All Around the World or the Myth of Fingerprints.’ Los Lobos' music also features an accordion. And so the accordion became my connection back to America.”

“Throughout the Graceland project,” Roy Halee recalled, “I tried to capture the integrity of the South African sound—not my own sound—and managed to pick up some of their very interesting ideas. One of these was that they'd use a small amount of very short chamber to the bass, and it was great. It worked very well with Baghiti's fretless bass. I put all kinds of tape reverb and delay on the synth bass line to make it do more than it was actually doing…”

“They almost threw me out of Columbia Records for doing that type of thing. I had machines lined-up all the way down the hall, using tape reverb and delay on different Simon & Garfunkel recordings, like ‘Mrs. Robinson.’” Paul had his two-cents for each edit, and though “He's usually right,” Roy conceded, “if I'll tell him something's out of tune, he'll just say, ‘Fix it,’ and leave me to it. That takes a lot of trust.”

Pierre Boulez was known for being “in revolt against everything” — an atypical description for a composer and conductor of classical music, though an accurate description for a Frenchman. His bullish behavior led to his becoming one of the few paramount classicalists of our ongoing postwar period. In his youth, it was said that “his powerful aggressiveness was a sign of creative passion—a particular blend of intransigence and humor, the way his moods of affection and insolence succeeded one another—all these had drawn us near to him.”

In the early Seventies, Pierre Boulez had become infatuated with the works of impressionist pianist Maurice Ravel. The eccentricities of impressionism flavored his demeanor for a number of years. In New York, he had the seats torn-out of Avery Fisher Hall so he could perform a “rug concert” for his American fans. One of these concerts was followed by an after-party, hosted in an Upper West Side apartment for the elite members of the audience.

Attendees included Paul Simon and his then-wife Peggy Harper. They both had met Pierre Boulez a number of times—acquaintances, surely—but Pierre never seemed to remember their names. On this night, he again greeted the couple with confidence, believing Paul to be “Al” and his wife “Betty.” This was not the case, but Paul found the situation too humorous to upend. He finished the night as “Al,” and the peculiarity of the party stayed with him for fifteen years.

In Montauk, circa 1985, Paul recalled the memory and jotted it down on one of his legal yellow pads. Ideas grew around it, born of the midlife crisis he was trudging through, and he wrote: “A man walks down the street / He says why am I soft in the middle now / Why am I soft in the middle / The rest of my life is so hard.”

Paul began with the basic complaints of a man not unlike himself, and as the song goes on—much like a personal crisis—the thoughts become more abstract. “Got a short little span of attention / And woe my nights are so long / Where's my wife and family / What if I die here / Who'll be my role-model / Now that my role-model is / Gone, gone.”

“Because there's been a structure…those abstract images, they will come down and fall into one of the slots that the mind has already made up about the structure of the song.” “He ducked back down the alley / With some roly-poly little bat-faced girl / All along, along / There were incidents and accidents / There were hints and allegations…” And then came the chorus: “If you'll be my bodyguard / I can be your long lost pal / I can call you Betty / And Betty when you call me / You can call me Al.”

The studio’s synth player, Rob Mounsey, arranged a brief brass section that Roy Halee went to town with. “It was my idea,” he recalled. “However, it was Rob who wrote it down for the horns. It was his arrangement, and the groove that's going on in that song is Rob's groove. He played the groove in the verses, as well as the synth lines at the beginning and throughout the number, and it was that groove which turned the song into a monster, although the brass contributed quite a lot, too.”

Riding under the four trumpets and two trombones was a bass run by Bakithi Kumalo. Roy fed this line backwards, for the sake of experimentation, in the second half of the song. “I simply copied the line as originally played to a mono machine and then synced it backwards into the multitrack. That kind of thing was always happening… Anything to make it sound more interesting.” Morris Goldberg capped the tune off with a penny whistle solo.

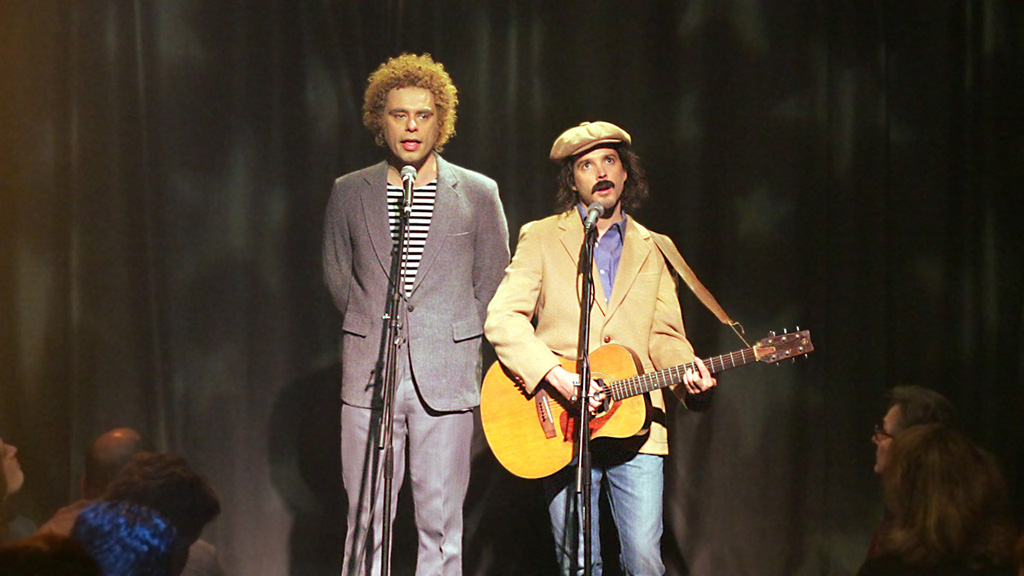

The music video intended to be released for “You Can Call Me Al” was a performance Paul gave while hosting “Saturday Night Live,” but he didn’t like it. Thankfully, Lorne Michaels had a better idea: in a small room, Paul Simon would lip-sync the song, and his good friend Chevy Chase would try his best to steal the spotlight. Chevy, at the time, was at the peak of his celebrity (though “National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation” was still three years away). The whimsical simplicity of the video earned it a heavy rotation on VH1.

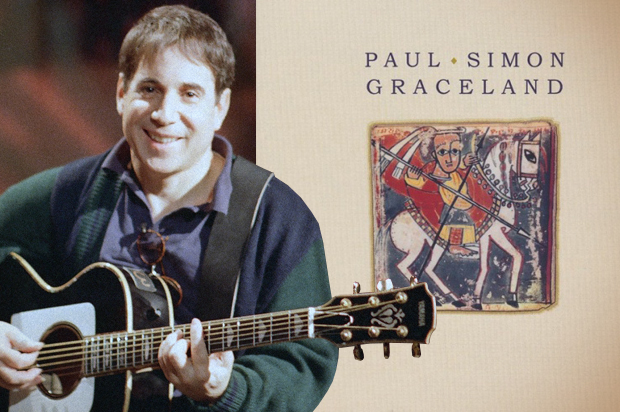

Released on September 5, 1986, “You Can Call Me Al” was the first single to introduce Paul Simon’s “Graceland” to the world. Its infectious, rooted rhythms shot it to #23 on the Hot 100, charting for twenty-nine straight weeks. Much of the MTV generation was introduced to Paul Simon by way of this song, featuring a goofy Chevy Chase mugging for the camera, and I challenge anyone old enough to remember music videos on television to keep from echoing these rhythms with non-lexical vocables. “Daa na na na! Daa na na na-na!”

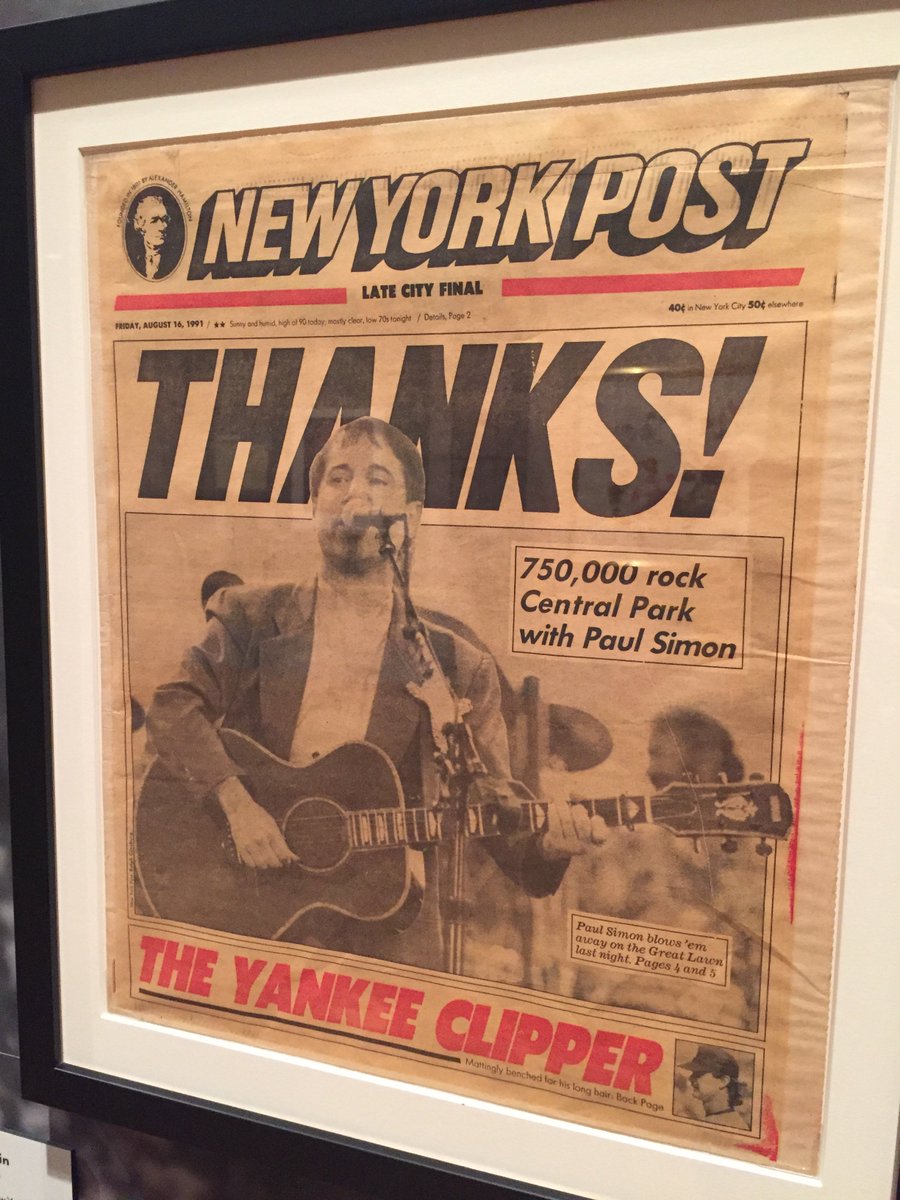

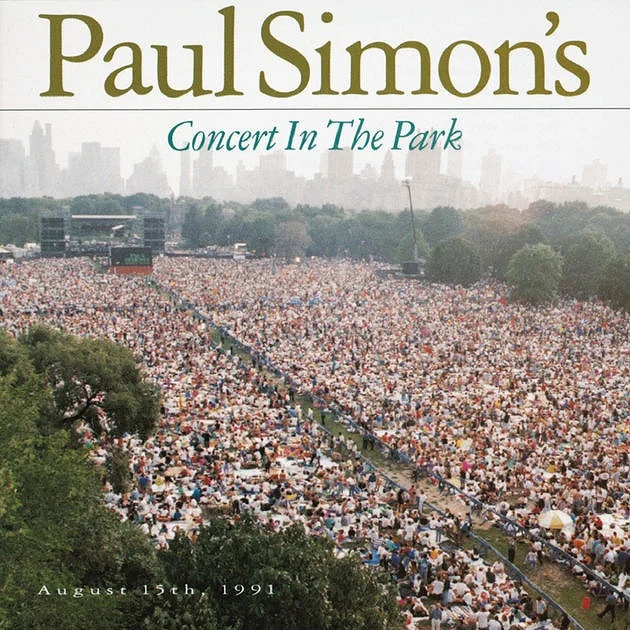

When Paul played Central Park again, in 1991, Chevy Chase made a surprise appearance during the break to join Paul in their famous ‘horn dance.’ That same year, Tennessean Senator Al Gore used “You Can Call Me Al” as his campaign song in seeking the Vice Presidential nomination from Bill Clinton. Gore went on to use “You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet” by Bachman-Turner Overdrive for his 2000 Presidential race, thereby institutionalizing the unsettling trend of every aspiring executive officer using a once-Top 40 pop song as a means of seeming relatable. Later selections included Van Halen, Bruce Springsteen, John Lennon, LeAnn Rimes, U2, CCR, the Rolling Stones, John Cougar Mellencamp, Boston, Celine Dion, Tom Petty, ABBA, Kid Rock, and Katy Perry. Paul Simon was one of the earliest and most recent contributors to this trend, lending “Bridge over Troubled Water” to George McGovern in ‘72 and “America” to Bernie Sanders in ‘16.

Once “Graceland” was finished in the mixing lab, Paul and Roy brought it to the executives at Warner Bros. They gave it a listen and returned with pockets full of doubt; not so much cynical but skeptical that an eclectic, African-inspired album like “Graceland” could be appealing. “Paul had tremendous faith in the record,” Roy recalled, “although I had my doubts, because it had been such a lengthy, difficult project, and the music was so different to what was on the charts. Those bass grooves just weren't happening at that time.”

“Just listen to ‘The Boy in the Bubble,’” the third single. “For me, the bass line and the feel of that tune is what the album is all about. It's the essence of everything that happened. The guitar, the drums, and that incredible bass add-up to a feel going-on at the bottom end that is unlike anything I've heard before or since. It's a major part of why the record was huge.” Masked by a jovial, accordion-led melody, “The Boy in the Bubble” muses on famine and terrorism—a daily occurance in most of the world—though the elite of western cultures are [by choice] largely oblivious. Paul said the lyrics were meant to blend “hope and dread,” adding, “That's the way I see the world: a balance between the two, but coming down on the side of hope.”

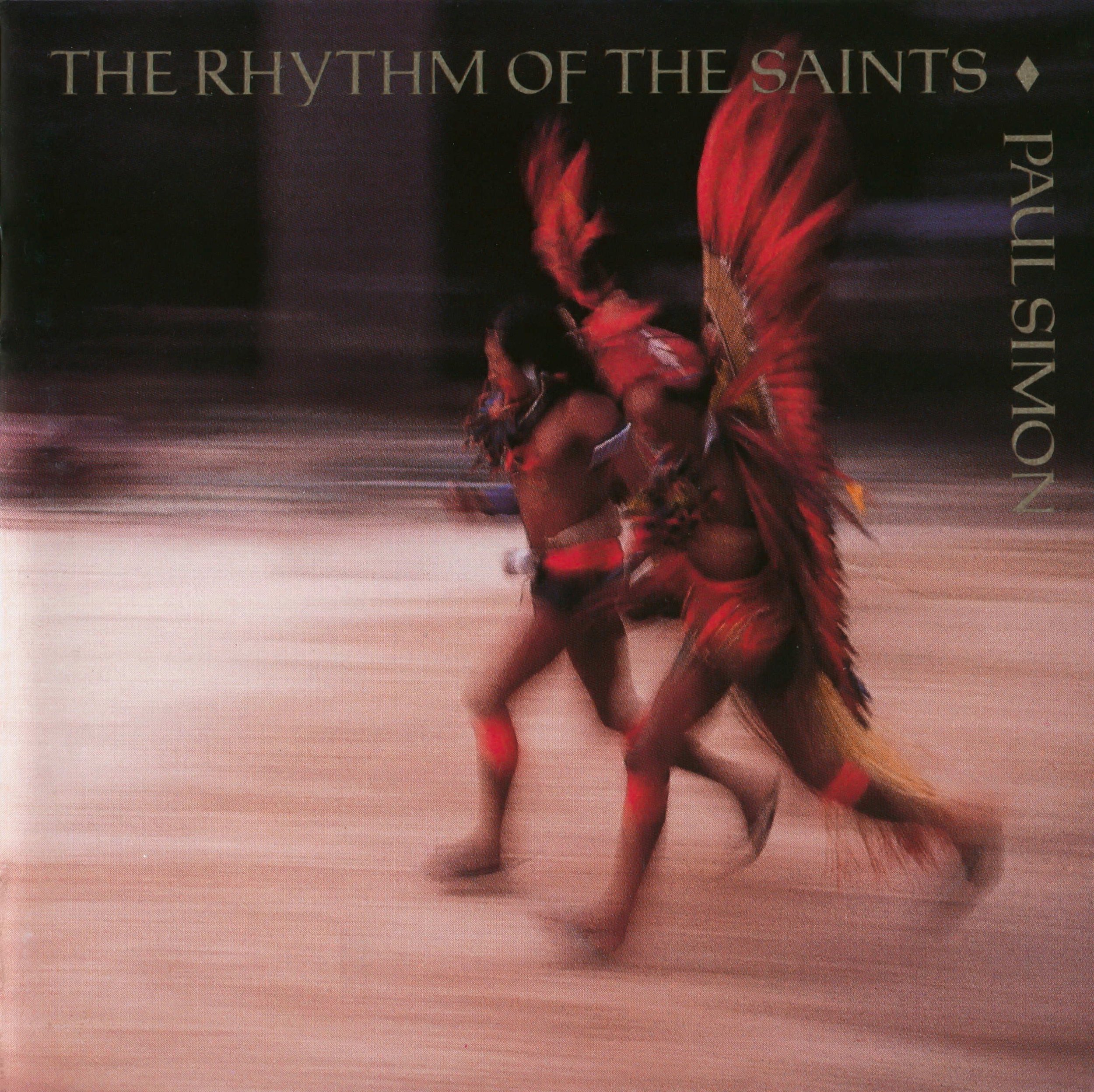

Beginning with “You Can Call Me Al,” each of the singles from Paul Simon’s seventh studio album increase in African affectation, ultimately turning 1987 into a milestone year; a year where postwar American society finally shifted away from majority conservatism to majority progressivism, opening the hearts and minds of millions to the idea that racial minorities are as cultured, capable, and compassionate as the average suburbanite.

In the fourth single, “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes,” a girl whose wealth affords her immeasurable freedoms and ease is contrasted with a boy whose poverty she cannot fathom. Featured singer Linda Ronstadt lends her earliest memory to the second verse of the fifth and final single, “Under African Skies,” while Joseph Shabalala of Ladysmith Black Mambazo lends his to the opening and closing verse. The somber chorus asks us to reflect on who we are: “This is the story of how we begin to remember / This is the powerful pulsing of love in the vein / After the dream of falling and calling your name out / These are the roots of rhythm and the roots of rhythm remain.” As Jeff Heller wrote, “The root of all rhythm—where our musicality as humans began—is from our heartbeat. That rhythm remains in songs to this day.”

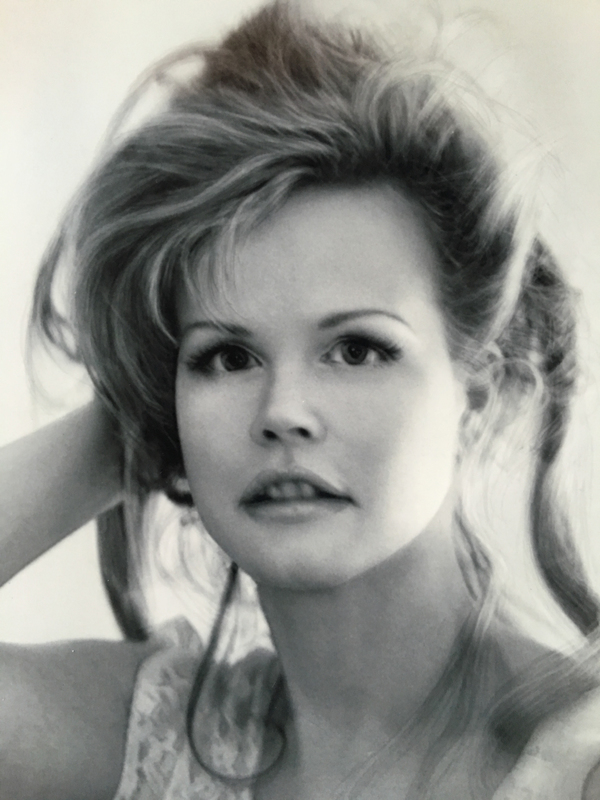

“Graceland,” the second single and title track, features The Everly Brothers on backing vocals (a dream-come-true for Paul Simon) singing of the misery and misfortune that plagues the protagonist’s mind as he drives south to find serenity. Spurred by his crumbling relationship with Carrie Fisher—which she confirmed as the inspiration—Paul wrote, “She comes back to tell me she's gone / As if I didn't know that / As if I didn't know my own bed / As if I'd never noticed / The way she brushed her hair from her forehead / And she said losing love / Is like a window in your heart / Everybody sees you're blown apart / Everybody sees the wind blow.”

Carrie Fisher said in her autobiography, “If you can get Paul Simon to write a song about you, do it, because he is so brilliant at it.” In a modern confessional, Claire Goldberg wrote of “Graceland” being “unapologetically happy—and yet it’s tinged with so much sadness… And it’s sad—there’s no doubt about it—but it’s so happy at the same time. It’s hopeful. ‘Graceland’ itself is a biblical place; a destination from a long journey, and somewhere where all his troubles will be absolved. It’s just one of the many songs on the album that is impossibly beautiful and filled with so many emotions that you can’t ever pick just one.”

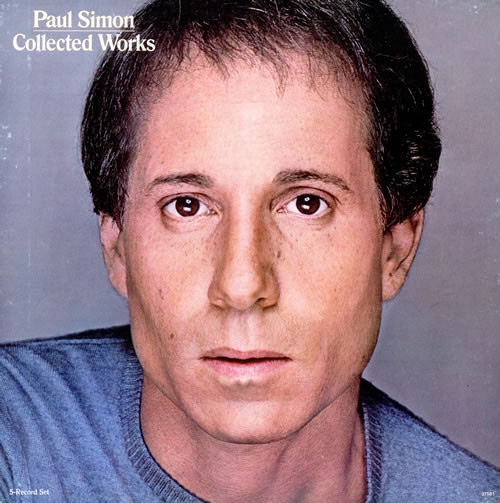

Despite the time, money, and resources Warner Bros. had poured into Paul’s African adventure, they did not believe “Graceland” would be a success. Paul’s previous two albums had been failures; he had become a “has-been;” acquiring him from Columbia was a “bad investment.” They wanted to focus on booming artists, like Madonna, and Prince. “It could be that I've reached the point in my career where I can't be a viable commercial force in popular music,” Paul mused, stewing in self-criticism as Warner Bros. deflated his excitement.

“Graceland” was too eclectic and foreign; the unorthodox amalgamation of pop, rock, zydeco, a cappella, isicathamiya, mbube, and mbaqanga was too niche; too “crazy.” Furthermore the tracks rise and fall in emotion, “As in a play,” Paul explained, “the mood should keep changing.” Then there was the cover art: an obscure 16th century painting of a ‘Christian icon’ from Ethiopia, photographed at the Peabody Essex Museum.

As Stephen Holden wrote, following its August 1986 release, “‘Graceland’ opens with a montage of jarring lyrical images that describe a terrorist bombing, drought, and famine; bizarre new medical technology and lasers in the jungle. Set against a slogging rhythm of accordion, bass, and drums, Mr. Simon's stark telegraphic poetry rings with a mixture of alarm and harsh exhilaration… which conjures an indelible picture of the world as a global village, at once united and divided by the magic of technology.” Ethan Zuckerman called this introduction to “Graceland” “an excellent metaphor for anyone confronting our strange, connected world,” adding, “At its best, Graceland sounds as if Simon is encountering forces too large for him to understand or control. He’s riding on top of them, offering free-form reflections on a world that’s vastly more complicated and colorful than the narrow places he and Art Garfunkel explored in their close harmonies.”

“‘Graceland,’” Stephen Holden extolled, “is something new; an album that thoroughly blends various styles of acoustic black South African folk music with strains of stylistically related American rock-and-roll into songs that have unusual shapes and structures, and that sound unlike anything familiar to most American ears. That is because about half the album was recorded in Johannesburg with many of the finest black South African musicians playing music that only later was shaped into songs.” “With his characteristic refinement, Mr. Simon has fashioned that event into the rock album equivalent of a work of literature.”

Robert Christgau of The Village Voice praised “Graceland,” calling it Paul’s greatest work since his eponymous album of fourteen years prior. Patrick Humphries of The BBC said “Graceland” “may well stand as the pinnacle of his remarkable half-century career…” The Independent called it “complex, ebullient, and life-affirming—and, in yoking this intricate dance music to his sophisticated New Yorker sensibility, Simon created a transatlantic bridge that neither pandered to nor patronized either culture.” From this moment on, wrote William Ruhlmann of AllMusic, “‘Graceland’ became the standard against which subsequent musical experiments by major artists were measured.”

Rolling Stone wrote, in a recollection of the album, “The robust bounce and soulful melodicism of township jive, which gave Simon's brainy lyricism a rhythmic kick in his recent work, has become a daily soundtrack in urban yuppie condos and suburban living rooms and on radio airwaves from Australia to Zimbabwe.” The New York Times identified “Graceland” as the album that made African rhythms popular in the western world, for the remainder of the Eighties and much of the Nineties.

“Graceland” became Paul Simon's most critically-acclaimed and commercially-successful solo album, peaking at #3 on the Billboard Albums Chart, certified 5x Platinum by the RIAA, and on to sell over sixteen million copies. It received 5/5 star-ratings across the board, from the likes of AllMusic, American Songwriter, Pitchfork, and Rolling Stone, in addition to winning the Grammy for ‘Album of the Year’ with its title track taking ‘Record of the Year’ in 1987.

“Graceland was never just a collection of songs, after all,” wrote Andrew Leahey of American Songwriter. “It was a bridge between cultures, genres, and continents, not to mention a global launching pad for the musicians whose popularity been suppressed under South Africa's white-run apartheid rule.” Paul was “ahead of his time,” and though later groups would receive flak for too-closely taking inspiration from “Graceland,” Paul tended to defend the artists; in one instance, he said, “In a way, we were on the same pursuit… I don't think you're lifting from me, and—anyway—you're welcome to it, because everybody's lifting all the time. That's the way music grows and is shaped.”

As Ethan Zuckerman once wrote, “Collaborations like ‘Graceland’ don’t happen without the participation of two important types of people: xenophiles and bridge figures. Xenophiles, lovers of the unfamiliar, are people who find inspiration and creative energy in the vast diversity of the world.” Xenophiles, like Paul Simon, “move beyond an initial fascination with a cultural artifact to make lasting and meaningful connections with the people who produced the artifact.” And then there are “bridge figures [who] straddle the borders between cultures, figuratively keeping one foot in each world. Hilton Rosenthal was able to broker a working relationship between a white American songwriter and dozens of black South African musicians during some of the most violent and tense moments of the struggle against apartheid. As a bridge, Rosenthal was an interpreter between cultures and an individual both groups could trust and identify with…”

In 2012, Rolling Stone named “Graceland” the 71st Greatest Album of All Time, calling it “an album about isolation and redemption that transcended ‘world music’ to become the whole world's soundtrack.” According to Paul, “What was unusual about ‘Graceland’ is that it was on the surface apolitical, but what it represented was the essence of the anti-apartheid in that it was a collaboration between blacks and whites to make music that people everywhere enjoyed. It was completely the opposite from what the apartheid regime said, which is that one group of people were inferior. Here, there were no inferiors or superiors; just an acknowledgement of everybody's work as a musician. It was a powerful statement.”

Among the affected were young, white suburbanites, on to become more open-minded than their predecessors. Claire Goldberg was one such young American: “The first Paul Simon album I listened to was ‘Graceland,’ of course. I had heard the classics before, including ‘The Sound of Silence’ from his Simon & Garfunkel days… but ‘Graceland’ was the first piece of Paul Simon that started to mean something to me… That album reminds me of so many things; of all the road trips I’ve ever taken, of my parents, of home, and—strangely enough—it reminds me of somewhere I’ve never even been before. With the African melodies that Simon infuses in his Americana music, it reminds me of places far away and of every corner of this country that I call home…”

While Paul was in South Africa, rejecting apartheid and blowing the roof off of pop music conventions, Art Garfunkel was in Nebraska, walking. He was comfortable—for the moment—with his anonymity, which he pretended was by choice. He had not spoken to his old friend in more than two years; Paul had since been clambering to get back on top, and Art was taking it easy. All he had done since the Concert in Central Park was walk west — that, of course, and the movie “Good to Go.”

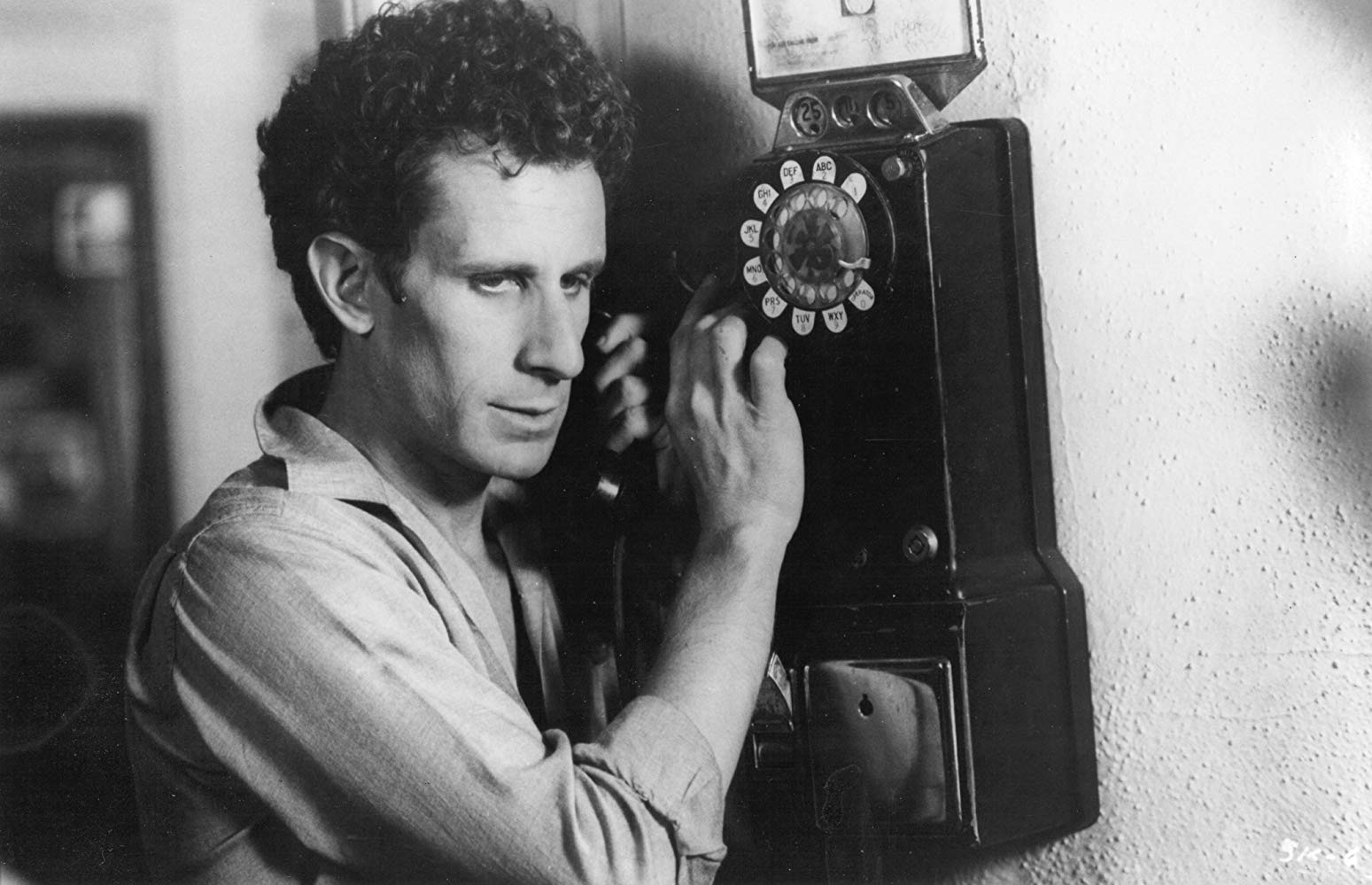

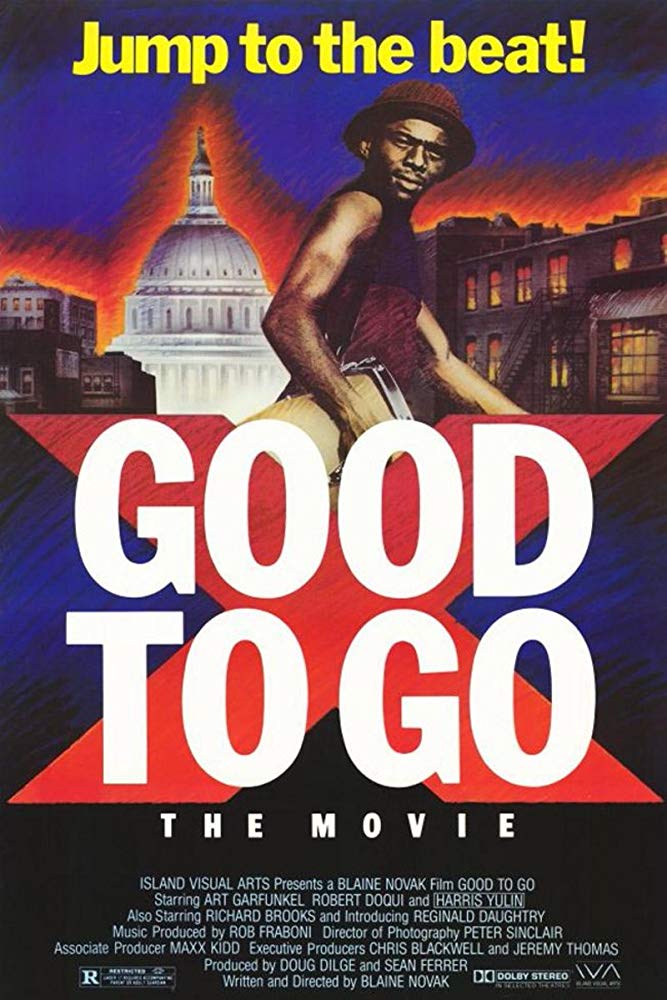

Released three weeks before “Graceland,” “Good to Go” showcased Art Garfunkel as beat journalist S.D. Blass, rummaging around Washington DC for ‘the next big story.’ After hearing about a nurse that was recently raped and murdered, he dives ass-first into the underground go-go music scene, eventually publishing the article “Nurse Murdered at Go-Go: Music and Drugs Blamed for Violence,” and then the movie spends the majority of its runtime in back alleys and go-go dance halls.

“Good to Go” was an attempt by the DC-area’s go-go music scene producers to make go-go music into a big deal. I don’t need to ask if you know how that turned out because I know you know it didn’t. Go-go impresario Maxx Kidd and three other go-go producers poured $1,500,000 into a script written by a guy with suboptimal credentials: co-writer of a “madcap caper” about “a team of detectives who are following, and are being followed by, a group of beautiful women;” co-writer and star in a cliché 1980s Hollywood story comparable to films about sexual androids, your weird uncle’s nightclub, Helen Mirren’s “Hussy,” prostitute hijinks, sailor hijinks, and something called “Slayground” with the tagline “Welcome to your funeral;” and then a minor role as “Capt. Braverman” in the sophomoric 1984 raunch comedy “Up the Creek.”

Critic Lars Skogan summarized “Up the Creek” as the story of “four losers” (“Bob the slacker, Irwin the alcoholic geek, Gonzer the human food disposal, and Max the ne'er-do-well”) who are “forced and bribed to represent their university in an intercollegiate raft race,” with foes including “a whole team of marines, and preppy Ivy-leaguers determined to win.” “Up the Creek” was written by the guy who went on to pen 1998’s “Rush Hour” and 2004’s “National Treasure,” which I must admit is one of my favorite movies.

The early Eighties were a different time, evidently, and Americans had demanded more “Animal House” than “Anchorman,” with comedic lines such as Gonzer’s “I risked my life, and you give me Light Beer?” The writer put the onus of the film’s disappointing performance on the director, saying he “was not a great comedy director; he missed a lot of jokes,” but methinks the writer did, too. In her review for the Washington Post, Rita Kempley called it “a moist smut movie,” “headed for the whitewater vapids,” adding, “The only thing good about this movie is Chuck, played by Jake the Wonder Dog—a talented and charismatic Spaniel with a lovely shaggy mane and a divine bark. Chuck has all the best scenes. Still, that brave little pooch is ‘Up the Creek’ without a dog paddle. UP THE CREEK — At area theaters, in English and Spaniel.”

The leader of the “whole team of marines,” Capt. Braverman, was portrayed by Blaine Novak, the Garfunkelish cross between Ted Danson and a garden gnome. His signature line, “A commander couldn’t ask for better soldiers,” is immediately followed in the trailer by a shot that would hilariously argue otherwise! One reviewer, in 2001, wrote, “Is this flick good? Jesus, no. Is this flick funny? Somehow, yes… ‘Up the Creek’ has not aged well (what a shocker) but it's a perfect example of the pointless, disposable comedies they made in the early- to mid-Eighties… Every scene, every joke, every character here is dumb—and thank God… I think ‘Up The Creek’ was made specifically FOR drunk people (and possibly BY drunk people) but that's okay; it's all good. I mean, the film's not good, but then again, it is. Ah, forget it. Just grab a case, a beer bong, and watch the damn thing.”

After losing the camo fatigues, Blaine Novak went home and fulfilled a contract with go-go impresario Maxx Kidd, penning “Good to Go,” a real “snoozer” of a film. “The cover made it look like a decent action flick,” wrote one reviewer. “However, it moves at a snail's pace and had no intelligible plot whatsoever. I feel it was a showcase for the ‘go-go’ music contained within and nothing else.” One of IMDb’s most prolific reviewers agreed, saying that, although the first 75 minutes are “slow moving at first,” the plot “really picks up in the last fifteen minutes” as Art Garfunkel’s S.D. Blass evades “the murderous Harrigan, who's trying to prevent him from telling the truth about his cold-blooded murder of Tony.” Blass is simultaneously “trying to prevent a major race-riot from erupting in the streets of DC” and so he mounts the stage of a televised go-go concert, “telling the millions of viewers the truth,” thereby “vindicating himself…to the wild cheers of thousands of go-go music fans…”

Though most of the $1,500,000 budget came from Maxx Kidd’s own pocket, a portion of the budget was provided through an advertising deal with Pepsi. There’s so much product placement that “It's practically a ninety-minute commercial for Pepsi,” which is odd considering all the “drug-fuelled rape and murder.” The headline for the film’s only somewhat-complimenting review read “Witness Art put the ‘funk’ in ‘Garfunkel’ and watch this oddity today!” Even with his enthusiasm for the singer, the reviewer could not fathom why they chose “noted badass Art Garfunkel” for the lead role, given that Art has the charisma of “a wet noodle.”

To the chagrin of Maxx Kidd, “Good to Go” did not make back its budget. Its failure roots to the bones of the film: conceived to popularise a musical subgenre rather than to tell a story. This was evident in its trailer, which devotes over eighty percent of its runtime to footage of the band Trouble Funk playing the theme song, and a crowd of people dancing. A pulsating red X overlaid by the film’s title took another five percent, leaving the rest of the trailer to hurl shots of chases, car crashes, and fire, with a single half-second shot of Art Garfunkel’s protagonist turning to run—and, for the unfamiliar, you’d have never recognized him in the dark, nor would his appearance have made any sense, considering how no part of the trailer indicated a narrative of any sort. The trailer said more about the film than the film, as it was a film made for the music — and when you make a film not for the sake of a film, you fail to make a film, and thus your film will fail to make money.

Maxx Kidd had been the shepherd of go-go music ever since funk guitarist Chuck Brown birthed the subgenre in the mid-Seventies. It developed a unique regional style in the afro-urban Washington DC area, blending funk riffs, R&B bass, and early hip-hop beats into a riotous “sultry stank.” The key component, however, was the standard dancehall requirement of call-and-response with a live audience, which popularised the go-go subgenre among the nightclub scene. By the mid-Eighties, wrote Natalie Hopkinson, “the music’s relationship to Washington DC was roughly analogous to hip-hop’s relationship with the Bronx.”

As one of America’s most inquisitive cultural scholars, Hopkinson mused, “the question I’m most commonly asked is, Why did go-go stay in DC?” Well, the record label behind Bob Marley’s rise to power had produced a film in 1972, “The Harder They Come,” to boost the reputation of reggae music—and it worked. Maxx Kidd tried to do the same with go-go music, signing the same label executive from “The Harder They Come” to help produce “Good to Go.” That executive was Chris Blackwell, “a white, Jamaican-born, UK-educated music aficionado.”

Blackwell never felt comfortable in black crowds. For the shoot, he arrived in Washington DC with a fleet of bodyguards. Halfway through filming the movie, he fired director Don Letts—a black man—and allowed the writer—the snow-white Blaine Novak—to finish the film. Novak had never directed before, especially on such a large production, and he had no understanding of black culture or the afro-urban Washington DC area. The script he wrote was based on stereotypes, newspaper headlines, and common misconceptions. For a film about a black-helmed subgenre of music in a black community, meant for a black audience, there was a surprising and utter lack of consideration for authentically portraying black culture.

On of the film’s co-producers said of the go-go music scene, during filming, “We heard it’s a bunch of kids stoned on PCP dancing around… When the music stops, fights break out. If you’re white, you don’t go into these scenes because you’re in an incredibly dangerous situation.” Though Maxx Kidd had put his hopes in his team, Chris Blackwell and Blaine Novak could only muster an aura of “racist paternalism,” whether subconsciously or not, which only stood to enrage an already-disrespected afro-urban Washington DC.

Kip Lornell and Charles Stephenson Jr., authors of “The Beat: Go-Go Music,” wrote of the producers vying to conjure “a highly volatile mixture of street violence and niggers crazy on drugs, all highlighted by the blackest music outside of Lagos, Nigeria… It was beginning to look like the ‘70s, when blaxploitation films like ‘Shaft’ and ‘Cotton Comes to Harlem’ were commonplace. If only [Blackwell] had aimed so high!”

Meanwhile Don Letts suggested that “go-go did not translate well into film” since “there is something about it that is intangible. It is almost too hot for vinyl and definitely too hot for celluloid.” “Go-go was the ultimate black tribal rebel sound in Washington, home of the White House and the capital of America. People tried to demonize the whole scene, [but] the bottom line is: you don’t know the complete story of contemporary black music if you don’t know go-go.”

The soundtrack for “Good to Go” launched the same day as the film, in August 1986, with thirteen songs from local go-go bands. The lead track, “Good to Go,” was supplied by Trouble Funk, who had helped raise and foster the go-go scene. Their first studio record, 1982’s “Drop the Bomb,” was highly praised by critics—among them, Robert Christgau and Rolling Stone. The record produced one titular and two booming singles—“Pump Me Up,” “Drop the Bomb,” “Hey Fellas”—on to quickly become go-to samples for hip-hop’s earliest deejays. First scratched and cut by the likes of Public Enemy (“Fight The Power”) and M.A.R.R.S. (“Pump Up The Volume”), Trouble Funk’s go-go influence continues to bare descendants, as in Joe Budden’s 2003 hip-hop hit “Pump It Up.”

Go-go music never went national, though it still thrives in Washington DC. “Good to Go” made no waves, and Maxx Kidd pulled it from theaters shortly after its release. It was repackaged as “Short Fuse” and released again on VHS, though the film is no longer in print. The father of go-go died in 2017, in his suburban-DC home, at the age of 75.

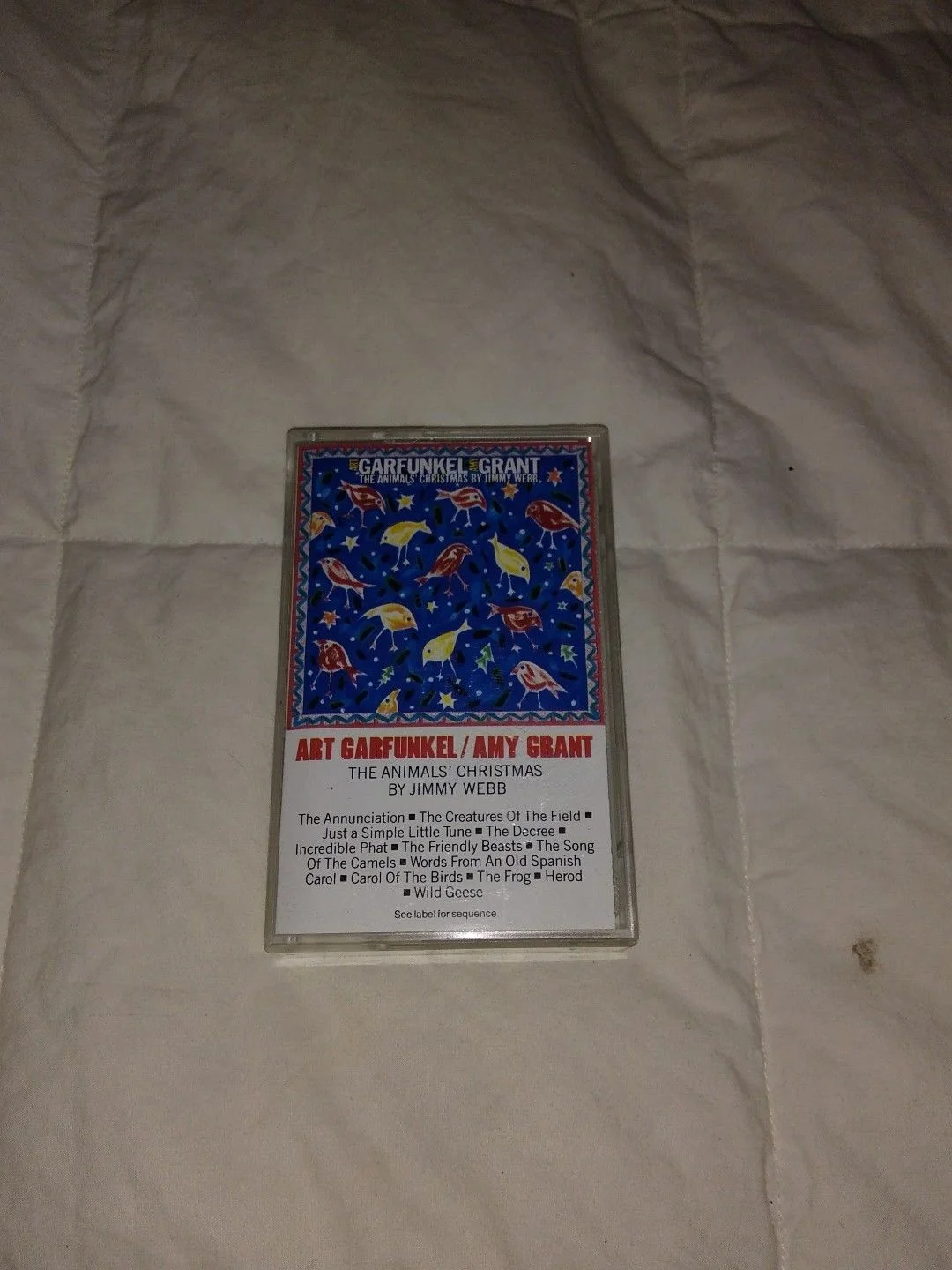

“In ‘83, my friend Jimmy Webb showed me a piece he was writing—a cantata for a children's choir and small orchestra for his local church in Tuxedo, New York—and, it being a noncommercial endeavor, I was particularly interested in it,” Art wrote, in his first poetry collection, “Still Water,” “because I had become cynical about the fact that the record business will professionalize one's musical attempts in a way that can hurt them. And I followed Jimmy's rehearsals in Tuxedo and…I told him I wanted to get involved. By the next year, he had written an extension, doubled its length, and wrote various sections for me as solo singer, narrator, and the angel Gabriel.”

“Good to Go” didn't do Art any favors; its failure boxed him out of any chance at another big Hollywood film. (Being B-listed is one thing; being in a B-list bomb is another.) So Art returned to music, setting his sights on redemption.

“We all performed [Webb's cantata] with orchestra; children's choir—boy singer, girl singer—at St. John the Divine Cathedral in New York… We made a live recording of the shows, which later seemed to me too loose, so we planned to record it in the studio…”

Art wanted Roy Halee to come in and oversee the production of this Christmas album, but Roy was still knee-deep in “Graceland,” hashing tracks with Paul Simon. Art waited, and waited, all the while blaming Paul for holding their shared engineer hostage.

Aggravation bloomed into anger. The clock was ticking, and Art didn't want to delay his album any further. With Christmastime arguably being the best time to release, he moved-on without Roy, deciding he and Jimmy Webb would manage the recording themselves.

“I had it finished by Christmas of ‘86, which I gather is when it came out. It's a gothic cathedral of an album; it's very ambitious. It was the type of project that would have been done by papal commission long ago.”

It was a retelling of the Nativity story—the birth of Jesus Christ—from the perspectives of animals. Art portrayed the angel Gabriel and Amy Grant played the Virgin Mary, performing in the operatic ‘recitative’ form, also known as “Sprechgesang” or “sing-talking.” Listening to all forty minutes of “The Animals’ Christmas” is like boarding a soft-top airplane and gliding at highway speeds through clouds of ennui—listless boredom and emptiness—while someone plays a saxophone from inside a baby grand piano. (Sometimes research is not fun.)

Columbia released “The Animals’ Christmas” on the last day of the year, 1985. It received one critical review: nine out of ten stars from AllMusic’s Joe Viglione. He described it as “one of the best Christmas albums of the Eighties,” calling it “good brain-food for grownups and children alike.” “On the upside for consumers,” he wrote, “none of these tunes are familiar ‘Christmas classics’ hammered into the consciousness during the holidays. The church-like feel of the project keeps [its songs] from being able to break-out on seasonal radio next to tracks from Phil Spector's Christmas Album, Brenda Lee, Bing Crosby, and the other perennials who show up on the airwaves around Thanksgiving time and beyond,” which is nearly the most un-American thing I’ve ever heard. (Somebody dig-up Joe McCarthy; he’ll have a ball.)

Art spent the warm months of 1986 walking. In September, his father died—Jack, the former traveling salesman—and he sank once again into depression.

Paul was on top of the world. He was 45 years old—or, like a hot mommy would say, 45 years young—and had just won the two most sought-after Grammy Awards, back-to-back. His subsequent “Graceland Tour” was selling-out across the country, in magnitudes he hadn't seen since he was shackled to Art Garfunkel.

“Once you go away for a bit,” he said, “you wonder who people think you are. If they don't know what you're up to, they just go by your history. I'm so often described as this person that went to other cultures—which is true—but I never thought of it that way… I wondered, ‘Is this an appropriate context to express various thoughts, given the way people listen now and the way music is exposed to the world?’ Pop music, as it's constantly evolving, is completely different from the value system and aesthetic I grew up with and contributed to.”

Half of his concerts were videotaped, to be released as music videos, and album sales remained steady even two years after release. Commercial success filled his pockets, and cultural celebrity filled his heart, but both paled in comparison to the respect and adoration of thousands of grateful fans, singing along between the low edge of the stage and the back row of the balconies.

“Finishing a song is more satisfying now because I'm grateful, whereas when I was twenty-eight, I expected it. Now if I find something to say, and I say it in a way that I think is artful and true, I'm relieved I wasn't frustrated or stymied. When I was younger, I just said whatever I had to say. I ask myself now: Do I deeply believe that? Will anybody get it? Am I just talking to myself? You have to put that aside because it's not very helpful.”

“I'm trying to be as honest as I can, expressing myself musically and lyrically—editing-out what might be considered obscure, but not trying to oversimplify or be condescending—and then I have to let go, even if I don't immediately understand the words. What I meant eventually reveals itself. You can be too familiar with the process, which I've been doing since I was fifteen. Sometimes, instead of manipulating the craft, you have to just be the vessel through which some sort of inspiration will flow.”

In 2007, “Graceland” became the second of his works to be selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Recording Registry, due to its being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically important.”

Upon receiving his medical license, in 1971, Irwin Redlener moved to Arkansas to practice pediatrics. There, he met his wife, Karen. In the early morning of February 4, 1976, a 7.5-magnitude earthquake struck Guatemala, leveling half of its capital city. Poorly-built concrete and adobe homes collapsed across the country, and in neighboring Honduras, crushing and killing over 23,000 people while leaving an additional one million without homes.

The US Air Force responded with shipments of medical supplies and food. Hundreds of doctors flew to Guatemala, where hospitals were overflowing with casualties; the city itself had become a trauma ward. The US military erected field hospitals nearby, to be serviced by America’s volunteer doctors. Among them was Dr. Irwin Redlener, stationed in a rural village between two jungle-encrusted mountains. His focus was on the children, for whom he treated infections, reset bones, stitched wounds, and at one point was held at gunpoint by a frustrated teen.

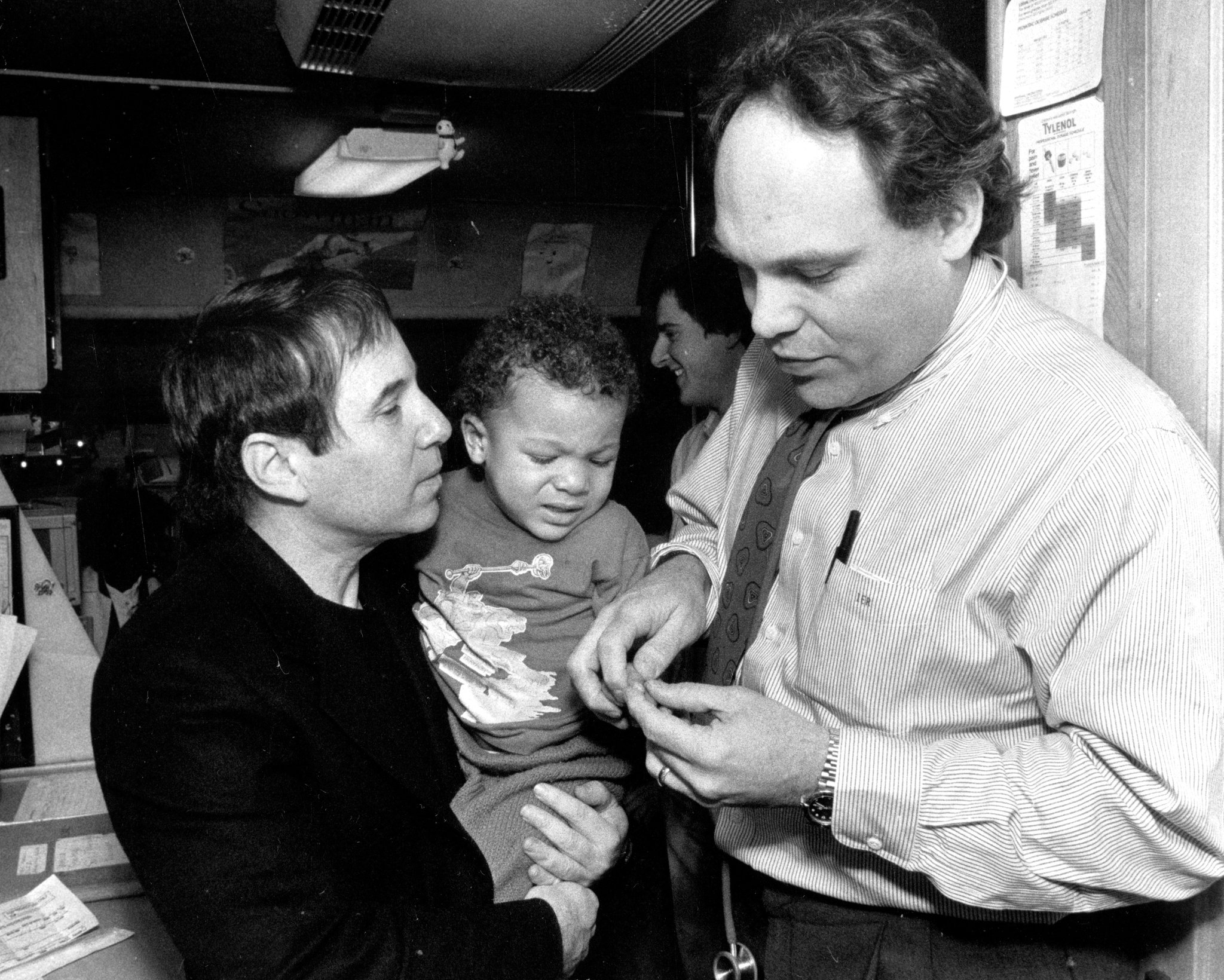

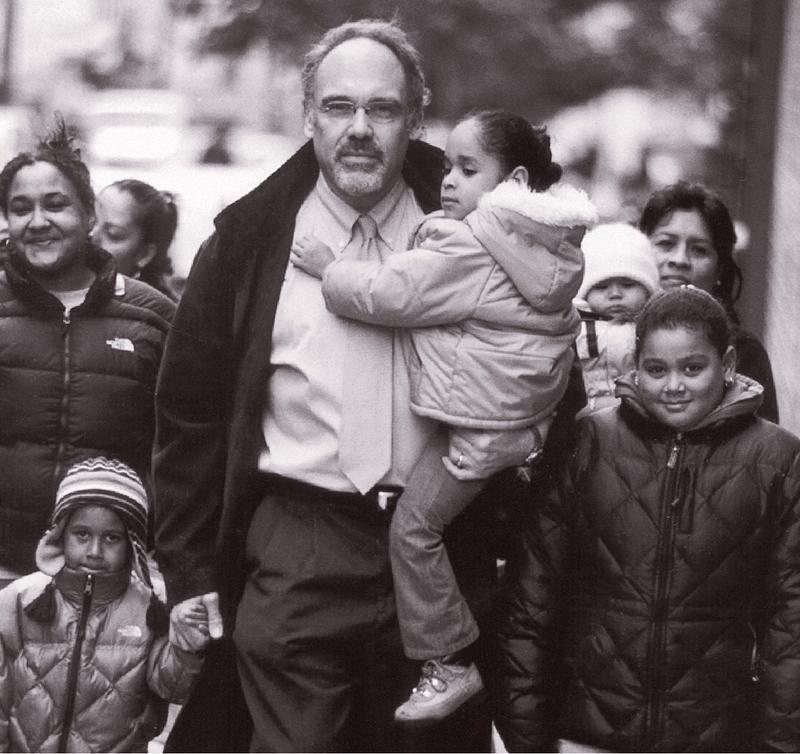

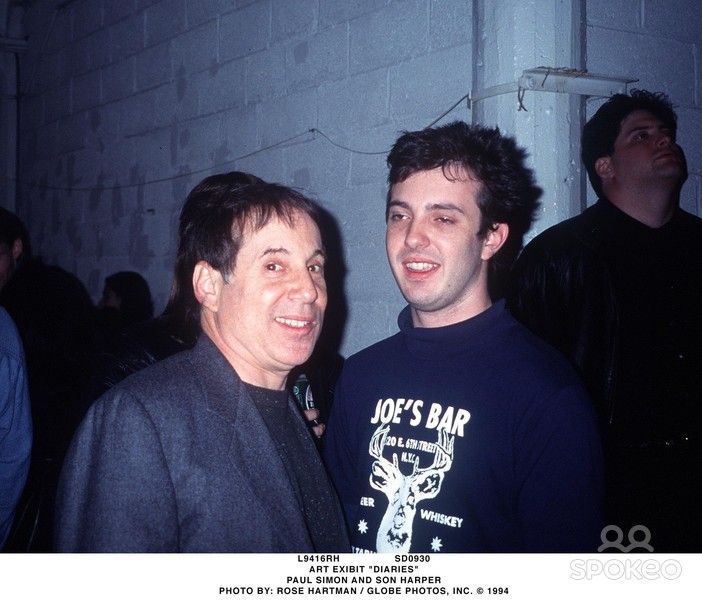

After a few weeks of pro bono aid, Dr. Redlener returned to America and opened a Child Action Center, to counsel and heal abused children. He became a member of the Physicians for Social Responsibility and, in 1985, he joined the board of ‘USA for Africa’ as its director of medicine and grants. There, he met Paul Simon, during the recording of “We Are the World,” and the two quickly bonded over their shared heritage: Redlener, a native of Brooklyn, and Paul, a boy from Queens. The latter suggested they collaborate in an effort to remedy homelessness in their city.

The two toured shelters and welfare hotels across Manhattan and Long Island. “We were speechless,” said Redlener, recalling a particular tenement at 32nd and Broadway, “it was a horrible, squalid old building, absolutely teeming with poor children and their families… There were kids and moms everywhere.” “They would have a hot plate—no stoves; a bath that was used to wash clothes.” “It was a hellhole. We both had the same feeling: Where the hell am I?”

This scene burned itself into their hearts, forging within them an indefatigable resolve to combat the sordid, sorry slums of their hometown. “There was something—I don't know how to describe it other than absolutely compelling and romantic—about this vision of somebody going to a place, obviously in need, and practicing what they had learned to do.”

In 1987, the unlikely pair founded the Children's Health Fund — a nonprofit organization of mobile medical clinics designated to provide healthcare for the homeless and impoverished children of New York City. The CHF began with a single refurbished van, designed by Redlener's wife, Karen, and paid for by Paul Simon. “We have basically taken the entire pediatric office and put it on wheels, so we can take it with us,” said Redlener, beaming. “It's like a highly-mechanized, highly-developed house call.”